Journal of Clinical and Investigative Dermatology

Download PDF

Case Report

A Case of Leukemia Cutis in A 43-Year-Old Male with Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia

Caryl Lyca M. Dematawaran*, Ma. Flordeliz Abad-Casintahan and Elisa Rae L. Coo

Department of Dermatology, Jose R. Reyes Memorial Medical Center, Manila, Philippines

*Address for Correspondence:Caryl Lyca M. Dematawaran, Department of Dermatology, Jose

R. Reyes Memorial Medical Center Manila, Philippines. E-mail Id: clmdematawaran@gmail.com

Submission: 13 September, 2025

Accepted: 07 October, 2025

Published:10 October, 2025

Copyright: © 2025 Dematawaran CLM, et al. This is an

open access article distributed under the Creative Commons

Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution,

and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is

properly cited.

Keywords:Leukemia Cutis; Chronic Myeloid Leukemia; Chronic

Myelogenous Leukemia

Abstract

Leukemia cutis is a dermatological condition characterized by

the infiltration of leukemic cells into the skin. It manifests as various

skin lesions such as macules, papules, plaques, or nodules, commonly

appearing on the trunk, extremities, or head. The condition is

uncommon in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), occurring far

less frequently than in acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), where

it is reported in about 10–15% of cases. In this report, we present a

compelling case of a 43-year-old male with chronic myelogenous

leukemia who developed leukemia cutis. The emergence of leukemia

cutis serves as an indicator of disease progression and is associated

with a generally poor prognosis. Our objectives are to report a case

of leukemia cutis in a CML patient and to compare this patient to

the existing literature on the clinical manifestations, management

strategies, and disease outcomes specific to leukemia cutis in the

context of CML. By reviewing the available information, we aim to

enhance our understanding of this condition and provide valuable

insights into its diagnosis and treatment.

Introduction

Leukemia cutis refers to the infiltration of leukemic cells into

the skin.[1] It commonly manifests on the trunk, extremities, and

head as solitary or multiple macules, papules, plaques, and nodules.

[2,3] In rare cases, the lesions present as blisters and ulcers.[3] This

condition can occur in various types of leukemia, more commonly

in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or acute lymphoblastic leukemia

(ALL).[2] In chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), leukemia cutis

is a relatively rare manifestation. It is estimated that leukemia cutis

develops in 10-15% of patients with AML and is less frequent in CML.

[2,3] Leukemia cutis can occur at different stages of CML, including

the chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase. However, it is

more commonly observed in the blast phase, which is characterized

by more aggressive disease features and increased infiltration of

leukemic cells into extramedullary sites.[4] Certain factors may

increase the likelihood of developing leukemia cutis in CML. These

include a higher disease burden, advanced disease phase, specific

genetic mutations, and resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors

commonly used in CML treatment.[5]

This report will present a case of leukemia cutis which rarely presents in chronic myelogenous leukemia.

This report will present a case of leukemia cutis which rarely presents in chronic myelogenous leukemia.

Case Report

A 43-year-old, male, married, Filipino security guard, known case

of CML, presented to the clinic with an 8-week history of gradually

increasing non-pruritic, non-painful, erythematous papules and

plaques on the trunk and bilateral upper and lower extremities. There

was no associated discharge or bleeding. He denied history of trauma

or manipulation. There was no change in personal products used. No

medications were applied.

Two years prior, the patient was diagnosed with CML at another

institution through bone marrow aspiration and core biopsy. He

was initially managed with imatinib mesylate 400 mg once daily

for 11 months with good response. No drug sensitivity testing

was performed prior to initiation of imatinib, as this is not readily

available in our setting. One year prior, he was admitted due to anemia

and thrombocytopenia which were attributed as complications of

imatinib. Hence, imatinib was decreased to 100 mg once daily. He

was also maintained on prednisone 20 mg once daily, ferrous sulfate

325 mg once daily, and folic acid 5 mg once daily. Upon initial

consultation at the dermatology clinic, he reported discontinuation

of imatinib intake for two months due to the lack of funds.

The patient has no known history of other comorbidities nor prior

surgeries. He has a family history of hypertension on the paternal side

and asthma on the maternal side. He has no family members with the

same lesions. The review of systems was unremarkable.

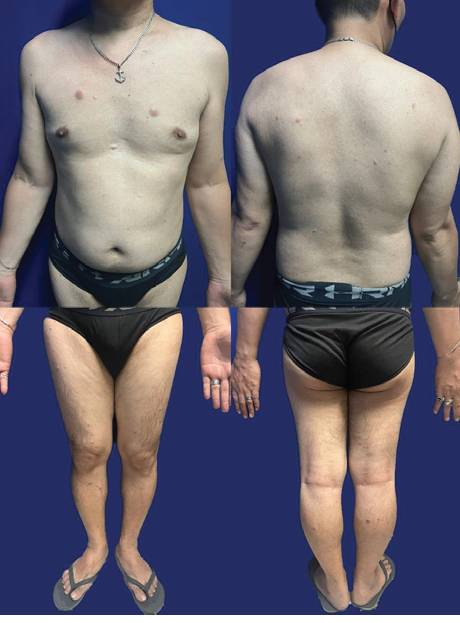

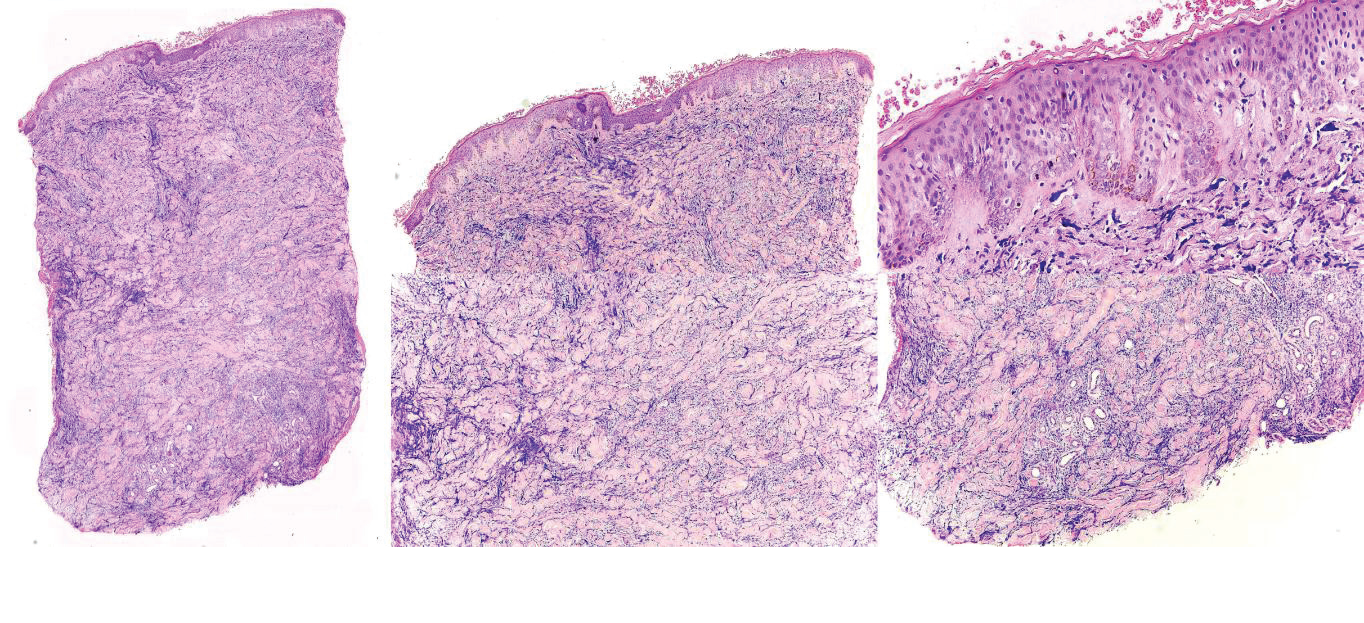

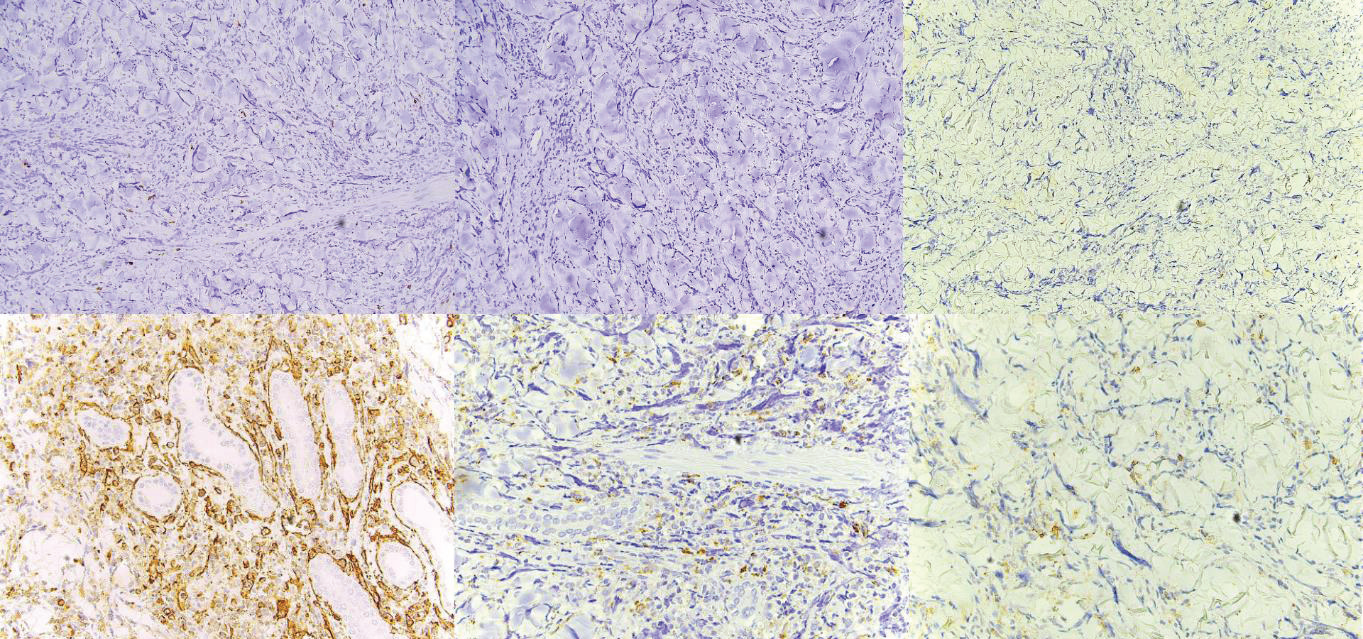

On dermatologic examination, the patient presented with multiple, discrete, round, firm, erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques on the chest, back, and bilateral upper and lower extremities [Figure 1]. The initial clinical differential diagnoses were leukemia cutis, erythema nodosum, fixed drug eruption, arthropod bite reaction, and allergic contact dermatitis. He underwent a 4 mm skin punch biopsy on the chest. Haematoxylin and Eosin-stained sections revealed orthokeratosis, and an acanthotic epidermis that was slightly papillomatous with basal layer hyperpigmentation. In the dermis are diffuse infiltrates of atypical leukemic and myeloblastic cells in between thickened collagen bundles as well as surrounding adnexal structures and neurovascular bundles. [Figure 2]. The specimen was negative for CD3, CD20, Myeloperoxidase (MPO), and CD117 [Figure 3A-D]. Meanwhile, it was positive for CD34 and CD68 (Figure 3E, Figure 3F). The histopathologic examination and immunohistochemical staining were consistent with leukemia cutis.

He was advised to continue his intake of imatinib 100 mg once daily. He then reported a decrease in the number of the lesions and

On dermatologic examination, the patient presented with multiple, discrete, round, firm, erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques on the chest, back, and bilateral upper and lower extremities [Figure 1]. The initial clinical differential diagnoses were leukemia cutis, erythema nodosum, fixed drug eruption, arthropod bite reaction, and allergic contact dermatitis. He underwent a 4 mm skin punch biopsy on the chest. Haematoxylin and Eosin-stained sections revealed orthokeratosis, and an acanthotic epidermis that was slightly papillomatous with basal layer hyperpigmentation. In the dermis are diffuse infiltrates of atypical leukemic and myeloblastic cells in between thickened collagen bundles as well as surrounding adnexal structures and neurovascular bundles. [Figure 2]. The specimen was negative for CD3, CD20, Myeloperoxidase (MPO), and CD117 [Figure 3A-D]. Meanwhile, it was positive for CD34 and CD68 (Figure 3E, Figure 3F). The histopathologic examination and immunohistochemical staining were consistent with leukemia cutis.

He was advised to continue his intake of imatinib 100 mg once daily. He then reported a decrease in the number of the lesions and

Figure 1:Dermatologic examination upon initial consultation revealed

multiple, discrete, round, firm, erythematous to violaceous papules and

plaques on the chest, back, and bilateral upper and lower extremities.

Figure 2: Haematoxylin and Eosin-stained sections. A. Pathology in the entire

dermis (scanning magnification). B. The epidermis is acanthotic and slightly

papillomatous with basal layer hyperpigmentation (10X magnification). C. The

stratum corneum is orthokeratotic. Grenz zone is noted (40X magnification).

D. In the dermis are diffuse infiltrates of atypical leukemic and myeloblastic

cells in between thickened collagen bundles (10x magnification). E.

Surrounding adnexal structures and neurovascular bundles are appreciated

(10x magnification).

Figure 3:Immunohistochemistry Staining. A. CD3 negative. B. CD20 negative.

C. MPO negative. D. CD117 negative. E. CD34 positive. F. CD68 positive.

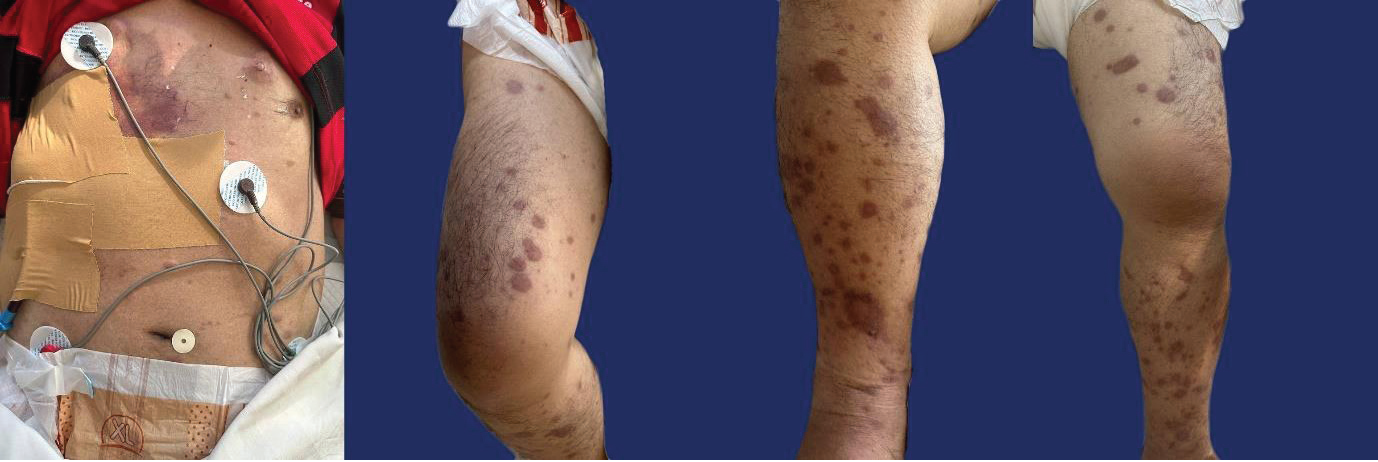

flattening of the remaining lesions. However, two months after, he

was admitted due to easy fatigability. There was an increase in the

number of lesions, especially on the back and lower extremities

[Figure 4]. Complete blood count showed anemia, leukocytosis, and

thrombocytopenia. Thoracic ultrasound revealed bilateral pleural

effusion. One day after referral to the dermatology service, the patient

expired due to hypovolemic shock secondary to massive blood loss.

The main service was not able to rule out a cerebrovascular bleed

since cranial imaging was not done.

Discussion

Leukemia cutis is defined as the cutaneous invasion of malignant

hematopoietic cells. The clinical lesions are usually multiple and

asymptomatic. [6,7,8] These may appear violaceous, red-brown, or

hemorrhagic.[2] The lesions more commonly present as macules,

papules, plaques, and nodules. [2,3] Rarely, these may also manifest

as erythema, erythroderma, ulcers, and blisters. [6,7] The usual

sites of predilection include the trunk, extremities, and head. When

present in the face, nodular and plaque lesions may resemble leonine

facies.[3] When the predominant lesions are nodules and papules,

these are more frequently firm, dome-shaped lesions.[8] The lesions

of leukemia cutis have a predilection to erupt at sites of previous or

current inflammation.[2] It is also worth noting that, even in the

same patient, leukemia cutis may produce various lesions during the

course of the disease. [2] The patient in this report manifested with

a common presentation of the disease, specifically multiple, papules

and plaques on the trunk and extremities. However, if the patient was

not initially diagnosed with CML, leukemia cutis would not be the

initial impression in this case as the lesions of leukemia cutis mimic

multiple disease entities. This highlights the importance of completely

examining the patient even during the initial consultation.

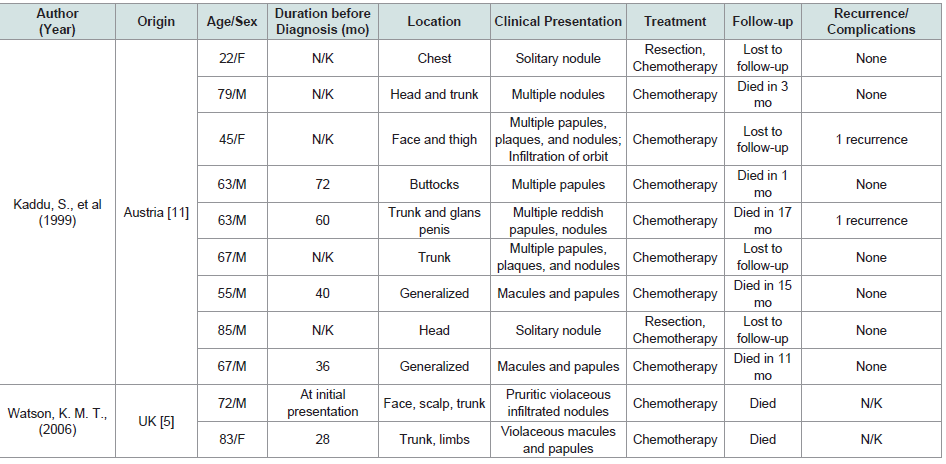

A review of the literature revealed 11 CML patients with leukemia

cutis (Appendix A). Most of the patients were elderly male patients.

Five of the patients were diagnosed with leukemia cutis more than

one year from the initial diagnosis of CML. Meanwhile, one patient

was diagnosed with leukemia cutis concurrently with CML. Majority

had lesions on the head, trunk, and extremities. Two patients had

generalized lesions. One patient only presented with lesions on the

buttocks; meanwhile, one patient had lesions on the glans penis aside

from the trunk. Multiple macules, papules, and nodules were the most

common primary lesions. All patients received chemotherapy and

two of them also had resection since they both had solitary nodule.

Seven of the patients expired with five of them expiring within two

years from the diagnosis of leukemia cutis. Only two patients had

recurrence of cutaneous lesions.

Review of the records at the Jose R. Reyes Memorial Medical

Center Department of Dermatology revealed two cases of leukemia

cutis, diagnosed in 2014 and 2016. Meanwhile, records of the

Philippine Dermatological Society – Health Information System

showed only two cases of leukemia cutis, diagnosed in 2015 and 2016.

[9] The low incidence of leukemia cutis from the records may not be

reflective of the true incidence of the illness in the country. This is

because only hospitals accredited with the Philippine Dermatological

Society are able to input to the database.

Table 1:APPENDIX A: Review of the demographic profile, duration before the diagnosis of leukemia cutis, clinical presentation, management, and complications of CML patients with leukemia cutis.

In most cases, the diagnosis of leukemia cutis is established after

the diagnosis of systemic leukemia.[3] There are few cases, however,

that the diagnosis is confirmed the same time as the systemic leukemia

or even before it – also known as aleukemic leukemia cutis.[2] Most

studies revealed that the mean interval from the diagnosis of systemic

leukemia to skin eruption is about one to two years.[10] Similarly,

our patient presented with cutaneous lesions two years after the initial

diagnosis of CML.

The diagnosis of leukemia cutis can be particularly complex. In some cases, patients may exhibit macular and papular eruptions that resemble drug or viral exanthem, while others may only present with a single nodule that shares clinical similarities with various conditions. Additionally, there are instances where patients manifest with aleukemic leukemia cutis. These scenarios underscore the critical significance of obtaining a histopathologic diagnosis to accurately identify and differentiate the condition.[11] Additionally, whenever appropriate, immunohistochemical staining would greatly help in the final diagnosis.

The diagnosis of leukemia cutis can be particularly complex. In some cases, patients may exhibit macular and papular eruptions that resemble drug or viral exanthem, while others may only present with a single nodule that shares clinical similarities with various conditions. Additionally, there are instances where patients manifest with aleukemic leukemia cutis. These scenarios underscore the critical significance of obtaining a histopathologic diagnosis to accurately identify and differentiate the condition.[11] Additionally, whenever appropriate, immunohistochemical staining would greatly help in the final diagnosis.

The histopathologic manifestation of leukemia cutis is

characterized by nodular infiltration of neoplastic leukocytes with

a perivascular-periadnexal distribution, or it may be interstitial

and diffuse. Epidermotropism is not common. The predominant

cell components are myeloblasts and granulocytic precursors.

The characteristics of neoplastic cells are large, with abundance of

eosinophilic cytoplasm, large nuclei with finely dispersed chromatin,

and occasional small nucleoli. There is also the presence of mitotic

figures as well as scattered macrophages and mature granulocytes.

The nerves, sebaceous glands, and muscle bundles are usually focally

destroyed.[2]

Based on the algorithm proposed by Cronin, et al. for diagnosing

myeloid leukemia cutis, the initial immunohistochemical stains to

be performed are CD3 and CD20 [12]. These markers are typically

negative in myeloid leukemia cutis, which aligns with the findings

in this patient’s case. The subsequent recommended stain is CD43,

which tends to be positive in nearly all cases of myeloid leukemia

cutis. However, this stain was not conducted in this case. The status

of MPO staining can vary, being either positive or negative in myeloid

leukemia cutis. In instances where it is negative, as observed in this

patient, CD68 may be requested. CD68 is generally positive in cases

of myeloid leukemia cutis. In line with this, the CD68 result in this

patient was indeed positive. Subsequently, CD56 may have been

considered. Similar to MPO, CD56 can be positive or negative. When

CD56 is negative, CD117 might be requested, and a negative result

would be indicative of myeloid leukemia cutis. Notably, this pattern

is consistent with the results in this case. It is worth mentioning that

the algorithm does not include CD34. A positive CD34 result suggests

the presence of myeloid or monocytoid leukemia cutis, specifically

granulocytic sarcoma. This outcome aligns with the observations in

this patient’s case.

The mechanism by which leukemic cells invade the skin remains

poorly understood. Cho-Vega, et al. proposed that leukemic cells

migrate into the skin tissue based on the skin’s affinity to attract

memory T-cells.[2] This theory emphasizes the potential involvement

of adhesion molecules, chemokines, and integrins in the process of

cell migration. Additionally, certain environmental factors such

as benzene exposure, chemotherapy drugs with alkylating agents,

ionizing radiation, and viral infections (e.g., HTLV-I infection

causing ATLL) pose similar risk factors for both systemic leukemia

and the development of leukemia cutis.[2]

Leukemia cutis is a manifestation of a systemic disease; hence, the treatment of the underlying leukemia using systemic chemotherapy is the main goal.[2,7] Kaddu, et al. demonstrated that patients who started chemotherapy showed remission of leukemia cutis and absence of recurrences.[11] However, they noted that most of the patients died within 12 months due to leukemia-related causes.[11] On the other hand, Watson, et al. noted that leukemia cutis was refractory to therapy and the benefits are usually short-lived.[5] In the case of the patient in this report, he noted an initial improvement of the lesions when he was restarted on imatinib. However, he reported progression of the lesions as he developed complications of CML.

Leukemia cutis is a manifestation of a systemic disease; hence, the treatment of the underlying leukemia using systemic chemotherapy is the main goal.[2,7] Kaddu, et al. demonstrated that patients who started chemotherapy showed remission of leukemia cutis and absence of recurrences.[11] However, they noted that most of the patients died within 12 months due to leukemia-related causes.[11] On the other hand, Watson, et al. noted that leukemia cutis was refractory to therapy and the benefits are usually short-lived.[5] In the case of the patient in this report, he noted an initial improvement of the lesions when he was restarted on imatinib. However, he reported progression of the lesions as he developed complications of CML.

Patients with leukemia cutis usually develop various

complications. However, these complications are commonly due to

the underlying leukemia instead of cutaneous lesions. Patients with

leukemia have pancytopenia so they are at risk for opportunistic

infections. They are also prone to bleeding due to thrombocytopenia

or, in some cases, due to the erosion of the skin lesions. Close

monitoring of systemic symptoms and serial laboratory examination

specifically complete blood count, bleeding parameters, and chest

radiographs are invaluable in detecting these complications. Other

complications include drug reaction to chemotherapy and mass

effect if the leukemia cutis presents as a tumor. [13] The patient in

this case developed easy fatigability most likely due to the anemia. He

also presented with leukocytosis hinting at a concomitant infection

as well as a probable cerebrovascular bleed due to thrombocytopenia.

All these complications are attributable to the patient’s CML.

The presence of leukemia cutis in CML is generally associated

with an unfavorable prognosis. It may indicate disease progression,

resistance to therapy, or transformation to a more aggressive form of

leukemia. [2,3] The survival of patients with leukemia cutis is short.

Chang, et al. observed that the mean interval between the diagnosis of

leukemia cutis and death was around eight months.[10] Meanwhile,

Su, et al. noted that 88% of patients die within one year of diagnosis.

[13] Watson, et al. reported that some patients with CML die within

three months from the eruption of the lesions.[5] Development of

leukemia cutis in CML is associated with transformation into the

blast phase, suggesting disease progression.[14] According to the

World Health Organization, one of the defining criteria for the blast

phase of CML is the presence of extramedullary blastic infiltration in

any organ or tissue, including the skin, where it manifests as leukemia

cutis. This occurs because of the presence of at least 20% blasts in the

peripheral blood and/or bone marrow, some of which may infiltrate

the skin.[15] In this report, the patient expired due to hypovolemic

shock secondary to massive blood loss with a possible cerebrovascular

bleed in a span of two months from the development of the lesions.

Conclusion

Leukemia cutis is a relatively rare manifestation of CML. It

typically appears as macules, papules, plaques, or nodules on

the trunk, extremities, or head. The diverse range of possible

morphologies can often make it challenging to differentiate from

other diseases. Therefore, a comprehensive investigation is crucial

to accurately diagnose this condition. Histopathologic examination

and immunohistochemical staining are valuable techniques used to

aid in the diagnosis. It is important to note that the development of

these skin lesions indicates disease progression and is associated with

a poor prognosis.

While chemotherapy can lead to the resolution of leukemia cutis, it is unfortunate that many patients still experience a shortened lifespan due to the complications associated with CML. These complications contribute to a reduced survival outcome for the affected individuals. Regardless of the aggressive treatment of the complications of CML, the diagnosis of leukemia cutis would inevitably lead to death. Hence, an extensive dermatologic examination of patients with CML is significant for an early diagnosis of leukemia cutis and prompt treatment of the underlying leukemia.

While chemotherapy can lead to the resolution of leukemia cutis, it is unfortunate that many patients still experience a shortened lifespan due to the complications associated with CML. These complications contribute to a reduced survival outcome for the affected individuals. Regardless of the aggressive treatment of the complications of CML, the diagnosis of leukemia cutis would inevitably lead to death. Hence, an extensive dermatologic examination of patients with CML is significant for an early diagnosis of leukemia cutis and prompt treatment of the underlying leukemia.

Ethical Considerations:

The patient’s legal guardian in this manuscript have given written

informed consent to publication of his case details.