Journal of Oral Biology

Download PDF

Case Report

*Address for Correspondence: Mario D. Ramos, Assistant Professor, College of Dental Medicine-Illinois, Midwestern University, 555 31st St, Downers Grove, IL, 60515, USA, Tel: 630-515-7493; Fax: 630-515-7290; E-mail: velliyka@sdm.rutgers.edu

Citation: Ramos MD, Aldahlawi A, Gonzalez C. A Technique to Improve an Ailing Interim Implant-Supported Fixed Partial Denture. J Oral Bio.2015;2(2): 3.

Copyright © 2015 Velliyagounder et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Oral Biology | ISSN: 2377-987X | Volume: 2, Issue: 2

Submission: 01 August 2015 | Accepted: 04 September 2015 | Published: 07 September 2015

Prior to removal of the ailing interim FPD, diagnostic impressions were taken using fast set alginate impression material (Jeltrate, Dentsply Caulk, Milford, DE); face-bow registration and occlusal records (Regisil, Dentsply Caulk, Milford, DE) were also obtained. Diagnostic casts already mounted on a semi-adjustable articulator (Whip Mix, Louisville, KY), were duplicated. A wax-up of the objective area was made using the duplicated model (Figure 2).

The area of the lower anterior incisors as well as 15 mm below were demarcated and posteriorly grinded out on the model (Figure 3), using a Mio Motor (NSK Dental LLC, Hoffman States, IL) with carbide burs. Space was created to allow placement of the implant replicas (Dentsply Implants, Waltham, MA).

Clinically, the provisional abutments (Dentsply Implants, Waltham, MA) and interim FPD were retrieved; periimplant tissue was examined on the implant sites and deemed within normal limits. Copious irrigation using digluconate chlorhexidine (Peridex, 3M, St. Paul, MN) on a plastic syringe was made, to remove plaque and debris from the area. Implant impression copings (Dentsply Implants, Waltham, MA) were adequately screwed on both implants manually. Dental floss (Oral-B Essential floss, Procter and Gamble, Cincinnati, OH) was tied between the implant impression copings, followed by an application of pattern resin (Duralay, Reliance Dental Mfg. Co., Worth, IL) extended towards the incisal edges and occlusal surfaces of adjacent teeth (Figure 4). Subsequently, the implant impression coping-pattern resin unit was carried out intraorally.

On the laboratory, implant replicas were screwed to their respective implant impression copings and subsequently positioned on the model using dental stone (Microstone, Whip Mix, Louisville, KY) (Figure 5A). The implant impression coping-pattern resin unit was unscrewed from the implant replicas (Figure 5B). A new set of a screw-retained interim FPD was built using metallic provisional abutments (Dentsply Implants, Waltham, MA) in conjunction with an indirect technique and acrylic resin (Jet, Lang, Wheeling, IL).

A Technique to Improve an Ailing Interim Implant-Supported Fixed Partial Denture

Mario D. Ramos1*, Abdulelah Aldahlawi2 and Cesar Gonzalez2

- 1College of Dental Medicine-Illinois, Midwestern University, Downers Grove, IL, USA

- 2Department of Cariology and Restorative Dentistry NovaSoutheastern University College of Dental Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA

*Address for Correspondence: Mario D. Ramos, Assistant Professor, College of Dental Medicine-Illinois, Midwestern University, 555 31st St, Downers Grove, IL, 60515, USA, Tel: 630-515-7493; Fax: 630-515-7290; E-mail: velliyka@sdm.rutgers.edu

Citation: Ramos MD, Aldahlawi A, Gonzalez C. A Technique to Improve an Ailing Interim Implant-Supported Fixed Partial Denture. J Oral Bio.2015;2(2): 3.

Copyright © 2015 Velliyagounder et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Oral Biology | ISSN: 2377-987X | Volume: 2, Issue: 2

Submission: 01 August 2015 | Accepted: 04 September 2015 | Published: 07 September 2015

Abstract

Objective: Implant-supported interim prostheses aims to preserve the natural periodontal architecture, protect the surrounding tissues, and provide patients with immediate esthetic and functional outcomes. The objective of this clinical technique article is to present a reliable method to replace an ailing interim implant-supported fixed partial denture (FPD).Clinical considerations: Patient presented with an ailing interim implant-supported fixed partial denture (FPD) replacing all lower anterior incisors. After case was clinically and radiographically evaluated, diagnostic casts were mounted. Once the interim FPD was retrieved, provisional abutments were dislodged and cleaned. Implant impression copings were carried out intraorally using pattern resin; its respective implant replicas were attached and screwed. Healing abutments were hand-screwed to keep the periimplant tissue architecture until the delivering of the newly fabricated interim FPD. The implant impression copings and its respective implant replicas were positioned on the diagnostic cast using dental stone. The two provisional abutments were positioned on the implant replicas and screwed in place for the relining of the new interim prosthesis previously made with acrylic resin. The new interim FPD was finished, polished and delivered.

Conclusion: This clinical technique presents a reliable method for fabricating an immediate interim implant-supported FPD to replace an existing ailing interim prosthesis.

Introduction

A great dental educator once wrote: Provisional restorations are the blueprint for success [1] such principle should be indeed applied to implants prostheses undoubtedly. Pjetursson and colleagues, by comparing survival and complications rates from studies published before and after the year 2000 (from 1994 to 2012), concluded that dentistry shows a continuous positive learning curve in dental implants: the 5-year survival rate of implant-supported prostheses significantly increased in newer studies (97.1%) compared with older studies (93.5%) [2]. On the contrary, there was a significant increase in the number of technical complications for the overall results. It might be that lack of attention to the provisional stage could have a negative impact on the predictability of our implant treatment. Thus, the significance of the provisional stage on implant dentistry cannot be overstated [3].The use of implant-supported interim prosthesis on partially edentulous patients aims to confirm the initial diagnostic restorative design [1,4-7], implement acceptable esthetics [1,4,5,8], phonetics [7], comfort and function [7-9]. Potentially, it facilitates a clear and objective communication between patient, dentist and technician [1,10-13]; improves the periimplant conditions [1,7,10,14,15]; and assess proposed occlusal schemes before definitive restoration is placed [9].

Provisional restorations designs appertain to implant therapy range from the removable acrylic resin complete denture to implantsupported fixed prosthesis [4-8,10,14-20].

The multiple clinical challenges (e.g. complex biomechanics, time management and periimplant tissue’ architecture), dictates the type of material required. Generally, the aforementioned techniques are modeled by anecdotal and observational information, and are conveyed from natural tooth provisional techniques.

Contemporary materials for interim prostheses include polymethyl methacrylate (PMM), polyethyl methacrylate, polyvinyl ethyl methacrylate, bis-acryl composite resin, and visible lightpolymerized urethane dimethacrylate [21]. Besides its inherent exothermic reaction [9,22-24] and volumetric shrinkage [23,25-27], PMM have shown-among the literature-better physical properties [9,27-30], color stability [27,31], and durability [9,27,32]. The present technique utilizes an indirect approach, were its fabrication takes place on the laboratory. The indirect technique eliminates the problems associated with the direct technique such as less accuracy on the margins, more chemical and thermal irritants around the tissues and more chances to locked the interim prostheses due to surrounding undercuts [28,29].

By utilizing the indirect technique with PMM in implant dentistry, our expected clinical outcomes have more chances to be colored by the “tincture of time” [33]. The objective of this clinical technique is to present a reliable method for fabricating an immediate interim implant-supported fixed partial denture (FPD) to replace an ailing interim prosthesis.

Clinical Case Report (Replacement of an Ailing Interim Implant-Supported FPD #23-26)

Patient presented to the Post Graduate Operative Dentistry Clinics at Nova Southeastern University with an ailing interim implant-supported acrylic resin (Jet, Lang, Wheeling, IL). FPD replacing the lower anterior incisors. Two Osseo Speed TX 3.5S Astra Tech implants (Dentsply Implants, Waltham, MA) were placed on positions of the lower right and lower left lateral incisors 1 year before the initial appointment. Clinical and radiographical examination of the area and surrounding structures revealed normal conditions; however the interim implant-supported FPD presented grade II mobility, general discoloration and lack of structural integrity (Figures 1A and 1B).The area of the lower anterior incisors as well as 15 mm below were demarcated and posteriorly grinded out on the model (Figure 3), using a Mio Motor (NSK Dental LLC, Hoffman States, IL) with carbide burs. Space was created to allow placement of the implant replicas (Dentsply Implants, Waltham, MA).

Clinically, the provisional abutments (Dentsply Implants, Waltham, MA) and interim FPD were retrieved; periimplant tissue was examined on the implant sites and deemed within normal limits. Copious irrigation using digluconate chlorhexidine (Peridex, 3M, St. Paul, MN) on a plastic syringe was made, to remove plaque and debris from the area. Implant impression copings (Dentsply Implants, Waltham, MA) were adequately screwed on both implants manually. Dental floss (Oral-B Essential floss, Procter and Gamble, Cincinnati, OH) was tied between the implant impression copings, followed by an application of pattern resin (Duralay, Reliance Dental Mfg. Co., Worth, IL) extended towards the incisal edges and occlusal surfaces of adjacent teeth (Figure 4). Subsequently, the implant impression coping-pattern resin unit was carried out intraorally.

On the laboratory, implant replicas were screwed to their respective implant impression copings and subsequently positioned on the model using dental stone (Microstone, Whip Mix, Louisville, KY) (Figure 5A). The implant impression coping-pattern resin unit was unscrewed from the implant replicas (Figure 5B). A new set of a screw-retained interim FPD was built using metallic provisional abutments (Dentsply Implants, Waltham, MA) in conjunction with an indirect technique and acrylic resin (Jet, Lang, Wheeling, IL).

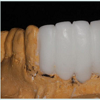

After finishing and polishing, the interim FPD was disinfected following manufacturer’s recommendations. Clinical try-in confirmed adequate insertion, interproximal contacts and occlusion. Subsequently, the prosthesis was screwed in place following manufacturer’s recommendations using a torque of 15 N/cm2 (Figure 6A). Patient was satisfied with clinical outcomes. Postoperative instructions were discussed; emphasis was given to maintain proper oral hygiene, avoid chewing solids and provide post-operative inputs. The definitive porcelain-fused-to-metal implant-supported FPD, was placed 2 months later (Figure 6B).

Clinical Significance

The described technique offers the following advantages: (1) provides the nonparallel abutments with an immediate alternative to reestablish occlusion and esthetics, (2) reduces the time of relining hence, less heat is generated intraorally, (3) minimizes chair side time on the subsequent appointment, since most of the procedures are completed before the patient’s next visit, and (4) reduces time of direct contact between PMM and periimplant tissue. Nonetheless, the present technique is not recommended for single appointments; and the use of the dental stone, pattern resin and extra implant components add extra cost to the treatment.References

- Donovan TE, Cho GC (1999) Diagnostic provisional restorations in restorative dentistry: the blueprint for success. J Can Dent Assoc 65: 272-275.

- Pjetursson BE, Asgeirsson AG, Zwahlen M, Sailer I (2014) Improvements in implant dentistry over the last decade: comparison of survival and complication rates in older and newer publications. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 29 Suppl: 308-324.

- Burns DR, Beck DA, Nelson SK; Committee on Research in Fixed Prosthodontics of the Academy of Fixed Prosthodontics (2003) A review of selected dental literature on contemporary provisional fixed prosthodontics treatment: report of the Committee on Research in Fixed Prosthodontics of the Academy of Fixed Prosthodontics. J Prosthet Dent 90: 474-497.

- Moscovich MS, Saba S (1996) The use of a provisional restoration in implant dentistry: a clinical report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 11: 395-399.

- Neale D, Chee WW (1994) Development of implant soft tissue emergence profile: a technique. J Prosthet Dent 71: 364-368.

- Breeding LC, Dixon DL (1996) Transfer of gingival contours to a master cast. J Prosthet Dent 75: 341-343.

- Saba S (1997) Anatomically correct soft tissue profiles using fixed detachable provisional implant restorations. J Can Dent Assoc 63: 767-768,770.

- Chalifoux PR (1989) Temporary crown and fixed partial dentures: new methods to achieve esthetics. J Prosthet Dent 61: 411-414.

- Vahidi F (1987) The provisional restoration. Dent Clin North Am 31: 363-381.

- Proussaefs P (2002) The use of healing abutments for the fabrication of cement-retained, implant-supported provisional prostheses. J Prosthet Dent 87: 333-335.

- Sze AJ (1992) Duplication of anterior provisional fixed partial dentures for the final restoration. J Prosthet Dent 68: 220-223.

- Preston JD (1976) A systematic approach to the control of esthetic form. J Prosthet Dent 35: 393-402.

- Yuodelis RA, Faucher R (1980) Provisional restorations: an integral approach to periodontics and restorative dentistry. Dent Clin North Am 24: 285-303.

- Listgarten MA, Lang NP, Schroeder HE, Schroeder A (1991) Periodontal tissues and their counterparts around endosseous implants. Clin Oral Implants Res 2: 1-19.

- Lewis S (1995) Anterior single-tooth implant restoration. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 15: 30-41.

- Mitrani R, Phillips K, Kois JC (2005) An implant-supported, screw-retained, provisional fixed partial denture for pontic site enhancement. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent 17: 673-678.

- Ganddini MR, Tallents RH, Ercoli C, Ganddini R (2005) Technique for fabricating a cement-retained single-unit implant-supported provisional restoration in the esthetic zone. J Prosthet Dent 94: 296-298.

- Macintosh DC, Sutherland M (2004) Method for developing an optimal emergence profile using heat-polymerized provisional restorations for single-tooth implant-supported restorations. J Prosthet Dent 91: 298-292.

- Chaimattayompol N, Emtiaz S, Woloch MM (2002) Transforming an existing fixed provisional prosthesis into an implant-supported provisional prosthesis with the use of healing abutments. J Prosthet Dent 88: 96-99.

- Cho SC, Shetty S, Froum S, Elian N, Tarnow D (2007) Fixed and removable provisional options for patients undergoing implant treatment. Compend Contin Educ Dent 28: 604-608.

- Shillingburg HT Jr, Sather DA, Wilson EL Jr, Cain JR, Mitchell DL, et al. (2012) Fundamentals of fixed prosthodontics. Fourth Edition, Quintessence Publishing Co. Inc.

- Plant CG, Jones DW, Darvell BW (1974) The heat evolved and temperatures attained during setting of restorative materials. Br Dent J 137: 233-238.

- Lui JL, Setcos JC, Phillips RW (1986) Temporary restorations: a review. Oper Dent 11: 103-110.

- Danilewicz-Stysiak Z (1980) Experimental investigations on the cytotoxic nature of methyl methacrylate. J Prosthet Dent 44: 13-16.

- Lowe RA (1987) The art and science of provisionalization. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 7: 64-73.

- Shavell HM (1988) Mastering the art of tissue management during provisionalization and biologic final impressions. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 8: 24-43.

- Christensen GJ (1996) Provisional restorations for fixed prosthodontics. J Am Dent Assoc 127: 249-252.

- Kaiser DA, Cavazos E Jr (1985) Temporization techniques in fixed prosthodontics. Dent Clin North Am 29: 403-412.

- Capp NJ (1985) The diagnostic use of provisional restorations. Restorative Dent 1: 92, 94-98.

- Krug RS (1975) Temporary crown resin crowns and bridges. Dent Clin North Am 19: 313-320.

- Yannikakis SA, Zissis AJ, Polyzois GL, Caroni C (1998) Color stability of provisional resin restorative materials. J Prosthet Dent 80: 533-599.

- Wang RL, Moore BK, Goodacre CJ, Swartz ML, Andres CJ (1989) A comparison of resins for fabricating provisional fixed restorations. Int J Prosthodont 2: 173-184.

- Donovan TE, Heymann HO (2011) Tincture of time: a vital ingredient for dental success. J Esthet Restor Dent 23: 133-135.