Journal of Forensic Investigation

Download PDF

Research Article

The Impact of Culture and Belief in So-Called Honour Killings A Comparative Study between Honour Murders and other Perpetrators of Violence in Germany

Kizilhan JI1,2*

1Institute for Psychotherapy and Psychotraumtology, University of

Duhok, Iraq

2Institute of Transcultural Health Science, State University Baden-

Württemberg, Germany

*Address for Correspondence: Dr. Kizilhan JI, State University Baden-Württemberg Schramberger

Str. 26, D-78054 Villingen-Schwenningen,Germany, Tel:4977203906-

217;Fax: 497720 3906-219; Email: kizilhan@dhbwvs.de

Submission: 19 August, 2019;

Accepted: 28 August, 2019;

Published: 03 September, 2019

Copyright: © 2019 Kizilhan JI, et al. This is an open access article

distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Although the experts assume that, in addition to general

psychosocial stress, culture-specific and migration-related factors

play a part in the criminal tendencies of migrants, there has not

been much research done to date on the special situation of those

persons committing honour killings. This study starts from the premise

that these perpetrators have a patriarchal-religious mind-set and

have developed a conception of “honour”. In connection with

biographical stresses they are more willing to injure or kill other people

if the values and standards they believe in are not respected. We

interviewed 41 men with a Turkish background between 18and 35in

Germany who had killed other persons who they thought had violated

their concept of honour and who then had been convicted of murder

or manslaughter (“honour killers”). The two control groups comprised

44 criminals with an ethnic Turkish background who were in prison on

charges of using violence without causing death and 40 prisoners who

had been convicted of murder or manslaughter for other reasons.

To ascertain the respective motives for their actions, we used semistandardised

interviews in jails. Compared to the control groups, the

group of honour killers revealed significant differences as regards

ethnicity and socialisation, structural violence in their country of origin

and stresses within the family. We found a correlation between the

parameters “reinforcement through the social milieu” and “costbenefit

considerations”, “ancestry and socialisation” and “structural

violence”. In the case of the honour killers we found strong patriarchalreligious

cognitions with structural violence which triggered actionoriented

and target-oriented aggression when the person concerned

felt that the standards and values which he believed in, had been

infringed.

Keywords

Honour killings; Psycho-social stress; Culture, Aggression; Beliefs

Introduction

According to the 2010 United Nations Population Fund Activities

(UNPFA) at least 5,000 women and girls worldwide are killed

annually in the name of honour. These so-called honour killings are

not a religious but rather a social phenomenon: It is true that they

frequently occur in Islamic countries, yet they are not confined to

these [1,2]. Women and girls in at least 14 countries are affected,

including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Brazil, Germany, Ecuador, Italy,

Jordan, Palestine, Pakistan, Turkey, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon [3,4].

Above all, so-called honour killings occur in traditional societies

whose members have a patriarchal-archaic notion of honour linked to religious elements [5]. In traditional societies with patriarchal

values and norms, women embody honour in a narrower sense.

The expression of a women’s honour, and therefore the family’s

honour, is sexual integrity, i.e. chastity and being faithful in marriage.

The whole family, represented by the head of the household as the

boss, is responsible for the maintenance of women’s honour [6].

In patriarchal societies honour is closely connected to sexuality.

Extramarital sexual activity endangers the social order: This is why

Islam gives clear instructions on how men and women are to behave

within and outside marriage [7].

The top priority – and the men’s task – is the protection and

preservation of honour. As head of the household the father must

ensure that the family’s honour is protected in public. The sons see

themselves – and are brought up in this way – to be their sisters’

protectors, protectors of their honour, which could be violated, for

example, by their relationship with a man [8,9]. This constant fear

and insecurity results in the brothers’ exercising control over the

young girls and sometimes even monitoring their movements–

particularly in an environment which is differently oriented from

a religious-cultural point of view. This can have a considerable

influence on the relationships between the siblings and in the whole

family [10]. Since there is a homogeneous set of values in traditional

village communities, such controls are not as necessary as in other

environments, and breaches of the rules are quite rare.

In the case of so-called honour killings, for example the German

Criminal Code does not explicitly refer for exemaple to human rights,

but rather discusses morality and legality, and can classify them as

deviating values of a cultural minority, e.g. “ honour killings “. Moral

beliefs of the perpetrator that contradict those of the majority are

just as irrelevant in criminal law as ideas that overlap with those of

the majority. Honour killings are seen as murders and sentenced

according to the German Penal Code [11].

In many other countries, the so-called honour killings still were

not treated as a violation of human rights but were treated as normal crimes by the respective national legislators. It is only the pressure

from numerous human rights organisations during the last years

which has brought about a greater readiness to view this issue from

the perspective of human rights [12]. For example, over the last

ten years in Turkey some civil rights movements have dealt more

intensively with the topic. On 08.03.2005 the Turkish newspaper

Hürriyet reported on the work of KAMER, the women’s centre in

Diyarbakir, and that up to then some 6,902 women had been to the

centre to report violence in the immediate or in the extended family.

According to information provided by the centre, 100% of these

women were suffering from mental health problems; some 58% had

suffered physical violence and 13.7% had experienced rape. More

than 65 women with strong suicidal tendencies had sought help at

the centre, 63 of these are being accommodated in an unknown and

safe place because of the fear that they could be killed on account

of the possible violation of honour and blood vengeance. In a study

conducted by the University of Diyarbakir in 2005, 430 people were

asked about the topic of honour killing. 78% men and 22% women

were randomly chosen from one of the more affluent parts of the

town. They were asked what should be done if a woman enters into

an extramarital affair with a man. 37.4% advocated having the woman

killed. However, 16% called for only a punishment. The punishment

under consideration was physical injury and mutilation e.g. cutting

the ears or the nose. Regarding the question as to who should inflict

this punishment, 64% voted for the husband. 25% of those interviewed

advocated divorce through the proper legal channels [13].

Such honour killings are not only carried out in the home

country, but also in the country of migration. According to a Federal

Criminal Police (2011), between 1996 and 2005 in Germany alone, at

least 55 such murders and attempted murders took place, with a total

of 70 victims, of which48 were female and 22 male. 36 women and 12

men were killed [14]. The killers considered that the female victims

had had an extramarital affair, either before marriage (virginity) or

with a man of a different religion. The male victims, as a rule, were

murdered by members of the woman’s family or other close family

members of the woman with whom they had had an affair. There are

isolated cases of female killers. They kill for the same reasons, namely

what they believe to be a violation of honour [15,16] reports that

the perpetrators say they felt a deep inner urge to carry out the act

and that they had lost their inner peace, that the other person had

challenged them and that they would have lost their own honour if

they had not carried out the act. From what we can conclude from

this investigation we can say that, as a rule, the perpetrators give

emotional and psychological reasons for their acts. Honour killings

for material, political or religious reasons were not considered

[17].

Possible approaches from a criminal-psychological perspective:

Criminal-psychological research tries to understand acts of

violence, amongst other things, as the result of an interactive

process involving the personality of the individual perpetrator and

the facts of the situation at the time [18]. The present study uses the

action-theoretical and motivation-psychological models and the

interpretations of several authors. These can possibly explain some

differences regarding the planning, the controlled implementation

and the emotional state before and after the act, in the case of bodily harm, robbery or the emotional intimacy to the victim [19-21]. Common to these approaches, crimes can be considered as acts which serve to reach a target and/or to solve a problem. [22]

showed, for instance, that young murderers decide to commit an act

at short notice and do not plan carefully over a longer time. [23-25]

made it clear that robberies were often prepared without considering

any details and at short notice. The perpetrator, however, usually

believes that he planned the act thoroughly. [20] established the link

between poor preparation and the use of violence. He explained

that the escalation which is often observed in acts of violence was

due to poor preparation. According to Simons, the pressure to act

makes the perpetrator hurry and gives him no time to prepare. This

and other investigations show how important it is to include actiontheoretical

concepts in order to make criminal acts of violence more

understandable [26-28].In the scientific literature, criminal acts of violence are

understood as a sub-group of violent actions. Violent actions in turn

can be understood as a sub-section of aggressive actions. The border

between aggression and violence is not clear; the concept of “violence”

tends to be reserved for extreme forms of aggressive actions, that is,

for aggressive actions leading to the greater probability of significant

injuries to the victim [29]. As a sub-group of violent actions, criminal

acts of violence comprise violent actions forbidden by the state under

the threat of punishment. In criminology literature, a “criminal act”

is frequently referred to simply as a “crime”. According to [30], crime

is an extremely valueless and socially deviant kind of behaviour. The

various forms of crime are defined in legal terms in the criminal code

(StGB); this investigation is oriented towards the legal definitions

contained in the code.

The reasons for committing a criminal offence are many, for

migrants and indigenous people alike. In various studies, cultural and

migration-related stress has also been discussed [31]. The deprivation

theory as an explanatory approach focuses in particular on the

migrants’ socio-structural situation. The argument goes that they are

often disadvantaged since they more rarely have secondary education

qualifications and are employed in the low-paid sector. This is not

only a problem because they earn below-average wages but also

because their jobs are less secure. For this reason migrants are more

often affected by unemployment and receive social security benefits.

They are not able to reach their personal targets by their own

means. This causes frustration and is compensated for by acquiring

the necessary means in a different way, among other things by

robbery and theft [32]. The theory assumes that migrants are more

conspicuous and attract attention because of their marginalised

social situation. In the same situation German people would probably

behave in exactly the same deviant way.

Cultural explanations augment this point of view. They

concentrate not only on the marginalised economic situation but

also on specific orientations within the migrant groups. According to

the sub-culture theory and the theory of cultural conflict, not all the

norms and values of a society are valid to the same degree in all social

circles. This can be amply illustrated by considering the understanding

of honour, as discussed earlier. Migrants do not simply drop such

cultural convictions when they come to Germany. To date there

have been no scientific studies on the perpetrators who have killed somebody whom they believe has violated honour. For this reason,

in this study we want to investigate, by means of direct questioning,

the cognitive processes, the possible stress factors and the purpose

of the crime. The Rubicon model of action phases [33] was used as a

framework model with special reference to honour killers. The model

uses four definable phases which are necessary to reach a desired

aim. They are choosing, planning, enacting and evaluating, in each

case with a specific mind-set. The concept of the “pre-scene” by [34]

was complemented in order to provide some inner structure to the

enaction phase.

Method

Random Test:

For purposes of comparison we questioned 65 male test persons

of Turkish descent about the crime they had committed and their

biographical details. The random test was divided into the following

three categories of crime: so-called honour killers (N = 21), violence

not resulting in death(N=24) and murder or manslaughter for other

reasons(N = 20). In the case of the last group we tried to exclude

any possibly latent honour killing by means of pre-interviews and

inspection of the person’s file. The so-called honour killers were

convicted pursuant to §§ 211 and 212 of the criminal code (StGB), the

group violence not resulting in death pursuant to §§ 223, 224, 226, 229

and 231 of the criminal code and the group murder or manslaughter

for other reasons pursuant to §§ 211 and 212 of the criminal code. To

enable a better comparison of the groups and to avoid any possible

interferences (ethnic and religious differences as regards values and

norms such as a different understanding of honour in the case of

the Alevs or other non-muslim groups from the Middle East etc.),

we selected only ethnic Turkish perpetrators belonging to the Sunni

faith. No female test persons were found for the group investigated.At the time of the investigation the test persons were in prison

and were interviewed there. They had all committed their crime

aged between 18and 35years old. As the reason for their action the

honour killer group gave the violation of honour as they perceived it;

the group violence not resulting in death substantiated their actions

with uncontrolled aggression (43%), robbery and deception (33%)

and relationship problems (24%). Violations of honour which could

possibly have been the cause of the crime in both control groups were

excluded by means of pre-interviews and by consulting the case files.

The group murder or manslaughter for other reasons gave robbery and deception (60%) and uncontrolled aggression (40%) as the

motive for their crime.

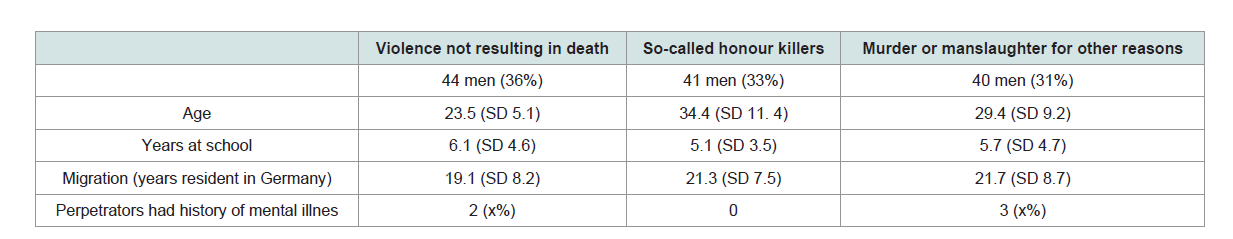

The mean age of the ethnic Turkish group of honour killers was

34.4 years (standard deviation = 10.4); the youngest person was 18,

the oldest 40. The mean age of the murder or manslaughter for other

reasons group was29.4 years (SD = 9.2); the youngest was 20, the

oldest 36. The violence not resulting in death group had a mean age of

23.5 years (SD = 5.1); the youngest person was20, the oldest 33.

The honour killers group had attended school for an average of5.1

years, the group murder or manslaughter for other reasons 5.7 years

and the group violence not resulting in death 8.1 years. The honour

killers group had been living in Germany for an average of 21.3years,

the murder or manslaughter for other reasons group for 21.7years and

the violence not resulting in death group for 19.1years. In the group

violence not resultign death 2 Person and in the group murderoder

mansllaughter 3 Persons had a history of mental illnes without any

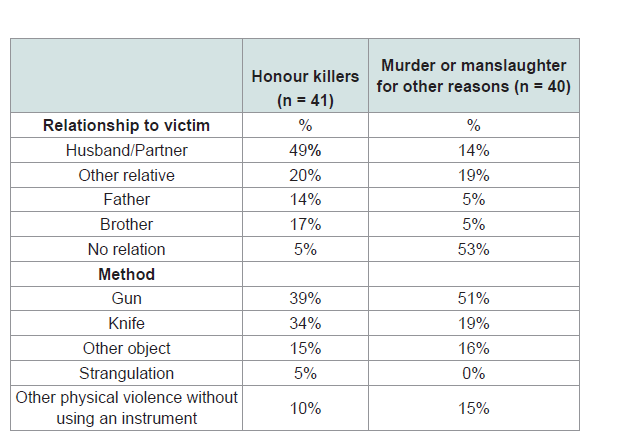

effect on their judgment or live in prison (Table 1). The court files gave

information on the type and method of killing and the relationship

of the perpetrator to the victim. The violence not resulting in death

group had no family ties to the victim and the instruments were so

varied and numerous that we could not adequately compare them

with the other two groups.

Data Material and Processing:

The data on which the analysis is based was gathered between

May 2018 and May 2019. This time span was necessary in order

to locate the so-called honour killers via the courts and prisons, to

overcome the many legal hurdles and to obtain the perpetrators’

consent to being interviewed (Table 2). Test persons for the group

to be investigated were found by means of media research, contact to expert testifiers and judges. Those test persons in the groups who said

they had not carried out a crime on account of a perceived violation

of honour were excluded from the study. With the help of a semistandardised

interview, we asked a total of 65 perpetrators in various

prisons in the whole of Germany about the crime they had committed

and about their biographical background. Prior to this, we looked at

the court sentences. To enable a statistical analysis, answers were

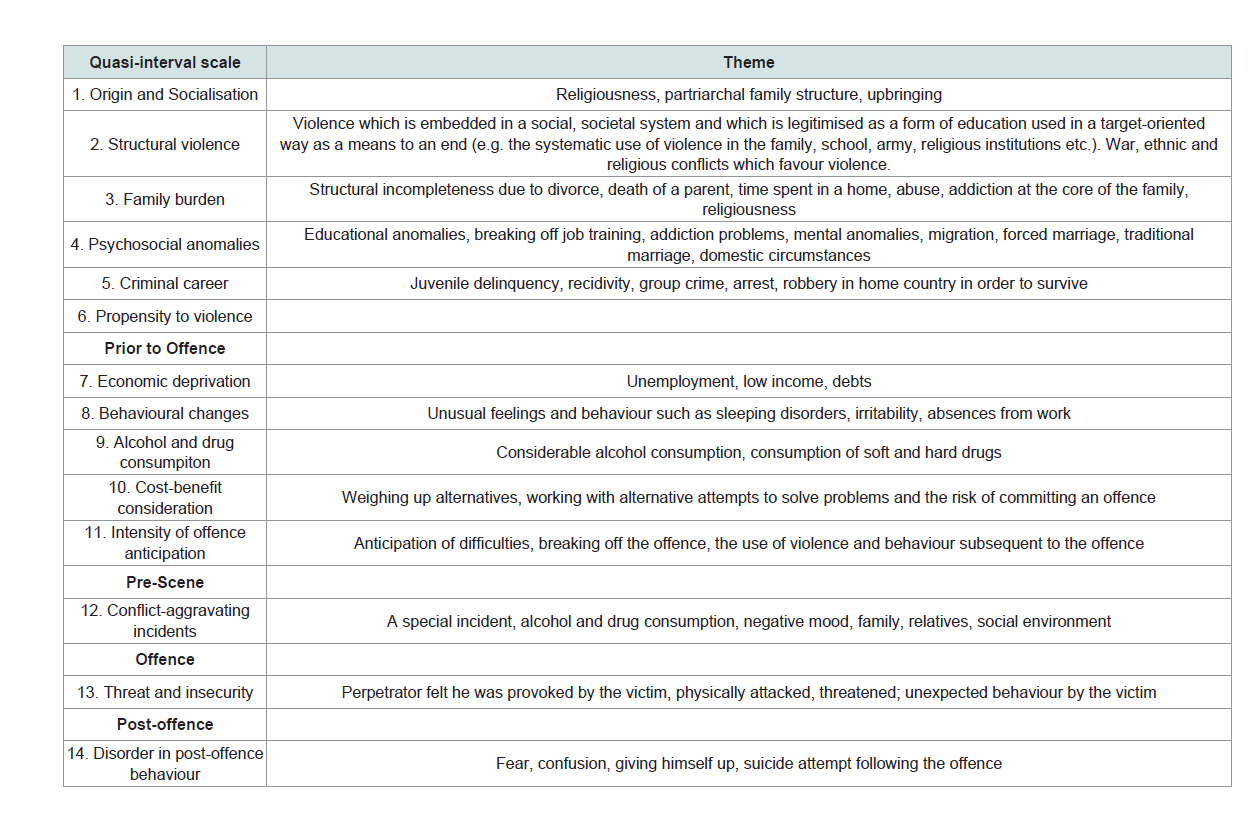

coded and dichotomised according to fixed contextual criteria. The

variables obtained were summarised as per [37] and later according

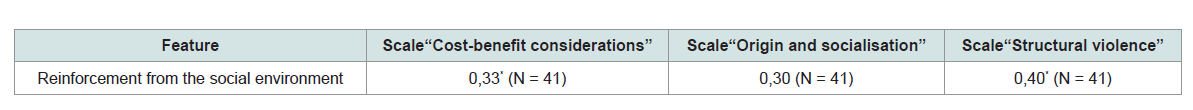

to [38] according to thematic considerations in 14 quasi scales (Table 3).We also considered the variable reinforcement by the social

environment. We included this variable if the social environment

(family, relatives, friends or members of a community) reinforced the

test person’s intentions, praised him for his actions during his time in

prison or during the court hearing and gave him recognition (e.g. a

visit from his family of origin, presents etc.).

The choice of variables which we considered relevant were

based, in particular, on the work of [39-41]. We added questions

which oriented towards the Rubicon model of action phases of [42]

and expanded them to include culture-specific aspects. We devised

open and closed interview questions for each topic area which we

considered relevant. The answers to the closed interview questions

were binary coded. For example, if the answer to the question “Has

anybody in your family been in prison?” was “Yes”, we coded it with a

“1”, and for “No”, we coded it “0”. The coded answers then formed the variable for the “Imprisonment of family members” item. Whenever

possible, the criterion variables constructed in this way were then

summarised according to content and statistical criteria to form quasi

scales (“feature groups”). By summarising the individual features to

make quasi scales, each test person could be given a total score for

each quasi scale. The groups were then compared based on the total

scores. For the scale level of the quasi scales we adopted the ordinal

scale. After we had compiled the quasi scales according to content

critera, we carried out an item analysis to establish the legitimacy of

these post hoc compiled feature groups. As a measure of the inner

consistency, we calculated the selectivity (degree of separation) of the

individual features and as the form of the reliability analysis for each

quasi scale Alpha according to Cronbach. The statistical comparison

of the groups on the 14 point quasi scale was done with a ranking test

for ordinally-scaled variables (Chi2 – test as per van-der-Waerden)

on the 5 per cent significance level.

Results

Comparison of the three perpetrator groups regarding

biographical stress factors

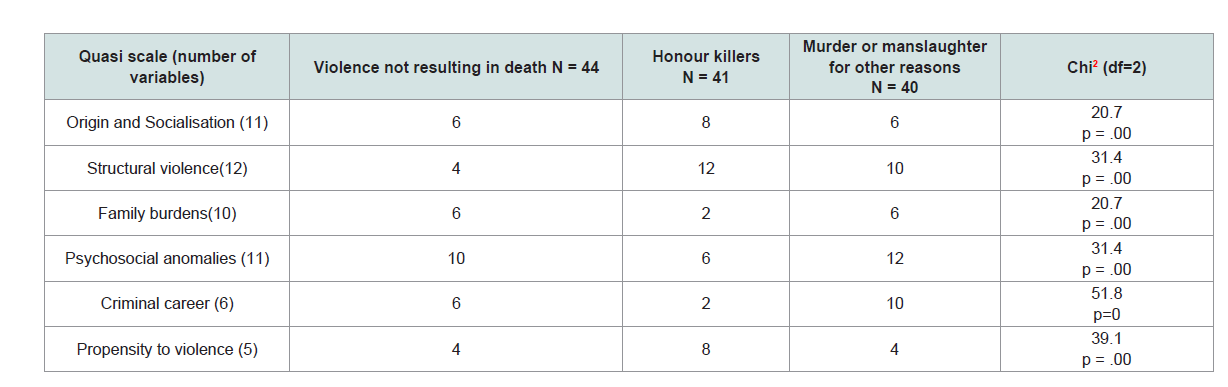

The ranking comparison regarding the accumulation of

biographical stress features led to a significant result in all three

groups investigated. The honour killers reported religious-patriarchal

notions to a significantly more frequent degree, saying that to uphold

and maintain honour had been at the centre of their upbringing

(recorded on the quasi scale Origin and Socialisation). At the same time, many of these test persons said they had experienced violence

at the hands of soldiers, the army, parents or teachers in their home

country (Table 4).

Table 4: Medians of thenumber of applicable features for the six scales on the perpetrators’ biographical features.

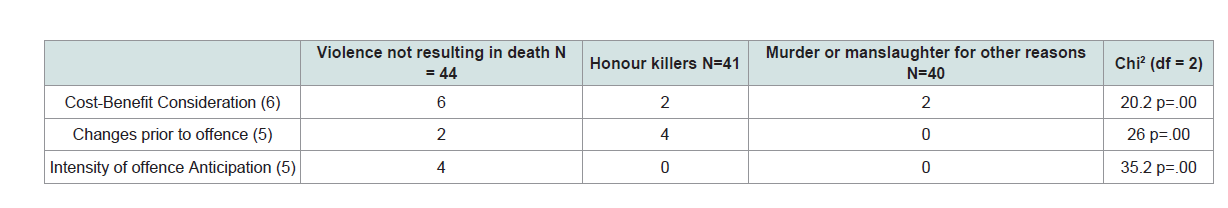

Table 5: Medians of the number of applicable features for the scale “cost-benefit consideration” and “intensity of offence anticipation”.

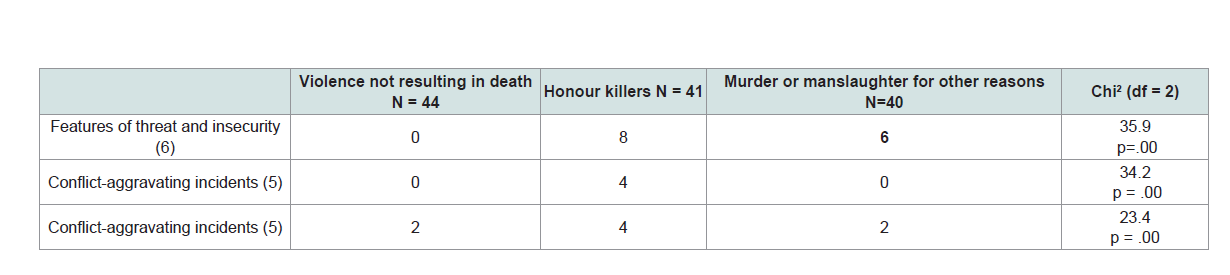

Table 6: Medians of the number of applicable features forscale 12 “conflict-aggravating incidents”, scale 13 “features of threat and insecurity” and scale 14 “disorder

in post-offence behaviour”.

Cognitive features, behavioural patterns and incidents preceding the offence:

The statistical comparison of the three perpetrator groups

regarding conflict-aggravating incidents and behaviour preceding

the offence led to significant results in respect of the scale cost-benefit

considerations, changes prior to the offence and intensity of offence

anticipation (Table 5). There were no significant results in respect of

alcohol and drug consumption preceding the offence and economic

deprivation.Threat and Insecurity:

The three perpetrator groups differed significantly regarding

conflict-aggravating incidents (Scale 12) in the pre-scene, features

of threat and insecurity(Scale 13) and disorder in post-offence

behaviour(Scale 14) (Table 6).Social Environment:

We also investigated reinforcement from the social environment.

Here there was a significant connection between the feature

reinforcement from the social environment and the scaleres toring

honour and structural violence (Table 7). Table 6: Medians of the number of applicable features for scale 12 “conflict-aggravating

incidents”, scale 13 “features of threat and insecurity” and scale 14

“disorder in post-offence behaviour”Discussion

The ranking comparisons for the accumulation of biographical

stress factors indicate that the three perpetrator groups were exposed

to varying degrees of unfavourable socialisation conditions. For the

group murder or manslaughter for other reasons severe stress was

prevalent in all the biographical areas under investigation. In contrast,

the group violence not resulting in death had the fewest biographical

stress factors. The honour killers revealed the highest degree of stress

above all in the case of structural violence. These test persons had

also had a strongly patriarchal-religious upbringing. The benefits

of restoring honour by means of the offence and thereby getting

recognition from the social group had a higher value than the risk of

being arrested and possibly being economically disadvantaged as a

result. The links between reinforcement from the social environment

and the scales restoration of honour and structural violence revealed

important effects. Increased unfavourable biographical peculiarities

in the case of the honour killers compared to other perpetrators

were not confirmed, since the perpetrators of violence not resulting

in death, especially when comparing family stress factors and the

features of their criminal career, also revealed high values. The

key to understanding perpetrators who kill somebody whom they believe has violated honour could possibly be found however in the

patriarchal-religious upbringing of those concerned together with

violence as an educative method in the broader society (school, army,

parents, war zone) in their country of origin. With regard to the

scales of weighing up the consequences (cost-benefit considerations)

and planning the crime (intensity of offence anticipation), the

results showed a division into two of the three perpetrator groups.

In the days and weeks before the crime the honour killers thought

more elaborately about their crime than the other two groups.

We assume that the collective contributes in a decisive way to the

crime in the case of a perceived violation of honour. The subsequent

perpetrator is much more preoccupied with the possible offence in

his environment and the discussion in the community regarding

violation and restoration of honour finally leads to the enaction

of the crime [43,44]. The group murder or manslaughter for other

reasons was also primarily concerned with the planning and possible

consequences, albeit significantly less than the honour killers. They

displayed a less emotional approach, weighed up various alternatives,

in some cases thought intensively about the risk of the crime and the

punishment and imagined the course of the act and any problems and

obstacles which might arise there from [45]. The group violence not

resulting in death thought less about the possible consequences of the

crime. These consequences hardly seemed to have been anticipated

and planned, but displayed the characteristics of a spontaneous

“impulsive act”. The less the course of the act was anticipated and

the less was thought about the cost-benefit aspect, the more likely it

was that, after the act, the perpetrator was reminded by unexpected

events later which made him insecure. From a theoretical point of

view this can be interpreted by the fact that the honour killers used

violence from the standpoint of an expected event and experienced

fewer target conflicts. Accordingly, the perpetrators behaved more

calmly and less chaotically after the act. In general we can, with care,

assume that crimes carried out on the basis of a perceived honour

violation lead to fewer situations of surprise from which further

acts of violence can develop [46]. It appears difficult to prevent such

acts since the perpetrators are in most cases directly related to the

victims and have shown hardly any criminal activity beforehand [47].

However, their strong patriarchal-religious perception of honour is

recognisable. It is important for advisors, police officers, physicians

and psychotherapists to take down an exact record of the case history

in its transcultural context duringany contact with advice centres,

in medical-psychological investigations or in a case where a person

affected reports the possible act to the police, prior to such a crime

being committed [48]. For instance, by means of a special interview

approach, the interviewer could ask questions to find out whether

there was a rigid family structure and about the importance of honour

for the family. Human rights organisations in the countries of origin

are unambiguously and strictly against any reduced or commuted

sentences for such perpetrators [49].

Conclusion

It shows that many prevention and support measures still need to

be taken to prevent honour crimes both in the countries of origin and in migration. Not only the possible perpetrators, but also society as a

whole must be involved, as they consciously or unconsciously create

social pressure and tolerate these acts. In this context, it is necessary

to change the traditional ideas of men, but also of women, which have

been shaped for centuries: It must be made clear that no religion or

tradition can justify crime in the name of honour. Only in a society in

which both sexes live together on equal terms are the conditions given

for crimes in the name of honour to be completely eliminated. Even

if the legal aspect of the guilt principle, which is free of culturalist

prejudices and simplifications, ensures that the same law applies

to everyone and that the perpetrators are punished appropriately,

the aspect of the crime as a violation of human rights must not be

forgotten.