Journal of Emergency Medicine & Critical Care

Download PDF

Review Article

Characteristics of the Contemporary Intensivist: A Qualitative Study

Dennis D1*, Knott C2, Khanna R3 and van Heerden PV4

1Department of Intensive Care and Physiotherapy Department, Sir Charles

Gairdner Hospital, Perth, Western Australia; Curtin University, Faculty

of Health Sciences, Perth, Western Australia

2Department of Intensive Care, Bendigo Health, Bendigo, Victoria, Australia;

Monash Rural Health Bendigo, Monash University, Victoria, Australia; Rural

Clinical School, University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Department of

Intensive Care, Austin Health, Heidelberg, Victoria, Australia

3Phoenix Australia, Department of Psychiatry, University of Melbourne,

Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Division of

Mental Health, Austin Health, Heidelberg, Victoria, Australia

4Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Hadassah

Medical Center and Faculty of Medicine, Hebrew University of Jerusalem,

Israel

*Address for Correspondence:

Dennis D, Intensive Care Unit, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Perth,

Australia; Senior Lecturer, Curtin University, Perth, Australia; E-mail:

Diane.Dennis@health.wa.gov.au

Submission: 10 June 2022

Accepted: 16 July 2022

Published: 23 July 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Dennis D, et al. This is an open access article

distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the

original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background: Intensive care professionals work together within a

high-acuity high-stress environment and develop unique clinical and

human skill sets within the specialty. The manner in which medical

leadership acts, responds, and is understood by those around them

is an important component of optimising healthcare. The aim of this

study was to explore, qualify and define the self-perceived attributes

of senior doctors working in intensive care (Intensivists), and construct

‘Intensivist personas’ that might provide useful insight for the entire

healthcare team.

Methods: Using a prospective qualitative design, this study

involved face-to-face interviews with 19 Intensivists who each had

more than four year’s clinical experience. Participants were asked

their perceptions of the typical personality traits of a ‘flourishing’

Intensivist; and how they felt they were viewed by others outside their

specialty. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed and attributes

were coded using a thematic framework analysis of each transcript

using NVivo software. Personas that might represent the contemporary

Intensivist were then constructed based on the themes that emerged.

Results: More than 700 pages of coded data were extracted from

the transcripts. Six personas were built according to how Intensivists

saw themselves: the Fixer; the Retriever; the Diplomat; the Negotiator;

the Pragmatist; and the Duck. An additional three personas were

created relating to how they perceived they were viewed by others’:

the Superhero; the Naysayer; and the Dictator.

Conclusion: This study describes the self-perceived personality

traits of modern-day Intensivists and in doing so, adds to the scarce

qualitative literature available. Understanding these attributes is

important for all who work in intensive care, including nurses who are

an integral part of healthcare service delivery.

Keywords

Intensive care medicine; Doctors; Thematic framework

analysis; Personality traits; Interview

Background

The practice of medicine goes back to ancient times and was

historically a broad-based science. In modern medicine, there is

increasing specialisation of practice in line with the massive expansion

of knowledge, and the advanced skill set required to deal with new

technology. As a result, our human understanding of ‘what it is to

be a doctor in the 21st Century (Common Era) is rapidly evolving,

with over 1.5 million new medical-related studies indexed annually

on search engines such as Pubmed [1].

Intensive care is a field of medicine devoted to managing complex

life-threatening illness. It has its origins in the mid-nineteenth century

Crimean War, when Florence Nightingale tended to those soldiers

worst injured in an area geographically closest to her nursing station.

These patients were closely monitored and attended to quickly in the

event of clinical deterioration [2]. This ‘collective’ model of acute

care (cohorting the sickest patients to where most of the resources

are) was further established in the 1950s in response to the global

poliomyelitis epidemic. Medical centres throughout the world

established respiratory ‘intensive care units’ (ICUs) to monitor and manage patients requiring positive and negative pressure ventilation.

Anaesthetists were frequently involved in the development of these

services as they were seen to be the experts in airway intubation

[2], ventilation and resuscitation. In the years that followed, these

respiratory or ‘general’ ICUs devolved into the distinct sub-specialties

seen today in some countries, based on the nature and case-mix of

the hospital. For example, separate ICUs for surgical, burns, cardiac,

paediatric and neonatal patients.

As the discipline of Intensive Care matured, specialist doctors from

other, often diverse, backgrounds also sub-specialised in intensive

care medicine. Part of this involved the establishment, development

and maturation of professional societies which defined the role of the

‘Intensivist’, including the core competencies and training required.

In Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand, the ‘newness’ of intensive

care medicine as a speciality is reflected by the fact that the Australian

and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS) first met in 1975

[3], formalising training of Intensivists in 1976 with a specialist

College becoming operational in December 2010 [4,5].

The key service elements of a modern general ICU are centred on

the delivery of a number of highly invasive supportive therapies such

as mechanical ventilation; renal replacement therapy; extracorporeal

membrane oxygenation and monitoring [6], which are implemented

through the coordination of a broad interprofessional team of

doctors, nurses, allied health professionals and others. Modern-day

Intensivists are correspondingly directly responsible for patients

under their care in a relatively closed clinical system, with input

from other specialties as required [4], the so-called “closed” model

of intensive care.

Although present-day doctors represent a similar cohort in

terms of the entrance criteria for medical school, and receive broadly similar pre-licensure training, there is an abundance of literature

dating back to the 1960s suggesting that personality stereotypes

exist for some medical specialties [7,8]. Anaesthesia, for example,

has been reported to attract people who are more self-sufficient and

extroverted compared to doctors in general practice [9]; Psychiatrists

have been characterised as possessing greater frustration tolerance,

emotional maturity and stability than seen in other fields [10];

Surgeons have been found to be more tough-minded, resolute and

unempathic compared to both anaesthetists and doctors in general

practice [11]. These data are important, as the synergy of personality

type with working environments has been shown to be significantly

related to workplace resilience [12].

A persona describes a particular type of character that a person

seems to have, often different from the real or private character that

person has [13]. It is a fictional individual whose characteristics

may be derived as a composite of a number of different real people

[14]. As the field of intensive care medicine is relatively new, there

is little published data related to the self-perceived personality traits

of doctors working in the domain. Creating a shared understanding

of these frames would be useful to all who work within the intensive

care healthcare service delivery. Based on the personal reflections of

a sample of Intensivists, the aim of this study was to explore, qualify

and define the attributes of doctors working in intensive care in order

to construct the persona or personas of the contemporary Intensivist.

Methods

Research design and setting:

This study used a prospective qualitative design to explore the

research question of what characteristics define the attributes of

doctors working in intensive care. To answer this, the primary

objectives were to1. Interview a group of experienced Intensivists

2. Analyse their responses and construct a persona or

personas of the ‘typical’ Intensivist.

A once-off face-to-face interview was conducted on-site at each

participant’s respective hospital during non-clinical time in a quiet

location adjacent to the ICU. Ethical approval was granted by Sir

Charles Gairdner Hospital HREC (Lead site: RGS0794); the Austin

Hospital/HREC/18/OTHER/14); Hadassah University Hospital

(0313-18HMO). All participants provided informed written consent

prior to participating in the study.

An example of the specific interview questions relating to

Intensivists’ perception of the characteristics of the modern-day

Intensivist was:

“Can you describe what you think are the attributes and typical

personality traits of a ‘flourishing’ Intensivist?”

and “How do you think those professionals outside of intensive

care view the stereotype of the contemporary Intensivist?”

Participants:

Intensivists from two countries (Australia and Israel) who had

worked in the ICU specialty for more than four years were considered

for inclusion in the study cohort. They were approached in-person by the site investigator and provided informed written consent prior to

participating.Data collection:

Data collection was undertaken by three researchers (Intensivists

[CK and PVvH], and non-Intensivist [DD]) who all had experience

in qualitative research methods. Interview data was audio-recorded

and transcribed. Transcripts were edited by participants for accuracy,

and then returned to one investigator (DD) who entered them into

the dataset as de-identifiable data. Data saturation was reached

after approximately 60% of the population of Intensivists had been

interviewed at the first site (in Israel), suggesting that approximately

15-18 participants would provide thematic sufficiency.Data analysis:

NVivo software (Version 12, 2018 software; QRS Pty Ltd.,

Victoria, Australia) was used to undertake a thematic framework

analysis. Codes were initially generated by two investigators (DD and

RK) who reviewed two random transcripts independently. One of

these researchers (RK) had not undertaken any interviews and was

not an Intensivist, which ensured the reflexivity of the analysis. The

final code-book was built with the consensus of all investigators who

subsequently coded all manuscripts. Personas were created from the

themes and subthemes that emerged from coding; literal quotations

were selected to support these constructs.Results

During 2018, 19 hour-long interviews were carried out at an

Israeli institution (n=6) and two Australian institutions (n= 6 and 7

respectively), with one Australian Intensivist declining to participate.

Six personas were constructed around the self-perceived attributes

that defined the Intensivist.

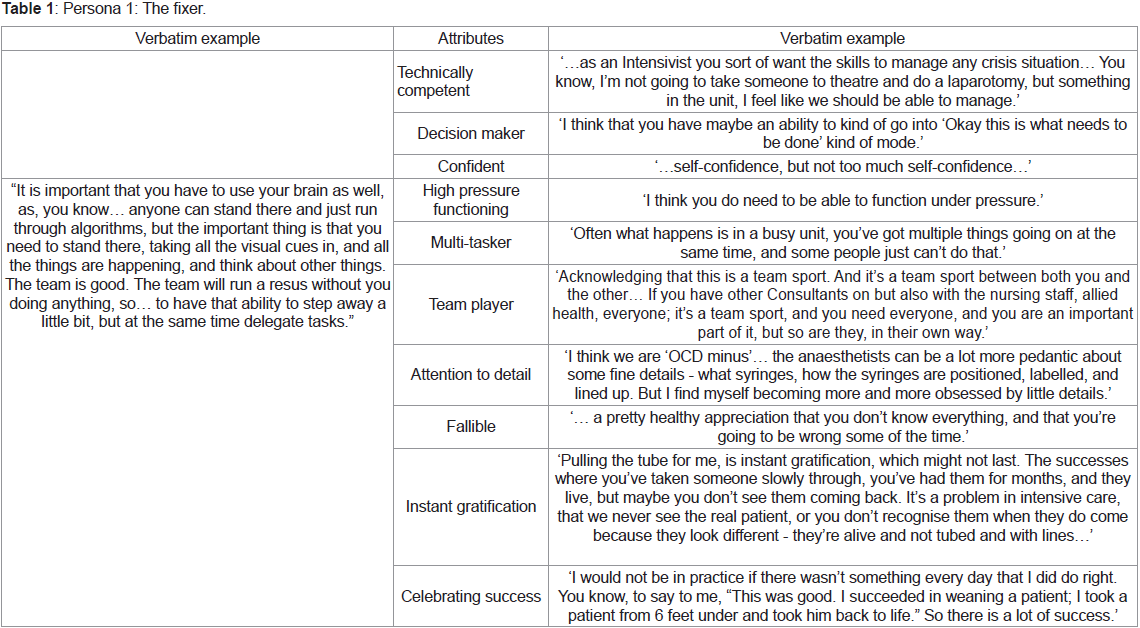

The Fixer (Table 1): Described as one who applied technical competence

to make patients better; someone confident who worked well

under pressure.

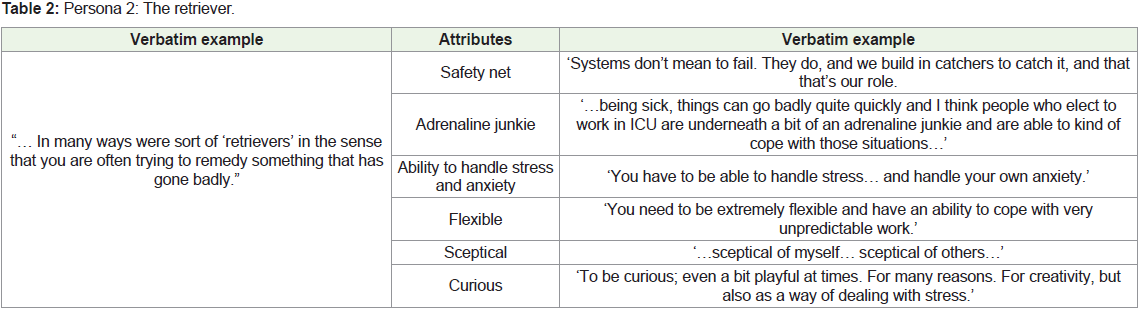

The Retriever (Table 2) : Described as one who was able to take

the sickest of patients and restore them to better health.

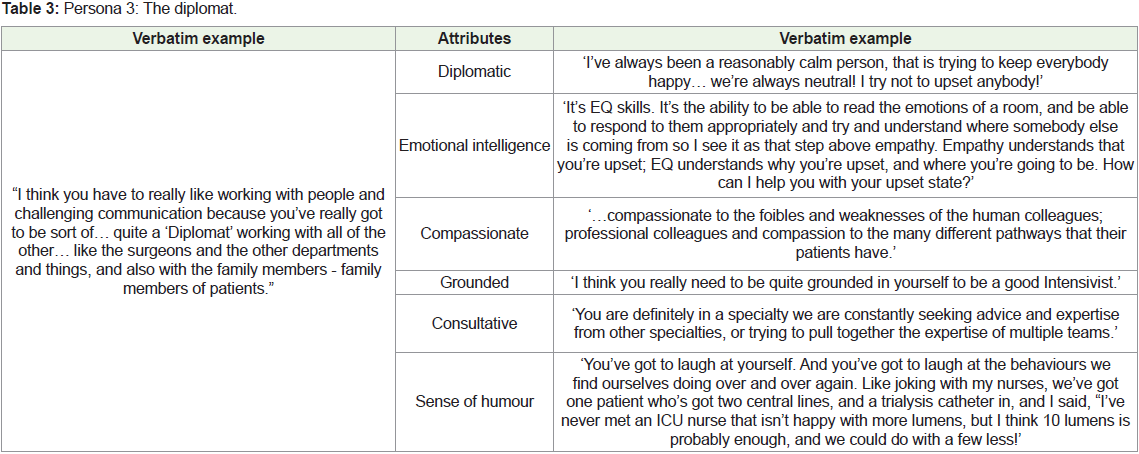

The Diplomat (Table 3): Described as one who was able to navigate

interpersonal relationships successfully in order to facilitate best

patient care.

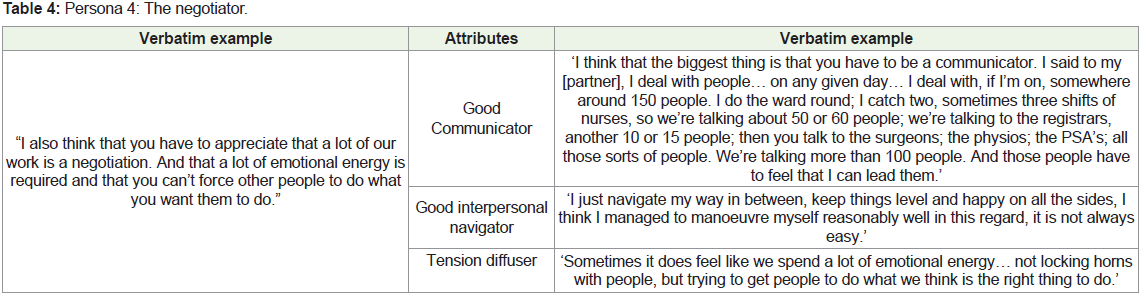

The Negotiator (Table 4): Described as one who was a steadfast

patient advocate in order to facilitate best patient care.

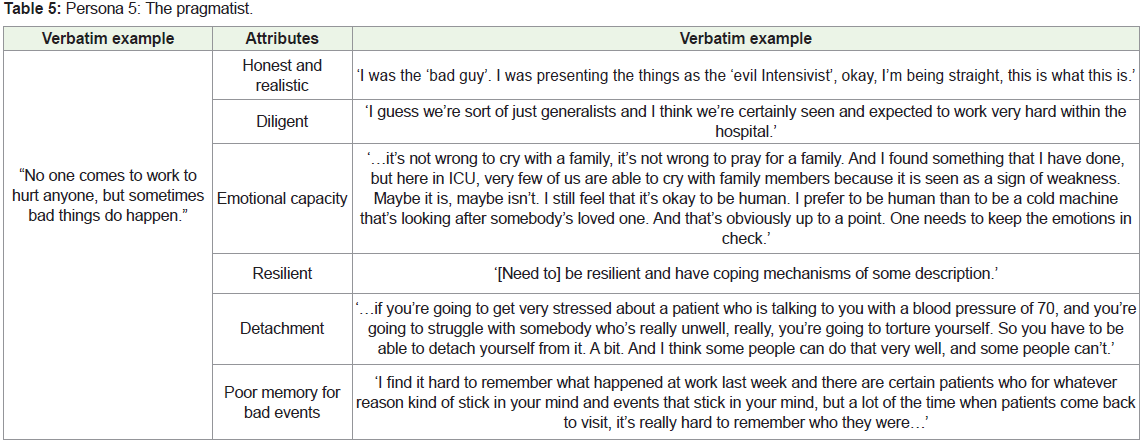

The Pragmatist (Table 5): Described as one who was realistic and

practical in the face of difficult conversations and uncertainty.

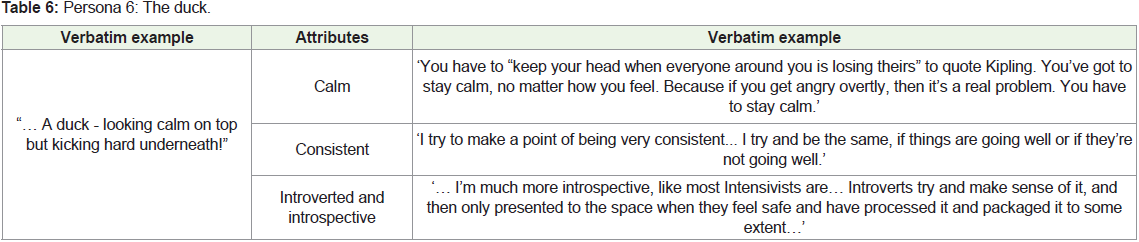

The Duck (Table 6): Described as one who appeared consistently

calm in a crisis whilst perhaps figuratively paddling furiously beneath

the water to achieve a good outcome.

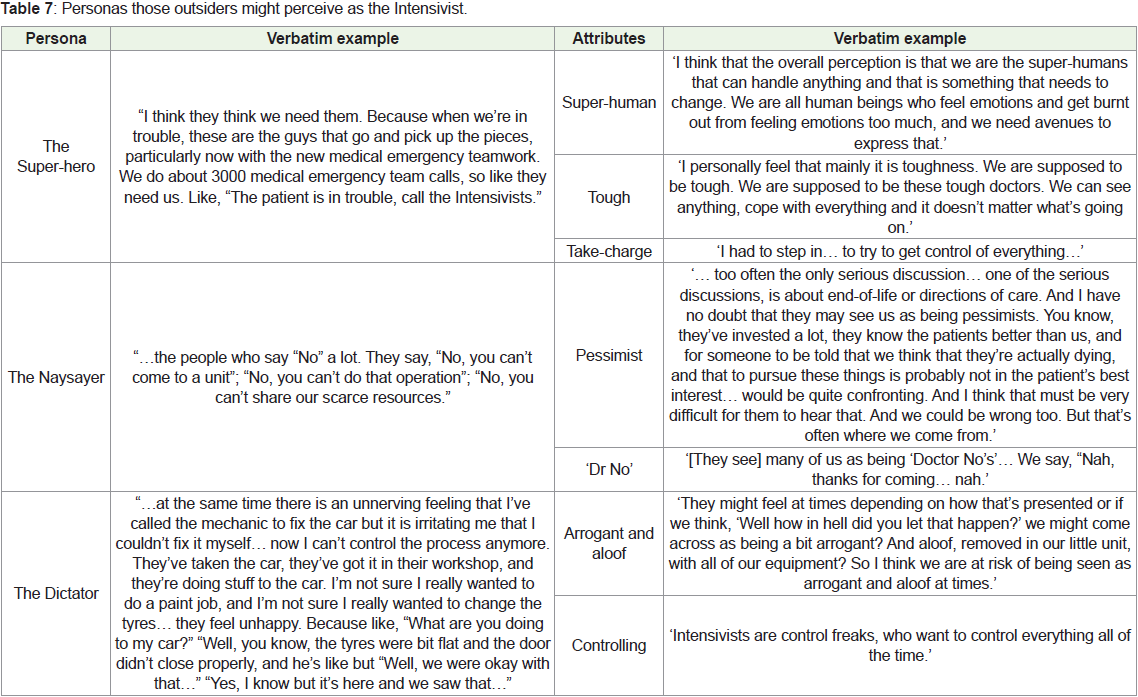

A further 3 personas were constructed around reported attributes

which the Intensivists considered were the external perception

of that outside of the Intensive Care Medicine specialty (Table 7). These were the Super-hero; the Naysayer; and the Dictator.

Discussion

Perceptions of self (Tables 1-6):

When asked to describe the attributes and typical personality

traits of a ‘flourishing’ Intensivist, one respondent began by saying,

“I think it takes all sorts” and this statement summarises the data

that emerged. We built nine personas from the attributes that

Intensivists’ identified, either within themselves or in their intensive

care colleagues. Six of these were constructed according to how

they viewed themselves; three were assembled in line with how they

imagined their specialty projected themselves outside of intensive

care.Intensive care doctors deal in high levels of patient illness acuity,

and each persona perhaps reflects a unique facet of their daily life,

including the responsibility of directing the provision of care. Intensivists are often leading a team as the last in a long line of defence

trying to enhance survival and recovery for a patient. Working with

their team, they may bring people back from the certainty of death

to the possibility of survival (the Retriever persona). We can conjure

up visions of care and consultation outside of the ICU, such as their

attendance at Medical Emergency Team calls, their involvement

in the triage of patients’ enroute from places external to hospital

emergency departments; or from within the hospital, like operating

theatres. Being both curious and sceptical of other’s decision making

fits the uncertainty of being faced with an unknown patient in an

unfamiliar non-ICU environment. It also allows for the avoidance of

cognitive biases in one’s own decision-making which is needed in

order to function as this last line of defence [15]. Being adaptable and

flexible in response to unexpected circumstances, in fact thriving in

that atmosphere, like an ‘adrenaline junkie’, were key components of

this persona.

Perhaps more optimistically, Intensivists also possess the

expertise and technological arsenal to lead new solutions in the high

acuity environment (the Fixer persona) to enhance patient survival

or improve prognosis. This persona comprised sound clinical

competence, strong technical skills with confidence and ability to

undertake multiple tasks and make quick decisions under high levels

of pressure.

Acknowledgment that the Intensivist does not function in

isolation was a key attribute of the Fixer, whereby teamwork, and the

ability to share in the celebration of success, were qualities identified.

The Intensivists recognized that they bring others along with

them on the patient’s journey, sometimes willingly (the Diplomat

persona) and sometimes under duress (the Negotiator persona).

The features of the Diplomat included an ability to ‘read the room’

in difficult circumstances and remain grounded and compassionate.

The Diplomat is happy to seek the advice of others, and able to

laugh at their own idiosyncrasies. The most distinctive attribute

of the Negotiator is the skill of communicating, and the ability to

navigate and overcome interpersonal conflict and diffuse tension.

This extended from interactions with co-workers in the ICU to

interactions with patients, and family, and the other specialties with

whom they worked.

Respondents commonly acknowledged that no matter how much

quality care they provide, patients can still unpredictably live or die

without rationalisation. The Pragmatist persona comprised those

attributes of honesty, diligence and realism, which aligned with an

ability to have a degree of detachment from emotional involvement

and a poor memory for bad events.

Finally, at their best, Intensivists bestow both their care and

training of others in a calm and consistent manner (the Duck). This

persona represented more the manner in which they approached

their craft rather than the craft itself. The analogy was that during

crises, the Intensivist delivered coordinated care effortlessly as they

glided across the water, and yet beneath the water, they were actually

furiously paddling away. There is perhaps a piece of the Duck persona

in each of the other personas.

Projected perceptions of others (Table 7):

At face value, the projected perceptions of others looking in at

the specialty were somewhat at odds to the perceptions Intensivists

had of themselves. On closer examination however, each of the three

external personas could be seen as being equal and opposite to the

other six self-perceived constructs, albeit viewed in somewhat of

a negative light. For example, the ‘Super-hero’ Intensivist is seen

to swoop in when a patient or colleague is in peril to save the day

with super-human knowledge, calmness and strength of character

that belies authority. These features might be equally represented as

positive attributes in the characterisations of the Retriever and the

Duck - although the weight of responsibility that the Super-hero

persona conjures up perhaps matches the burden of the unreasonable

expectations placed upon them by others.Likewise, characteristics of the Pragmatist in taking a realistic

negative appraisal of the long-term outlook of patient care, and

relaying these views honestly with a level of personal detachment and

resilience, might be interpreted as reflecting a Naysayer persona - the

interpretation of what is pessimistic versus what is realistic defining the difference between the perspectives. The wide-angle lens of the Fixer

affords a longitudinal view and broad oversight and understanding

that might be viewed as arrogance in the ‘Dictator’ persona. Likewise,

the emotional intelligence and skill in communicating, seen in the

Diplomat and Negotiator respectively, might be represented in the

Dictator with negative connotation as being aloof and controlling.

It remains unclear as to whether these described perceptions

were derived from the responses Intensivists encountered in their

present-day practice, or whether they were anecdotally derived from

their years-in-training. No data was collected from people outside of

the specialty to support or refute the perceptions held, including the

nurses they worked with, as this was beyond the scope of the study.

With emerging literature related to the high rate of burnout

within the intensive care domain [16-18], our findings have

important implications in terms of the selection of, and entry into,

the specialty by medical trainees. Before choosing the intensive care

pathway, junior doctors should reflect deeply around their personal

attributes as to whether they fit some of the personae described.

Equally as important, during the selection of their trainees, training

programmes should screen applicants for attributes accordingly. It

should be acknowledged that some of these attributes, though not

directly teachable, can nonetheless be deliberately cultivated so may

have relevance even for current trainees/Intensivists. By having

awareness of the cultural traits in senior Intensivists, it may also be

desirable to select trainees differently for the creation of different or

diverse future personae for Intensivists who continue to adapt to the

ever-evolving sociotechnical field of intensive care medicine.

A strength of this study was that it sampled doctors from 3 sites

in 2 countries who had been working in the field of Intensive care

for a substantial length of time. Although some of those interviewed

serviced rural areas as ‘retrievalists’, a limitation was that the study

cohort was predominantly from urban adult intensive care centres

within well-developed healthcare service delivery teams. We

acknowledge that other personas and attributes may have surfaced

from a sample that included both rural and paediatric Intensivists.

There were also no interviews of people external to the specialty to

substantiate the perceptions had by those outside the discipline as to

the personas of the Intensivists, and this is both a limitation and a

path for further study.

Conclusion

This study adds to the relatively scarce qualitative literature on

the personality traits of doctors in modern-day medicine, providing

specific self-reported insight into the intensive care specialty. Nine

personas were constructed, and no one of these stood alone as

the ultimate definitive identity; neither was one specific persona necessarily mutually exclusive of another. The contemporary view of

the Intensivist is perhaps better represented as a combination of all

of the nine described. The perception of others working in the field

related to these personas is a future direction of this work.

References

3. Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS) (2021) Our History Camberwell, Victoria.