Journal of Geriatrics and Palliative Care

Download PDF

Research Article

*Address for Correspondence: Danforn Lim, Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales,PO Box 3256, Blakehurst, NSW 2221 Australia, E-mail: celim@unswalumni.com

Citation: Ho K, Lim CED, Cheng NCL, Zaslawski C. ACEPAC Study - Australian Chinese patient’s Experiences of Palliative Care Services. J Geriatrics Palliative Care 2014;2(2): 8.

Copyright © 2014 Danforn Lim et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use,distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Geriatrics and Palliative Care | ISSN 2373-1133 | Volume: 2, Issue: 2

Submission: 27 March 2014| Accepted: 20 May 2014 | Published: 26 May 2014

Reviewed & Approved by: Dr. Egidio Del Fabbro, Associate Professor in the Division of Hematology, Oncology and Palliative Care of the Department of Internal Medicine at the VCU School of Medicine, USA.

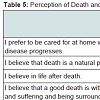

No significant results were found when comparing mean scores of each statement by demographic characteristics: number of years in Australia and language spoken at home when the Mann-Whitney U test was performed. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.729, which showed high reliability of the questions.

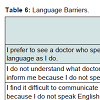

Statistically insignificant results were found when the Mann-Whitney U test was performed to determine differences between mean scores of each statement by demographic variables. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.546, which showed low reliability.

A Mann-Whitney U test indicated that the preference to see a doctor who speaks the same language in Cantonese speakers (Mean rank = 22.71, n = 28) were significantly higher than those of Mandarin speakers (Mean Rank = 13.09, n = 11), (U = 78.000, z = -2.550 (corrected for ties), p = 0.011). The other results were insignificant. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.809, which showed high reliability.

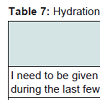

Table 7 reports a summary of the results. No other significant results were found. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.860, which showed high reliability.

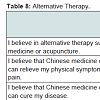

The Mann-Whitney U test was insignificant when mean scores of each statement was compared with demographic variables. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.830, which showed high reliability.

ACEPAC Study - Australian Chinese patient’s Experiences of Palliative Care Services

Khai Ho1, Chi Eung Danforn Lim1,2*, Nga Chong Lisa Cheng1 and Christopher Zaslawski2

- 1 South Western Sydney Clinical School, University of New South Wales, Australia

- 2 School of Medical and Molecular Biosciences, University of Technology Sydney, Australia

*Address for Correspondence: Danforn Lim, Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales,PO Box 3256, Blakehurst, NSW 2221 Australia, E-mail: celim@unswalumni.com

Citation: Ho K, Lim CED, Cheng NCL, Zaslawski C. ACEPAC Study - Australian Chinese patient’s Experiences of Palliative Care Services. J Geriatrics Palliative Care 2014;2(2): 8.

Copyright © 2014 Danforn Lim et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use,distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Geriatrics and Palliative Care | ISSN 2373-1133 | Volume: 2, Issue: 2

Submission: 27 March 2014| Accepted: 20 May 2014 | Published: 26 May 2014

Reviewed & Approved by: Dr. Egidio Del Fabbro, Associate Professor in the Division of Hematology, Oncology and Palliative Care of the Department of Internal Medicine at the VCU School of Medicine, USA.

Abstract

Background: Australia is a multicultural country that consists of a diverse population. It can be difficult to provide equal healthcare services across all ethnicities due to cultural disparities. This is seen amongst Australian Chinese to under-utilize healthcare services such as palliative care.Objective: This study aimed to explore the Australian Chinese’s understanding of palliative care service and on their end-of-life care preferences so that suitable support and services that are culturally appropriate could be delivered to them.

Methods: Participants were recruited from two Chinese cancer support group organizations in Sydney to complete a self-reported questionnaire on their understanding of palliative and end-of-life care preferences. 41 Chinese participants were recruited from four support group sessions.

Results: Seven themes were explored. The majority of participants understood the role of palliative care and would accept the service. They favored being informed about the nature of their condition even during advanced stages. Many preferred making decisions for their own treatment but highly valued the advice from doctors and family members. Most participants were open to discuss issues related to death and dying and the need for interpreter services was highlighted. They viewed that nutrition and hydration as necessity during end-of-life and many believed in a combined regimen of western and alternative therapy to treat their condition.

Conclusion: This study shows that Australian Chinese understand the role of palliative care. Changes in perception in areas such as disclosure of the truth of a disease and openness in discussing issues related to death and dying are highlighted. Traditional Chinese values still play a role in shaping their attitudes regarding decision-making and hydration and nutrition during end-of-life care. Further research to explore the generalisability of these results is warranted.

Keywords

Chinese; Palliative care; Clinical service; AustraliaIntroduction

Palliative care services are provided by a variety of health professionals with the goal to deliver quality end-of-life care to patients who are terminally-ill, their carers and family members [1]. It aims to prevent and relieve patients’ suffering from physical symptoms such as pain and provide psychosocial, emotional and spiritual support of patients and their family members [2,3]. The focus of palliative care is not only limited to cancer care, but it also includes care for any chronic irreversible illnesses such as multiple sclerosis, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, Alzheimer’s disease and advances respiratory, kidney and heart disease [4].As Australia is a multicultural country with a diverse population, it is seen to be a challenge to provide equal palliative care services towards all patients from different cultural backgrounds [5]. In Sydney, 33.4% of its population is born overseas and 31.4% of them speak a language other than English at home [6]. People born in China are one of the largest groups of overseas-born residents in Australia, accounting of a proportion that has increased from 0.8% to 1.8% over the last 10 years [7].

“Ethnic, racial or cultural disparities exist at all levels of healthcare, including palliative care” [8]. Most cultures integrate belief fundamentals that may influence their actions or thoughts [9,10]. It is postulated that due to cultural disparities, palliative care services are often found to be under-utilized especially by minorities such as foreign-born and non-English speaking patients [8,9,11,12]. These patients are also often under-treated, resulting in unnecessarily suffering and poorer outcomes [10,13]. It is also well-known that language barriers are one of causes of difficulty in accessing and utilising healthcare services [14]. A study found that Chinese in Australia believe that they may be receiving lower standard of care compared to Australian-born people, and this could be attributed by difficulties in communication or perceived disadvantage against foreign citizens [5,13].

During end-of-life circumstances, it is common for Chinese to rely on their family members and doctors instead of taking an individual responsibility approach in decision-making [13,15]. This is because Chinese view the provision of care to those who are ill is their family’s and doctor’s responsibility as a way to show love and respect [1,5,10,16,17]. Therefore, some minority groups in Australia, e.g., the Chinese, view that the emphasis on autonomy neglects values such as family integrity and physician responsibility during decision-making [13]. A study also found that Australian Chinese value specialist’s advice highly and they trust that their doctors will make the most appropriate decision for the best patient outcome [13].

In traditional Chinese culture, it is important not to disclose the truth of an illness to patients, especially for serious health conditions such as cancer [13,18]. They fear that the individual cannot cope with their disease by knowing the truth, therefore leading to an early death [19,20,21]. A study showed that Australian Chinese preferred to be told of their condition through a number of consecutive appointments with their doctor as this will allow them to be prepared to accept the truth [5]. Family members also request doctors to withhold certain information regarding patient’s health condition from them [13,16]. Hence, it is difficult for doctors to fulfill their role in informing patients of their exact condition and available treatment options [22].

It was found that the utilization of palliative care among the Chinese is generally infrequent [16]. A study conducted in a focus group setting showed that Australian Chinese did not know about palliative care services [5]. Another survey which was conducted in Hong Kong also showed that only a minority of the people (10.5%) were willing to receive information on palliative care [23]. Death and dying is also a taboo subject to discuss among the Chinese [16,17]. Australian Chinese were found to be uncomfortable with talking about issues related to death and dying [5]. This situation presents a challenge for palliative care doctors to discuss about end-of-life care preferences with them [16].

The Chinese also have a very different perception regarding hydration and nutrition as eating is a very important aspect of Chinese culture [17]. They view that preparing food for their loved ones is a way to show care and concern [17]. Chinese believe it is the family’s duty to feed the patient as much as they can, regardless of whether they are clinically capable of doing so or not. This traditional view often conflicts with the medical practice of administering nutritional supplement to the terminally-ill where it emphasizes on the provision of sufficient rather than excessive nutritional support [24] as well as to do no harm to the patient.Limited studies have been conducted among Australian Chinese regarding their views and beliefs towards understanding the role of palliative care and end-of-life care preferences. As the Chinese community has been in Australia for a substantial period of time, a considerable large ageing population is present to warrant the need to explore recent trends regarding these issues [13,25]. It is important to understand their attitudes and perspectives in order to identify possible areas of improvement so that palliative care services can be amended to be better-suited for the Chinese community. Therefore, this study was aimed to explore the understanding of palliative care and end-of-life care preferences among Australian Chinese and to establish associations between demographic characteristics and various themes.

Methods

Sampling and data collectionThe study was approved by the Biomedical Human Research Ethics Advisory Panel at the University of New South Wales, Australia. Prospective participants were recruited during four support group sessions organized by two voluntary and non-profit making Chinese cancer support organizations in Sydney-namely CanRevive and CanCare Centre. Surveys were kept anonymous and confidentiality of personal details was ensured and participation in the questionnaire was voluntary.

The patient information statement & consent form and questionnaire were available in both English Language and simplified Chinese language. A total of 41 cancer patient participants were recruited from four support group sessions and no one refused to join the study.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire consisted of a short section of introductory questions and a section on different statements across seven themes. A total of 35 statements were categorized into seven subgroups, namely “understanding of palliative care”, “truth-telling and disclosure”, “decision-making”, “perception of death and dying”, “language barriers”, “hydration and nutrition&rdquo and “alternative therapy”. Each subgroup consisted of 5 statements except for “understanding of palliative care” which consisted of 6 statements and “truth-telling and disclosure” consisted of 4 statement. The statements were measured using a five-point Likert scale format. The questionnaire was made available in both English and Simplified Chinese Languages. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated for each subgroup to determine the internal consistency and reliability of the questions and the value of > 0.7 showed high reliability.

Data analysis

Data was entered twice for the purpose of comparing two copies of the same data in order to eliminate errors while entering them. Descriptive statistics were produced for the answers and the mean score for each statement was determined. A Mann-Whitney U test was performed to compare mean scores of each statement by demographic variables. Demographic variables included number of years in Australia and most common language spoken at home. Only two groups -“Cantonese” and “Mandarin” were used for comparison whereas two other groups - “Shanghainese” and “both Cantonese and Mandarin” were omitted as the sample size was too small. A two tailed p-value of less than 0.05 is considered statistical significant. All analyses were done using SPSS v20.0 for Windows.

Results

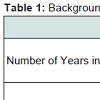

Sample characteristics41 Chinese participants participated in completing the questionnaire. They had been living in Australia in between 0.6 years to 52 years, with a mean of 19.1 years (SD = 10.5 years). The most common language spoken at home was Cantonese. Table 1 is a summary of the sample characteristics of the participants.

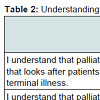

Each of the statements has a potential mean score from one through five. The general trend showed majority of the participants agreed and strongly agreed with statements related to understanding of palliative care. Most participants understood that palliative care is a specialty that looks after patients with irreversible or terminal disease with a mean score of 3.70 (SD = 0.883). Most agreed that they understood that palliative care focuses on giving care during advanced disease rather than cure, which received a mean score of 3.85 (SD = 0.963).

Many of them understood that palliative care manages their physical symptoms, emotions and spiritual need, scored a mean score of 4.05 (SD = 0.773). They also knew that support would be offered to their family members by the palliative care team to cope as their disease progressed with a mean score of 4.12 (0.640). Many believed that they would benefit from receiving palliative care services, received a mean score of 4.15 (SD = 0.864). Majority of them wished to manage their physical symptoms with assistance from the palliative care team, scored a mean score of 4.17 (SD = 0.704). Table 2 reports participant’s understanding of palliative care.

No significant results were found when comparing mean scores of each statement by demographic characteristics: number of years in Australia and language spoken at home when the Mann-Whitney U test was performed. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.729, which showed high reliability of the questions.

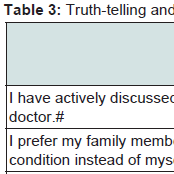

Truth-telling and disclosure: With regards to truth-telling and disclosure, most participants had actively discussed their conditions with their doctors. This statement received a mean score of 3.90 (SD = 0.583).

Many participants disagreed that they preferred not to be told everything of their condition if it was a potentially fatal disease, with a mean score of 2.15 (SD = 1.038). They disagreed that their family members should know about their condition instead of themselves, received a mean score of 2.88 (SD = 1.144). Most participants denied being afraid that they would have difficulty coping if they were told that their disease was incurable, with a mean score of 2.40 (SD = 0.982). More details were on Table 3.

Statistically insignificant results were found when the Mann-Whitney U test was performed to determine differences between mean scores of each statement by demographic variables. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.546, which showed low reliability.

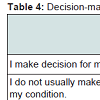

Decision-making: The majority of the participants agreed that they made decisions for their treatment, with a mean score of 4.05 (SD = 0.740). Most of the participants disagreed that they do not usually make any medical decision for their condition, received a mean score of 2.63 (SD = 0.968).

Many participants agreed that they allowed other people e.g. family members, doctors and etc. to make medical decisions for them, with a mean score of 3.63 (SD = 0.888). However, most participants trust their doctors and family members to make the best decision for them. The former received a mean score of 3.85 (SD = 0.615) while the latter received a mean score of 3.37 (SD = 1.043). Table 4 is a summary of the results.

No statistical differences were determined when the Mann-Whitney U test was done. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.659, which showed low reliability.

Perception of death and dying

Table 5 summarizes participant’s perspective related to death and dying. All participants believed that death is a natural process of life, scored a mean score of 4.27 (SD = 0.449). Most participants believed that a good death is one that occurs without pain and suffering and where one can be surrounded by family members, received a mean score of 3.76 (SD = 0.767). A majority of the participants had a neutral perspective towards believing in the life after death, and this scored amean score of 3.00 (SD = 1.177).

When their disease progressed, the majority of the participants wished to be cared for at home, with a mean of 3.44 (SD = 0.976). They disagreed with not discussing issues related to death and dying as it is against their culture, scored with a mean score of 2.46 (SD= 1.002). Statistically insignificant results were obtained when the Mann-Whitney U test was performed. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.280, which showed low reliability.

The majority of the participants preferred to see a doctor who speaks the same language as they do, with a mean score of 3.85 (SD= 0.989). A possible reason could be many participants did not understand what doctors are trying to inform them because they do not speak English, with a mean score of 3.13 (SD = 1.159). Many also found it difficult to communicate with their doctor because they do not speak English, scored a mean score of 3.32 (SD = 1.150). Therefore, many require the assistance of interpreters to translate information from doctors, received a mean score of 3.49 (SD = 1.227). Most patients found that the presence of an interpreter was helpful as they disagreed with finding it difficult to understand their doctor’s advice with the interpreter services, a mean score of 2.65 (SD = 0.921). (Table 6)

A Mann-Whitney U test indicated that the preference to see a doctor who speaks the same language in Cantonese speakers (Mean rank = 22.71, n = 28) were significantly higher than those of Mandarin speakers (Mean Rank = 13.09, n = 11), (U = 78.000, z = -2.550 (corrected for ties), p = 0.011). The other results were insignificant. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.809, which showed high reliability.

Hydration and nutrition

Chinese participants believed that hydration and nutrition was important during end-of-life, where all five statements had mean scores of more than 3.00. The majority of the participants believed that nutrition and hydration will do more good than harm to their bodies, scored a highest mean score of 4.15 (SD = 0.691). This belief was significant higher in Cantonese speakers (Mean rank = 22.02, n =28) compared to Mandarin speakers (Mean Rank = 13.09, n = 11), (U = 97.500, z = -2.007 (corrected for ties), p = 0.045). They also believed that having nutrition and hydration could prolong their lives; this received the lowest mean score of 3.71 (SD = 0.844).

The majority of the participants needed to be given nutrition and hydration even during the last few days of their lives, scored a mean score of 4.02 (SD = 0.724), with Cantonese speakers (Mean Rank = 22.46, n = 28) possessing a significant stronger view compared to Mandarin speakers (Mean Rank = 13.73, n = 11), (U = 85.000, z = -2.525 (corrected for ties), p = 0.012). Most of the participants wanted to be fed by other methods such as nasogastric tube and total parenteral nutrition when pronounced nil by mouth, scored a mean score of 3.76 (SD = 0.799). Many of them also believed that nutrition and hydration should not stop until the person passes away, with a mean score of 3.78 (SD = 0.909). However, these attitudes were more pronounced among the Cantonese speakers. Cantonese speakers (Mean rank = 22.48, n = 28) were more likely to prefer being fed by other methods compared to Mandarin speakers (Mean Rank = 13.68, n = 11), (U = 84.500, z = -2.422 (corrected for ties), p = 0.015). Cantonese speakers (Mean Rank = 22.48, n = 28) were also more likely to request the continuation of nutrition and hydration until one passes away, when compared to Mandarin speakers (Mean Rank = 13.68, n = 11), (U = 84.500, z = -2.408 (corrected for ties), p = .016).

Table 7 reports a summary of the results. No other significant results were found. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.860, which showed high reliability.

Alternative therapy: Many participants believed in alternative therapy such as Chinese medicine or acupuncture, received a mean score of 3.59 (SD = 0.948). They believed that Chinese medicine or acupuncture can relieve their physical symptoms such as pain, a mean score of 3.61 (SD = 0.945). However, the majority of the participants disagreed that Chinese medicine or acupuncture can cure their disease, scored a mean score of 2.88 (SD = 0.927).

Many participants believed in a combined treatment regimen that consisted of both western and alternative therapy, with a mean score of 3.95 (0.677) and most of them even expected that doctors could assist them in working out a combined treatment regimen for their disease which received a mean score of 4.24 (SD = 0.734). Details of the results could be seen on Table 8.

The Mann-Whitney U test was insignificant when mean scores of each statement was compared with demographic variables. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.830, which showed high reliability.

Discussion

This study suggests that Australian Chinese has a good understanding of the role of palliative care in the hospital and community setting. Most participants acknowledge that palliative care is a discipline that looks after patients with irreversible or terminal illness. It focuses on giving care rather than providing a cure during advanced disease. They also understand that palliative care manages physical symptoms, emotions and provides spiritual care as well as needs of their family members. Many participants wish to manage their physical symptoms with assistance from palliative care team and believe that they will benefit from the service. This may suggest that Australian Chinese have a high acceptance of palliative care services which is inconsistent with a study conducted in Hong Kong where patients are generally more reluctant to receive services from palliative care [9]. Such difference could be due to palliative care playing a more established and active role in the Australian healthcare system. Palliative Care Australia started a National Community Education Initiative in 2009 to deliver support and education by providing palliative care information and resources in multilingual languages to the community [26]. Resources available in patient’s native language are more effective in assisting them to clearly understand the aim and purpose of palliative care, including addressing their myths and misconceptions regarding the service. The huge emphasis on effective communication and interaction between doctors, patients and family members in Australia also enables them to realize that palliative care is a discipline that focuses to improve the quality of life for terminal patients.Attitudes towards truth-telling and disclosure among Australian Chinese in this study are somewhat different compared to what is seen in the traditional Chinese culture. Traditional Chinese culture believes that the truth of an illness, especially for terminal conditions such as cancer should not be disclosed to patients [18,20]. This is because they are afraid that patients will be too stressful to cope with the reality, resulting in an early death [18,20,27]. However, this study found that most participants have actively discussed their conditions with their doctors and expressed their desire to be informed of the full truth of their disease including prognostic issues. This is consistent with a recent survey conducted among the seriously ill Chinese, Japanese and Koreans where most of them wanted to hear about the truth of their condition directly and frankly from their doctors when they progress into a terminal stage [28]. Most participants are also not afraid of the difficulty of coping if they are told that they have an incurable disease. The changing attitudes among Australian Chinese may be caused by the influence of Western culture, where society is generally promoting human rights and exercising autonomy. They might be positively inclined towards being informed and to be in control of their situation, especially after being in Australia for a substantial period of time.

In terms of decision-making, the majority of the participants make decisions for their treatment. However, many of them also allow and trust other people such as doctors and family members to make the best medical decisions for them. This may indicate that Australian Chinese value the advice from doctors, family members and their closed ones during decision-making. Subsequently, family members are often strongly involved in making important decisions such as medical treatment [1,21]. This is a reflection of the traditional Chinese culture where family members are often seen as an entity rather than individuals within that entity [10]. Australian Chinese in this study also practice the attitude of trusting doctor’s expertise and believe that their doctors are suggesting the most appropriate treatment plan for their conditions. This result is consistent with a study conducted among Australian Chinese by Huang et al. [13]. Knowing that they possess such mindset, it is important to inform them that during the process of medical decision-making, doctors, family members and their closed ones may give good advice but they have the right to make their own choices according to their circumstances.

All participants in this study believe that death is a natural process of life. The majority of the participants have a neutral opinion towards life after death suggesting that this belief could be a religious belief instead of a cultural belief (as religion was not explored in this study). At the terminal stages of their lives, most participants preferred to be cared for at home, where this result is consistent with a study done among Australia Chinese [5]. Australian Chinese may feel more comfortable being taken care of in a more familiar place during terminal stages. Many of them also believe that a good death is without pain and suffering and being surrounded family members. Hence, it is important to manage their symptoms adequately and notify their loved ones during advanced stages so that they will be able to see them before passing away [17]. As seen in this study, discussing death and dying is no longer a taboo to all Chinese. This is consistent with a study conducted among Chinese in Hong Kong where participants are willing to discuss about their perception on death and dying [29]. It reflects a changing trend regarding this attitude among the Chinese. This could be due to the fact that contemporary Australian Chinese are more open with wanting to let their wishes known so that preparations could be made before passing on.

Language barrier still seems to be present among Australian Chinese as majority of the participants prefer to see a doctor who speaks the same language as they do. Many of them require the need of an interpreter because incompetency in speaking in English prevents them from communicating with their doctors and understanding information given. As a significantly higher preference to see a doctor who speaks the same language is seen amongst Cantonese speakers compared to Mandarin speakers, this suggests that more Cantonese interpreters are needed to provide the service. The presence of an interpreter is essential during a consult to prevent patients from feeling more distressed when communication becomes a barrier [13]. In this study, many of them who receive interpretation service find that interpreters are helpful in assisting them to communicate with their doctors.

The results of this study indicate that Australian Chinese may possess a miss-perception regarding nutrition and hydration during their terminal stages. These misunderstandings include nutrition and hydration will only do more good than harm to one’s body, prolong lives, feeding needs to be continued relentlessly and only should stop when one passes away. This result is consistent with a study conducted in Taiwan where palliative care patients were found to feel that they were given insufficient nutritional support during their stay in hospital [24]. It is indeed true that eating is a very important part of Chinese culture. However, they need to understand that inappropriate feeding may be detrimental as it will further aggravates patient’s conditions resulting in disorders such as gastrointestinal secretions, limb oedema and ascites [24,30]. Effective interaction between doctors, patients and family members is vital when discussions surrounding nutrition and hydration occur so that the misconception on excessive feeding can be sensitively and explicitly addressed. To prevent the loved ones of patients from feeling anxious, it should be explained to them that stopping the feed of terminally-ill patients do not indicate that patients are suffering a poor quality of life and are starving to death [19]. From this study, Cantonese speakers seem to have a more significant misunderstanding compared to the Mandarin speakers. The difference between Cantonese and Mandarin speakers may highlight the diversity of views and preferences within the Australian Chinese community itself. Therefore, doctors should be weary of generalized views of the Chinese population influencing their practice.

Treatment using a combination of western medicine and alternative therapy is widely accepted among the participants in this study. Many participants believe that alternative therapy such as Chinese medicine or acupuncture can relieve their physical symptoms such as pain. They also expect that doctors will be able to help them to work out a combined regimen for their disease. This is consistent with a study performed among Australian Chinese [31]. As the usage of alternative therapy among Australian Chinese is generally accepted, doctors should be aware of its usage in order to prevent any contraindications with medications being administered. With the emerging evidence supporting the effectiveness of Chinese medicine and acupuncture for symptom control, a combined treatment regimen should be gradually recognized and accepted as an effective approach in managing a disease.

We cannot find the difference in perceptions towards understanding of palliative care and end-of-life preferences regardless of the duration of Chinese living in Australia. It may suggest that traditional Chinese values among Australian Chinese are still being preserved and they play an important role in shaping some of their thoughts and attitudes towards end-of-life care. This would propose the need of culturally appropriate support and treatment to be implemented so that palliative care service would be widely accepted and utilized by the Chinese community.

In conclusion, Australian Chinese in this study understandthe role of palliative care and wish to accept the service. This study highlights a change in perception in areas such as disclosure of the truth of their disease and openness in discussing issues related to death and dying. However, some attitudes are still highly influenced by the traditional Chinese values such as decision-making and the need for nutrition and hydration during end-of-life care. Although this study provides an updated insight on their views, it is restricted by a small sample size, limited demographic details and participant recruitment sites. Further research to explore a more generalized perception in understanding of palliative care and end-of-life preferences among Australian Chinese is warranted. A qualitative methodology to provide a more in-depth viewpoint regarding their experiences and knowledge of palliative care should also be conducted.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the two voluntary Chinese cancer support group organizations namely CanRevive Australia and Cancare Centre Australia for helping us to recruit the subjects in this study. We would also like to thank Emily Hung, Sabrina Man, Venus Fung, and Jeremy & Wendy Ho, for proving assistance in patient recruitment during support group sessions. I also appreciate the help of the translator who was involved in translating the patient information statement & consent form and questionnaire for the purpose of this project. Finally, we sincerely appreciate the participation of all participants who volunteered their time in completing the questionnaire.References

- Chater K and Tsai C (2008) Palliative care in a multicultural society: a challenge for western ethics. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 26: 95-100.

- Claxton-Oldfield S, Claxton-Oldfield J and Rishchynski G (2004) Understanding of the term “palliative care”: A Canadian survey. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 21: 105-110.

- WHO (2012) WHO definition of palliative care.

- Addington-Hall J (2002) Research sensitivities to palliative care patients. Eur J Cancer Care 11: 220-224.

- McGrath P, Vun M, and McLeod L (2001) Needs and experiences of non-English-speaking hospice patients and families in an English-speaking country. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 18: 305-312.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2011) National Regional Profile: Sydney (Statistical Division).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics - Migration, Australia, 2010-11. (2012).

- Kemp C (2005) Cultural issues in palliative care. Semin Oncol Nurs 21: 44-52.

- Reese DJ, Chan CL, Chan WC, Wiersgalla D (2010) A Cross-National Comparison of Hong Kong and U.S. Student Beliefs and Preferences in End-of-Life Care: Implications for Social Work Education and Hospice Practice. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 6: 205-235.

- Bowman KW and Singer PA (2001) Chinese seniors’ perspectives on end-of-life decisions. Soc Sci Med 53: 455-464.

- Owens A and Randhawa G (2004) ‘It’s different from my culture; they’re very different’: providing community based, ‘culturally competent’ palliative care for South Asian people in the UK. Health Soc Care Community 12: 414-421.

- Clark K, Phillips J (2010) End of life care: The importance of culture and ethnicity. Aust Fam Physician 39: 210-213.

- Huang X, Butow P, Meiser B, Goldstein D (1999) Attitudes and information needs of Chinese migrant cancer patients and their relatives. Aust N Z J Med 29: 207-213.

- Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, Mutha S (2006) Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res.. 42: 727-754.

- Clayton JM, Butow PN, and Tattersall MH (2005) The needs of terminally ill cancer patients versus those of caregivers for information regarding prognosis and end-of-life issues. Cancer 103: 1957-1964.

- Chiu TY, Hu WY, Chuang RB, Cheng YR and Chen CY, et al. (2004) Terminal cancer patients' wishes and influencing factors toward the provision of artificial nutrition and hydration in Taiwan. J Pain Symptom Manage 27: 206-214.

- Ho ZJ, Radha Krishna LK and Yee CP (2010) Chinese familial tradition and Western influence: A case study in Singapore on decision making at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 40: 932-937.

- Tung W (2011) Hospice care in Chinese culture: A challenge to home care professionals. Home Health Care Management & Practice 23: 67-68.

- Wong MS and Chan SW (2007) The experiences of Chinese family members of terminally ill patients-a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs 16: 2357-2364.

- Yun YH, Kwon YC, Lee MK, Lee WJ, Jung KH, et al., (2010) Experiences and attitudes of patients with terminal cancer and their family caregivers toward the disclosure of terminal illness. J Clin Oncol 28: 1950-1957.

- Chan A and Woodruff RK (1999) Comparison of palliative care needs of English-and non-English-speaking patients. J Palliat Care 15: 26-30.

- Chan WC (2011) Being Aware of the Prognosis: How Does It Relate to Palliative Care Patients' Anxiety and Communication Difficulty with Family Members in the Hong Kong Chinese Context? J Palliat Med 14: 997-1003.

- Hancock K, Clayton JM, Parker SM, Wal der S, Butow PN, et al. (2007) Truth-telling in discussing prognosis in advanced life-limiting illnesses: a systematic review. Palliat Med 21: 507-517.

- Mjelde-Mossey LA and Chan CL (2007) Survey on Death and Dying in Hong Kong. Soc Work Health Care 45: 49-65.

- Chiu TY, Hu WY, Cheng SY, Chen CY, et al. (2000) Ethical dilemmas in palliative care: a study in Taiwan. J Med Ethics 26: 353-357.

- Kwak J and Haley WE (2005) Current research findings on end-of-life decision making among racially or ethnically diverse groups. Gerontologist 45: 634-641.

- Palliative Care Australia (2011) National Community Education Initiative.

- Searight HR and Gafford J (2005) Cultural diversity at the end of life: issues and guidelines for family physicians. Am Fam Physician 71: 515-522.

- Ivo K, Younsuck K, Ho YY, Sang-Yeon S, Seog HD, et al. (2012) A survey of the perspectives of patients who are seriously ill regarding end-of-life decisions in some medical institutions of Korea, China and Japan. J Med Ethics 38: 310-316.

- Chan HY and Pang S (2007) Quality of life concerns and end-of-life care preferences of aged persons in long-term care facilities. J Clin Nurs 16: 2158-2166.

- Chiu TY, Hu WY, Huang HL, Yao CA, Chen CY (2009) Prevailing ethical dilemmas in terminal care for patients with cancer in Taiwan. J Clin Oncol 27: 3964-3968.T