Journal of Nutrition & Health

Download PDF

Research Article

The Impact of Farm-to-School Programming on Youth Nutritional Health Outcomes

Thompson OM1*, Wang C2 and Pavlovich NM3

- 1The Mayor Joseph P. Riley Jr. Center for Livable Communities, South Carolina State, USA

- 2Department of Health and Human Development, Western Washington University, Washington State, USA

- 3Department of Public Health Sciences, University of California Davis, California State, USA

**Address for Correspondence: Thompson OM, The Mayor Joseph P. Riley Jr. Center for Livable Communities, College of Charleston, 66 George Street, Charleston, SC 29424, Phone (843) 953-6752, Fax (843) 953-6757; E-mail: thompsonom@cofc.edu

Citation: Thompson OM, Wang C, Pavlovich NM. The Impact of Farm-to-School Programming on Youth Nutritional Health Outcomes. J Nutri Health. 2018;4(1): 6.

Copyright © 2018 Thompson OM, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Nutrition and Health | ISSN: 2469-4185 | Volume: 4, Issue: 1

Submission: 23 April 2018 | Accepted: 26 May 2018 | Published: 7 June 2018

Abstract

Background: To assess the impact of a school-based garden/farm program on nutritional health outcomes among youth who participated in our pilot farm-to-school initiative.

Methods: We modified and administered previously published questionnaires designed to assess self-reported fruit and vegetable taste preferences and fruit and vegetable intakes among 4th and 5th grade children in two distinct inner-city Title 1 Elementary Schools located within South Carolina during the 2012/2013 academic school year. Pre- and post-program questionnaire data were collected for 68 intervention group participants and 47 non-intervention group participants.

Results: Findings suggest that youth participation in farm-to-school experiential learning activities such as school-based gardening/farming is associated with improved fruit and vegetable taste preferences as well as intakes, which are important implications for public health nutrition policy and practice.

Conclusions: Future research is needed to further explore the impact of farm-to-school experiential learning activities on youth nutritional health outcomes.

Keywords

Farm-to-school; Fruits; Vegetables; Food systems; Youth

Introduction

Low fruit and vegetable intake among youth is a major public health problem in the United States (U.S.) as 22.3% of U.S. children and adolescents fail to meet minimum national fruit and vegetable intake recommendations [1-5]. These data are particularly troubling because inadequate fruit and vegetable intake in childhood is associated with obesity and co-morbid diseases and conditions in childhood and obese children are more likely than their non-obese peers to become obese adults [2,6-18]. In partial response to the childhood obesity crisis in the U.S., the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004 was created, requiring that publicly-funded education agencies develop wellness policies that include nutrition guidelines for foods provided to youth on school campuses [7,19]. The development of the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004 was important as researchers and practitioners alike suggest that schools are key venues for the implementation of public health programs, policies, and initiatives that promote general wellness and seek to prevent and control obesity among youth [20,21]. Not only is school a place where children and adolescents spend the first two decades of their lives [22,23], but it is also a place where they consume about half of their daily kilocalories from school meals and snacks [23-26].

To facilitate building positive relationships between youth and healthful foods such as fruits and vegetables, schools may incorporate some form of healthful food taste education into their school nutrition environments such that students are at the center of the educational activity [5,27,28]. Examples of student-focused, healthful food taste education activities include learning basic cooking skills, taste-testing fresh fruits and vegetables, and growing produce in a school garden/ farm setting [27]. School-based garden/farm initiatives, in particular, can provide ample healthful food taste education opportunities for youth and these initiatives have been gaining ground in the nutrition community as research has shown that youth who are exposed can develop positive taste preferences for fresh, local produce among other health-related outcomes [1,3,12,27]. For example, Evans et al., found that youth who participated in school gardening/farming activities had increased food-related knowledge, which, as suggested by Evans et al. could be a precursor for change in food-related selfefficacy and outcome expectations [11]. Other researchers have found similar results but have also determined that the youth who participated in school gardening/farming activities shifted their taste preferences toward fresh fruits and vegetables [1,5,6,17]. Moreover, and importantly, several researchers have recently demonstrated that youth who participated in school gardening/farming programs increased their actual consumption of fruits and vegetables along with other healthful foods [10,12,29,30]. The purpose of the current study was to assess the impact of a school-based garden/farm program on nutritional health outcomes among youth who participated in our pilot farm-to-school initiative. To achieve this objective, we modified and administered previously published questionnaires designed to assess youth self-reported fruit and vegetable taste preferences and fruit and vegetable intakes to 4th and 5th grade children during the 2012/2013 academic school year who attended two distinct inner-city Title 1 Elementary Schools located within South Carolina, United States (U.S.).

Experimental Methods

Participants

We collected participant characteristic data (i.e., grade, age, and sex) and administered a fruit and vegetable taste preference and intake survey to youth who participated in the experiential learning component of our farm-to-school program (i.e., our school-based farm) during the 2012/2013 academic school year (intervention group) as well as to youth who did not participate (non-intervention or control group). The youth fruit and vegetable intake preference survey was modified adapted from: Bearing Fruit: Farm to School Program Evaluation Resources and Recommendations (http://departments.oxy.edu/uepi/cfi/bearingfruit/htm) and the youth fruit and vegetable intake survey was modified and adapted from: Ratcliffe, M.M. (2007). The effects of school gardens on children’s knowledge, attitudes and behaviors related to vegetable consumption and ecoliteracy. (Doctoral Dissertation, Tufts University). Pre and post participant characteristic and survey data were collected for 68 intervention group participants and 47 non-intervention group participants. The students were 4th and 5th graders aged 8 to 12 years of primarily non-Hispanic black ethnicity and race enrolled in one of two inner-city Title 1 Elementary Schools in South Carolina, (U.S.).

Procedure

The school-based farm was the experiential learning component of our larger, pilot farm-to-school initiative. The farm, which is Good Agricultural Practice (GAP) certified, sits on 1/8 acre of space in a 60’ x 90’ area, roughly 5,500 square feet and is divided into four quadrants by a five-foot gravel pathway. Each quadrant hosts seven 40’ crop rows. In partnership with the city, county, school officials, the farm utilizes city water and is irrigated by an automated drip irrigation system. The farm is a vehicle for teaching students math and science concepts and about where their food comes from while at the same time teaching lessons of respect, teamwork, accountability, and entrepreneurship. Instruction is year-round, classes meet outside at the farm bi-weekly for hour-long experiential learning activities (i.e., seed propagation, growing and harvesting fruits and vegetables, plant and soil health, cooking and ultimately marketing and selling produce to the school’s cafeteria, local restaurant sponsors, and at local farmers’ markets).

Data analysis

Data were cleaned, coded, and then analyzed using STATA (StataCorp 2011. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). Descriptive statistics were calculated for all of the continuous and categorical variables including age, sex, grade level, and school (intervention school vs. non-intervention school) to summarize basic demographic characteristics. Preliminary analyses were conducted using chi-square analyses and the Student’s t-test, as appropriate, to determine statistically significant differences in participant characteristics between intervention group and nonintervention group study participants. Logit/Probit regression models were used to check the intervention effects for main outcomes (fruit and vegetable preference as well as fruit and vegetable intakes) adjusting for sex and grade level. This statistical analysis technique was applied because outcome variables were recorded as binary. Logit or Probit regression models were chosen according to the results of goodness-of-fit tests (using Pseudo-R2). The following model was used to examine the intervention effects on outcomes:

Outcomes (Fruit and Vegetable Preferences and Fruit and Vegetable Intakes) = α+ Group + Time + Group*Time + Sex + Grade +ε(1)

For all analytical tests, a two-sided probability of p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Research procedures were approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board.

Results

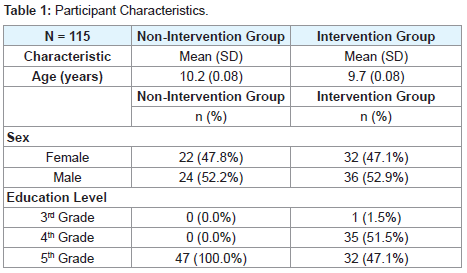

Demographic characteristic data for participants with complete pre- and post-test data (N = 115; 68 intervention group participants and 47 non-intervention group participants) are presented in Table 1. Twenty-two girls (47.8%) and 24 boys (52.2%) were in the nonintervention group and 32 girls (47.1%) and 36 boys (52.9%) were in the intervention group. All participants in the non-intervention group were in the 5th grade, while approximately half of the participants in the non-intervention group were in the fourth grade and the other half were in the fifth grade.

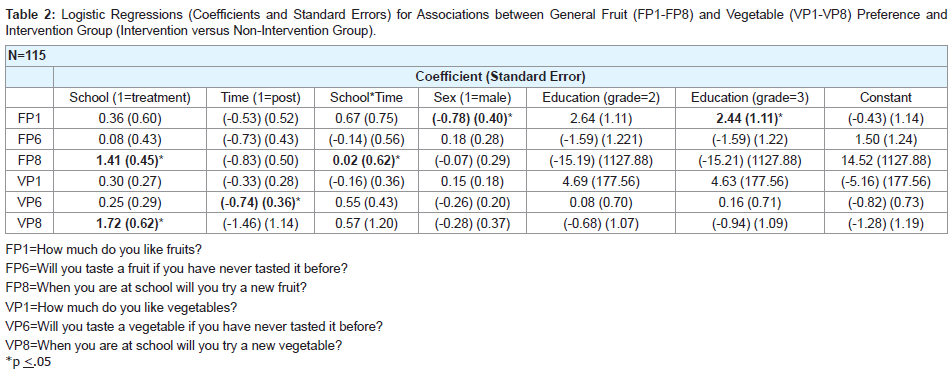

Data pertaining to participants’ preference and willingness to taste a new fruit/vegetable in community, home, and school environments are reported in Table 2. Data revealed that students in the non-intervention group were more likely to try a new fruit at school compared to students in the non-intervention group, from pre- to post-test controlling for gender and grade level. No statistically significant differences were observed for preference and willingness to taste a new vegetable between students in the intervention and nonintervention groups, however. Interestingly, boys were less likely than girls to report “liking fruits a lot” when controlling for intervention, time, and grade level.

Table 2: Logistic Regressions (Coefficients and Standard Errors) for Associations between General Fruit (FP1-FP8) and Vegetable (VP1-VP8) Preference andIntervention Group (Intervention versus Non-Intervention Group).

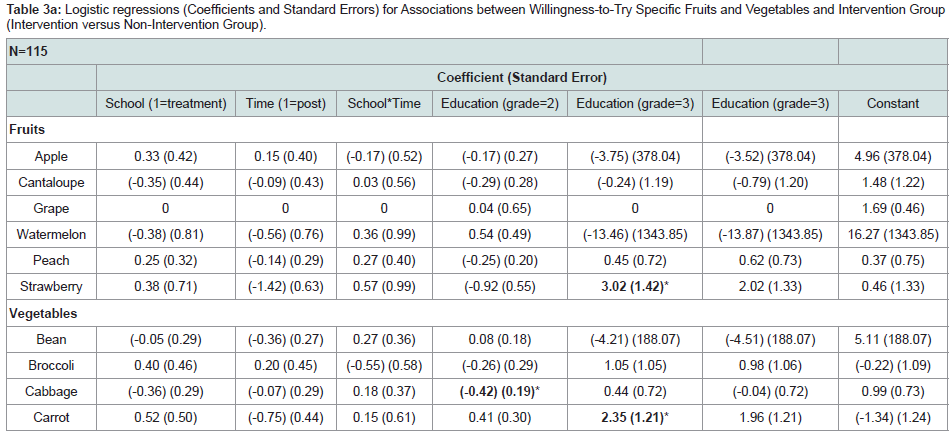

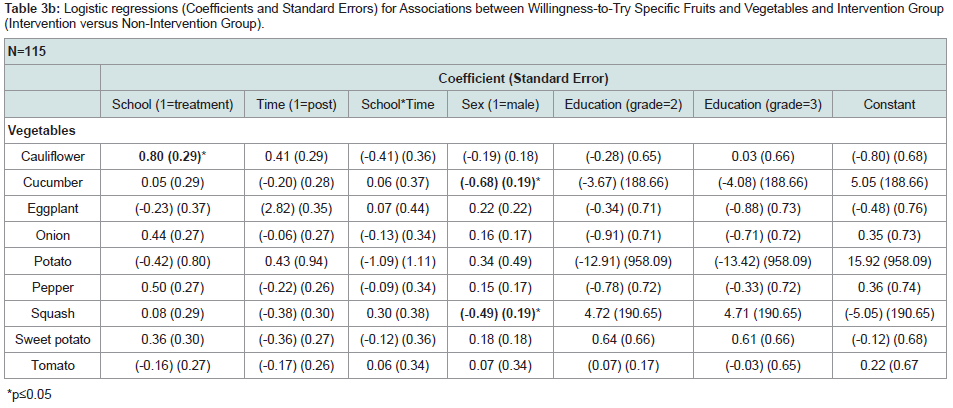

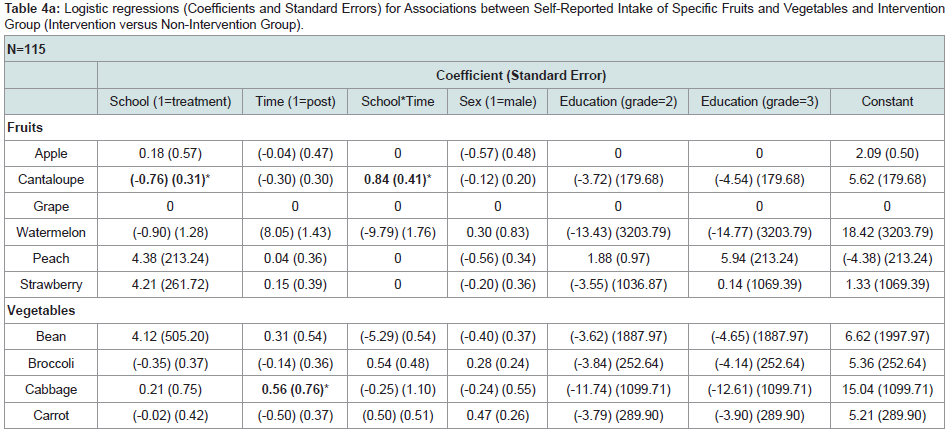

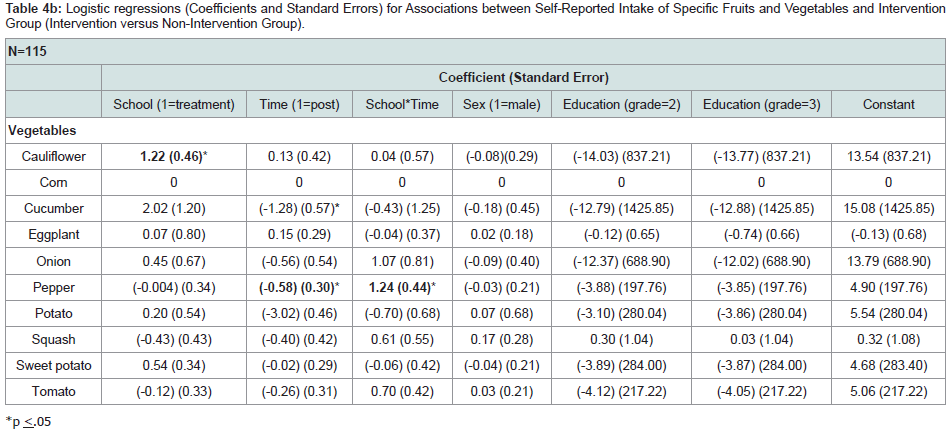

Data pertaining to participants’ preference for the six fruits and 14 vegetables evaluated are reported in Table 3a & b. Data revealed that there were no statistically significant intervention effects for fruit and vegetable preference. However, students in the intervention group were more likely to “like” cauliflower than students in the nonintervention group, controlling for sex and grade level. Moreover, compared to girls, boys were less likely to “like” cabbage, cucumbers, and squash, controlling for grade level. Data pertaining to participants’ fruit and vegetable consumption for the six fruits and 14 vegetables evaluated are reported in Table 4a & b. Data revealed that statistically significant increases for fruit and vegetable consumption among students in the intervention group occurred for both cantaloupe and peppers.

Table 3a: Logistic regressions (Coefficients and Standard Errors) for Associations between Willingness-to-Try Specific Fruits and Vegetables and Intervention Group (Intervention versus Non-Intervention Group).

Table 3b: Logistic regressions (Coefficients and Standard Errors) for Associations between Willingness-to-Try Specific Fruits and Vegetables and Intervention Group (Intervention versus Non-Intervention Group).

Table 4a: Logistic regressions (Coefficients and Standard Errors) for Associations between Self-Reported Intake of Specific Fruits and Vegetables and Intervention Group (Intervention versus Non-Intervention Group).

Table 4b: Logistic regressions (Coefficients and Standard Errors) for Associations between Self-Reported Intake of Specific Fruits and Vegetables and Intervention Group (Intervention versus Non-Intervention Group). Discussion

To assess the impact of a school-based garden/farm program on nutritional health outcomes among youth who participated in our pilot farm-to-school initiative, we modified and administered previously published questionnaires designed to assess youth selfreported fruit and vegetable taste preferences and intakes to 4th and 5th grade children during the 2012/2013 academic school year who attended one of two inner-city Title 1 Elementary Schools located within South Carolina, United States (U.S.). Study findings, while modest, suggest that participation in the school-based garden/farm program was associated with positive taste preference for a variety of fruits and vegetables as well as increased fruit and vegetable intakes among youth - results that are consistent with those from previous researchers.

For example, Morris and Zidenberg-Cherr conducted research at three schools from a local school district in Davis, California and found that students who were exposed to nutrition education and a gardening curriculum showed greater preferences for fruits and vegetables as well as increased nutrition knowledge compared to students who were in the control group, even at 6-months post intervention [1]. Similarly, Somerset et al. conducted a 12-month school-based garden intervention trial with 4th to 7th grade students enrolled in a state primary school within a low socioeconomic area of Brisbane, Australia. These researchers found that the intervention led to improvements in students’ abilities to not only identify vegetables and fruits, but to prepare them for consumption [15]. Furthermore, in a 12-week quasi-experimental, garden-based intervention with predominately Latino 4th and 5th grade students in Los Angeles, Gatto et al. assessed student motivations and preferences for fruits and vegetables [6]. In this study, researchers found that vegetable and fruit preferences as well as self-efficacy increased among participating youth compared to non-participating youth from pre- to postintervention.

Heim et al. conducted a U.S. based 12-week pilot intervention with 4th to 6th grade youth attending a YMCA summer camp. In this study, youth were exposed to one of three groups: (1) a school gardening and nutrition education group, (2) a nutrition education only group, or (3) a control or unexposed group. These researchers found that youth who were exposed to both school gardening and nutrition education conditions were more willing to taste a variety of unfamiliar fruits and vegetables, compared to youth who were only exposed to nutrition education or who were not exposed to either condition [3]. Similarly, Morgan et al. conducted a 10-week intervention trial with 5th and 6th grade students enrolled in two primary schools in the Hunter Region of New South Wales, Australia [16]. These researchers found that of the three study groups, youth who participated in garden-enhanced nutrition education were more willing to taste new fruits and vegetables and reported positive taste references compared to youth who participated in non-gardenenhanced nutrition education.

In addition to improving knowledge, preferences, and self-efficacy for fruits and vegetables, researchers have also found that schoolbased garden/farm programs can increase students’ overall intake of fruits and vegetables. For example, McAleese and Rankin conducted a 12-week study on 6th grade students at three different elementary schools in southeast Idaho. These researchers found that students who participated in nutrition education and gardening activities significantly increased their intakes of fruits and vegetables as well as selected nutrients such as vitamin A, vitamin C and fiber [12]. Evans et al. measured the effects of different levels of exposure to a multiplecomponent, garden-based intervention on students from five middle schools in ethnically diverse communities in Austin, Texas. These researchers found that students who were exposed to the multiplecomponent school garden intervention reported increased intakes of fruits and vegetables and related self-efficacy and knowledge and decreased preference for unhealthy foods or foods that did not meet the USDA’s newly reformed nutrition standards [11,31-34].

Conclusion

A recent joint initiative released by Michelle Obama, the Surgeon General, and the Department of Health and Human Services on January 28th, 2010 called for healthier school environments, improved dietary and physical behaviors at home, and community engagement efforts to improve the health of our nation’s youth [30,35]. To support this initiative, President Obama issued a memorandum calling for the establishment of a federal task force to combat the childhood obesity epidemic specifically [30,36]. In 2008, the Institute of Medicine Committee on Childhood Obesity Prevention Actions for Local Governments cited the implementation of youth-gardens in communities as a promising and innovative way to promote the consumption of fruits and vegetables and prevent childhood obesity [37]. For example, as explained in Ratcliffe M’s Polytheoretical Model for Food and Garden-Based Education, school-based garden programs provide a real-world context for learning that is distinguishable from other hands-on learning activities [38]. This model suggests that food and garden-based education programs directly affect relationships between students and health-promoting and environmentally responsible behaviors. Moreover, as Story et al. noted, school gardens act as outdoor “learning laboratories” that offer multiple opportunities for students to gain food systemrelated knowledge, skills, and abilities as well as serving as a setting for positive youth development [23]. School gardens/farms can improve a school’s physical and social learning environments [38-40] as they visually reinforce learning and can positively influence social norms around eating [38,40]. In summary, our findings combined with those from previous researchers suggest that school garden/farm programs can improve nutritional health outcomes by shifting youth taste preferences toward fresh, local fruits and vegetables and by increasing actual fruit and vegetable intakes.

Implications for Future Research

School-based garden/farm programs, important components of farm-to-school initiatives, can serve as advocacy tools for nutritionfocused obesity prevention and control efforts [23,29] - gardens/farms are tangible and thus make farm-to-school efforts real. Moreover, according to researchers and practitioners alike, long-lasting beneficial changes to youths’ nutritional health can be secured by coordinating a comprehensive garden/farm-enhanced nutrition education program with school wellness policies, offering healthful foods on school campuses, fostering family and community partnerships, and supporting local agriculture [13,23,30,41]. Farm-to-school initiatives also appeal to many food system stakeholders, including farmers, sustainable agriculture and environmental advocates, community and school garden supporters, waste/ recycling supporters, school administrators and teachers, parents, food/agriculture businesses, community development folks, farmland preservation advocates, government agencies, universities and cooperative extension, and food service, to name a few [13,30,42].

References

- Morris JL, Zidenburg-Cherr S (2002) Garden-enhanced nutrition curriculum improves fourth-grade school children’s knowledge of nutrition and preferences for some vegetables. J Am Diet Assoc 102: 91-93.

- Johnston CA, Moreno JP, El-Mubasher A, Woehler D (2012) School lunches and lunches brought from home: a comparative analysis. Child Obes 8: 364-368.

- Heim S, Stang J, Ireland M (2009) A garden pilot project enhances fruit and vegetable consumption among children. J Am Diet Assoc 109: 1220-1226.

- Condon EM, Crepinsek MK, Fox ML (2009) School meals: types of foods offered to and consumed by children at lunch and breakfast. J Am Diet Assoc 109: S67-S78.

- Oxenham E, King AD (2010) School gardens as a strategy for increasing fruit and vegetable consumption. J Child Nutr Man 34: 1-5.

- Gatto NM, Ventura EE, Cook LT, Gyllenhammer LE, Davis JN (2012) LA Sprouts: a garden-based nutrition intervention pilot program influences motivation and preferences for fruits and vegetables in Latino youth. J Acad Nutr Diet 112: 913-920.

- Briefel RR, Crepinsek MK, Cabili C (2009) School food environments and practices affect dietary behaviors of US public school children. J Am Diet Assoc 109: S91-S107.

- Christian MS, El Evans C, Conner M, Ransley JK, Cade JE (2012) Study protocol: can a school gardening intervention improve children’s diets? BMC Public Health 304.

- Ohri-Vachaspati P, Turner L, Chaloupka FJ (2012) Fresh fruit and vegetable program participation in elementary schools in the United States and availability of fruits and vegetables in school lunch meals. J Acad Nutr Diet 112: 921-925.

- Harris DM, Seymour J, Grummer-Strawn L, et al. (2012) Let’s move salad bars to schools: a public-private partnership to increase student fruit and vegetable consumption. Child Obes 8: 294-297.

- Evans A, Ranjit N, Rutledge R, Medina J, Jennings R, et al. (2012) Exposure to multiple components of a garden-based intervention for middle school students increases fruit and vegetable consumption. Sage Journals 13: 608-616.

- McAleese JD, Rankin LL (2007) Garden-based nutrition education affects fruit and vegetable consumption in sixth-grade adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc 107: 662-665.

- Feenestra G, Ohmart J (2012) The evolution of the school food and farm to school movement in the United States: connecting childhood health, farms, and communities. Child Obes 8: 280-289.

- Roche E, Conner D, Kolodinsky JM, Buckwalter E, Berlin L, et al. (2012) Social Cognitive Theory as a framework for considering farm to school programming. Child Obes 8: 357-363.

- Somerset S, Markwell K (2008) Impact of a school-based food garden on attitudes and identification skills regarding vegetables and fruit: a 12-month intervention trial. Public Health Nutr 12: 214-221.

- Morgan PJ, Warren JM, Lubans DR, Saunders KL, Quick GI, et al. (2009) The impact of nutrition education with and without a school garden on knowledge, vegetable intake and preferences and quality of school life among primary-school students. Public Health Nutr 13: 1931-1940.

- Robinson-O’Brien R, Story M, Heim S (2009) Impact of garden-based youth nutrition intervention programs: a review. J Am Diet Assoc 109: 273-280.

- Davis EM, Cullen KW, Watson KB, Konarik M, Radcliffe J (2009) A fresh fruit and vegetable program improves high school students’ consumption of fresh produce. J Am Diet Assoc 109: 1227-1231.

- Jaeschke, Elizabeth M, Schumacher, Julie Raeder, Cullen (2012) Perceptions of principals, teachers, and school food, health, and nutrition professionals regarding the sustainability and utilization of school food gardens. J Child Nutr Manag 36: 1-7.

- Hoffman JA, Franko DL, Thompson DR, Power TJ, Stallings VA (2010) Longitudinal behavioral effects of a school-based fruit and vegetable promotion program. J Ped Psyc 35: 61-71.

- Kakarala M, Keast DR, Hoerr S (2010) Schoolchildren’s consumption of competitive foods and beverages, excluding a` la carte. J Sch Health 80: 429-435.

- Wordell D, Daratha K, Mandal B, Bindler R, Butkus SN (2012) Changes in a middle school food environment affect food behavior and food choices. J Acad Nutr Diet 112: 137-141.

- Story M, Nanney MS, Schwartz M (2009) Schools and obesity prevention: creating school environments and policies to promote healthy eating and physical activity. Milbank Q 87: 71-100.

- Cohen JFW, Smit LA, Parker E, Austin SB, Frazier AL, et al. (2012) Long-term impact of a chef on school lunch consumption: findings from a 2-year pilot study in Boston middle schools. J Acad Nutr Diet 112: 927-933.

- Condon EM, Crepinsek MK, Fox MK (2008) School meals: types of foods offered to and consumed by children at lunch and breakfast. J Am Diet Assoc 109: 67-78.

- Caird J, Kavanagh J, O’Mara-Eves A (2013) Does being overweight impede academic attainment? A systematic review. J Health Educ.

- Nowak AJ, Kolouch G, Schneyer L, Roberts KH (2012) Building food literacy and positive relationships with healthy food in children through school gardens. Child Obes 8: 392-395.

- Nelson MC, Lytle LA, Pasch KE (2009) Improving literacy about energy-related issues: the need for a better understanding of the concepts being energy intake and expenditure among adolescents and their parents. J Am Diet Assoc 109: 281-287.

- Wright W, Rowell L (2010) Examining the effect of gardening on vegetable consumption among youth in kindergarten through fifth grade. WMJ 109: 125-129.

- Scherr RE, Cox RJ, Feenstra G, Zidenberg SC (2013) Integrating local agriculture into nutrition programs can benefit children’s health. California Agriculture 67: 30-37.

- United States Department of Agriculture. (2012) USDA Unveils Historic Improvements to Meals Served in America’s Schools (accessed May 13, 2015).

- Haynes-Maslow L, Parsons SE, Wheeler SB, Leone LA (2013) A qualitative study of perceived barriers to fruit and vegetable consumption among low-income populations, North Carolina. Prev Chronic Dis 10: 120206.

- 33.Hartline-Grafton H (2010) How competitive foods in schools impact student health, school meal programs, and students from low-income families (accessed May 14th, 2015).

- Belansky ES, Cutforth N, Gilbert L, Litt J, Reed H (2013) Local wellness policy 5 years later: is it making a difference for students in low-income, rural Colorado elementary schools? Prev Chronic Dis 10: 1-10.

- Health and Human Services (2010) Secretary and surgeon general join first lady to announce plans to combat overweight and obesity and support healthy choices (accessed April 16th, 2015).

- Let’s Move (2010) Report to the president: solving the problem of childhood obesity within a generation (accessed April 12th, 2015).

- Institute of Medicine (2009) Local government actions to prevent childhood obesity (accessed April 12th, 2015).

- Ratcliffe MM (2012) A sample theory-based logic model to improve program development, implementation, and sustainability of farm to school programs. Child Obes 8: 315-322.

- Graham H, Zidenberg-Cherr S (2005) California teachers perceive school gardens as an effective nutritional tool to promote healthful eating habits. J Am Diet Assoc 105: 1797-1800.

- Joshi A, Ratcliffe MM (2012) Causal pathways linking farm to school to childhood obesity prevention. Child Obes 8: 305-314.

- Briggs M, Fleischhacker S, Mueller CG (2010) Position of the American dietetic association, school nutrition association, and society for nutrition education: comprehensive school nutrition services. J Nutr Educ Behav 42: 360-371.

- Lawrence K, Liquori T (2012) School food: point of view matters. Child Obes 8: 327-330.