Journal of Pediatrics & Child Care

Download PDF

Case Report

*Address for Correspondence: Michelle Steltzer, Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, CPNP-AC/PC, 4930 North Ardmore Avenue, Whitefish Bay, WI 53217, USA, Tel: 262-227-4569; E-mail: steltzer40@gmail.com

Citation: Steltzer M. Lifetime Impact of Congenital Heart Disease on a Family from the Perspective of a Third in Birth Order Sibling. J Pediatr Child Care.2016;2(1): 10.

Copyright © 2016 Steltzer. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Pediatrics & Child Care | ISSN: 2380-0534 | Volume: 2, Issue: 1

Submission: 11 January, 2016 | Accepted: 21 January, 2016 | Published: 27 January, 2016

Reviewed & Approved by: Dr. Ziad Albahri, Department of Pediatrics, Charles University, Prague Faculty of Medicine, Czech Republic

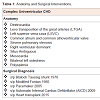

Any one of these diagnosis labeled in Table 1 can be difficult to process in isolation and impact on health. Imagine to yourself how you describe this diagnosis to any lay person, parent, sibling, or family member. How do you pronounce these large medical terms much less define them? What does it mean clinically? In our family, it became known that there was a “very rare single ventricle disease” present that required unusual reorganization of my brother’s cardiac “plumbing” to keep blood flowing well to the body and all essential organs to sustain life.

In 1970 a practicing general surgeon also certified in thoracic surgery, performed a Blalock-Taussig Shunt for my brother and was discharged 3 weeks later with a healing full thoracotomy. Limited open sleeping space available in the hospital hallways was utilized by my parents. They took turns traveling back and forth supporting the family back home and recovering second born son’s needs.

In retrospect, many fears and mystery surrounding my brother’s hospitalization were present. I had no concept of what a chest tube was or what it meant to be hospitalized after open heart surgery. My parents spoke of “drainage tubes” but what was that? As a visual learner, I suspect my fears and anxieties could have been reassured with a thoughtful health care provider and physical presence at the bedside. Today, there are many more educational resources and providers such as: nursing educators, practitioners, child life specialists, and social workers trained to facilitate families through the process of a hospitalization.

The natural milestones of my young adult life include: daughter, sibling, wife, mother, aunt, godmother, and nurse practitioner. As time went by, there were many milestones of adulthood shared with my brother and family. As his health failed, the anxiety, fear, and worry about his quality of life and survival grew. Having solid mentors and health care leaders within CHD to talk through these risks and benefits openly and honestly at every step of the way helped immensely to solidify the reality of the situation for me as a sibling and nurse.

In 2013, our family relocated back to the Midwest due to my husband’s job advancement. Primary focus during this transition time was on my nuclear family (husband, daughter, and son), extended family, self-care, and volunteering. My daughter was finishing her final year at a new high school and son entering middle school. One year later in the fall of 2014, my brother was chronically hospitalized awaiting heart transplant. Regular visits to support quality of life were important to continue our sibling relationship. My daughter continued her relationship with her uncle by attending many of these visits. My daughter is now a sophomore in college with an interest in the life science space. My son is finishing up eighth grade and active in extracurricular sports and music activities. Both are thriving. Unfortunately, my brother’s outcome was not as our family had dreamed and never left the hospital alive secondary to co-morbid issues. He died a few weeks following his 47th birthday and will now be forever in my heart. I am truly grateful for the 45 years I had with him as a sister. Learning about and dealing with sibling grief was the next personal challenge to navigate.

Lifetime Impact of Congenital Heart Disease on a Family from the Perspective of a Third in Birth Order Sibling

Michelle Steltzer*

- Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, CPNP-AC/PC, 4930 North Ardmore Avenue, Whitefish Bay, WI 53217, USA

*Address for Correspondence: Michelle Steltzer, Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, CPNP-AC/PC, 4930 North Ardmore Avenue, Whitefish Bay, WI 53217, USA, Tel: 262-227-4569; E-mail: steltzer40@gmail.com

Citation: Steltzer M. Lifetime Impact of Congenital Heart Disease on a Family from the Perspective of a Third in Birth Order Sibling. J Pediatr Child Care.2016;2(1): 10.

Copyright © 2016 Steltzer. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Pediatrics & Child Care | ISSN: 2380-0534 | Volume: 2, Issue: 1

Submission: 11 January, 2016 | Accepted: 21 January, 2016 | Published: 27 January, 2016

Reviewed & Approved by: Dr. Ziad Albahri, Department of Pediatrics, Charles University, Prague Faculty of Medicine, Czech Republic

Abstract

Background: Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the number one birth defect reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [1]. Patients are surviving and thriving into teen and adult years. The evolution of care since the late 1960’s for patients and families include routine and unexpected clinic visits, hospitalizations, and procedures. Transitions into acute care systems and subsequent return to chronic care systems are part of the process. This care is required in addition to normal routine health surveillance and illnesses impacting patients, families, resources, and support systems. Recognition of the healthy sibling impact and relationship with chronic health disease is present in the literature with inconsistent results across many diseases. The quality of life literature in CHD is progressing through the years, particularly for patients; however, lifetime healthy sibling impact of CHD continues to be void in the literature. Sibling relationships span the longest time period in a lifetime, typically longer than parents and spouses [2]. Focus on sibling impact of chronic illness is essential to understanding the family dynamics, sibling relationships, roles, and family coping mechanisms when faced with a life-threatening illness like CHD.Method: A Midwestern nuclear intact family is the focus in this case study. In 1968, an infant, second in birth order of 4 siblings, was postnatally diagnosed with complex univentricular CHD requiring repeat surgical and medical follow up throughout his lifetime. This single family review retrospectively spans over four and a half decades from the perspective of third in birth order sibling. Utilizing interviews and personal accounts, a developmental perspective of the impact growing up with an ill sibling throughout childhood and adulthood is reported.

Results: Normal developmental milestones of adulthood were achieved by all four siblings including: graduating high school, moving out of the home, marrying, childrearing, and pursuing productive careers. Divorce was not present in the nuclear family and respective adult families. Three of the four siblings graduated with a college degree and a first for our generation.

Conclusion: CHD and the acute life threatening issues associated with surgical and medical follow up impacts the family system. Compassion and empathy evolved throughout the lifespan for one sibling. Exposure to emotional, mental, and physical stressors while providing quality health care can be significant. The development of professional compassion fatigue [3] and nursing burnout in the third in birth order sibling was identified.

Family resilience was critical to positively moving forward. Eight positive resilience factors were identified as key to maintain a positive focus and live life to the fullest capacity. These included: consistent positive family support, spiritual support, family financial stability, quality health care, strong work ethic, presence of humor, focus on quality of life and normalcy, and drive for adventure and new experiences.

Keywords

Siblings; Congenital heart disease; Acute and chronic health care; Nursing profession; Compassion fatigueIntroduction

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common birth defect occurring 1 in 100 births or 1.2 million babies worldwide annually. Severe CHD occurs in 1 in 300 births or approximately 340,000 worldwide [4]. The management of CHD has rapidly progressed since introduction of pediatric cardiopulmonary bypass and advances in the medical, surgical, and nursing care has enabled “blue babies” to not only survive childhood but successfully transition to adulthood [5]. Consequently, meeting the needs of complex CHD and their families requires exploring best practices, practical resource utilization, and continual care throughout a lifetime [6].Family impact in the literature can be traced back to a study of 100 randomly selected children on infant wards. This study explored the impact of CHD on the family and at risk families, particularly “overreacting” and “generally immature” parents [7]. Empathy is assessed on healthy young siblings associated with CHD in one small sample study of 28 siblings [8]. With severe CHD, like my brother’s, a relationship to anxiety and depression is suggested in the literature [9]. In recent years, the quality of life literature demonstrates a lower health related quality of life of children and adolescents with biventricular and single ventricular CHD [10].

Qualitative research by Rempel and Harrison in 2007 identifies the need for parents to safeguard the precarious survival of the child and safeguard the precarious survival of self (and the couple) when faced with a complex single ventricle disease called hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) [11]. Rempel also identifies grandparents stepping up and helping with care of daily routines, play, and recreation. The double concern for their children and ill grandchildren, and added sibling care roles creates a triple concern for grandparents [12].

Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents are among the most common and functionally impairing mental health disorders to occur in childhood and adolescence with an increased risk for future anxiety sparking the need for identification by primary care providers [13]. The study by Stewart in 1991 describes the need of siblings to be able to talk with doctors (and other health professionals) about the illness of their sibling [14]. Inconsistent results are present in the literature regarding the well sibling and impact of chronic health disease with medical diagnosis predominantly outside of CHD and in small convenient sample sizes [15-17].

Fleary in 2013 identifies the need for further sibling research growing up with chronic health issues and highlights the emphasis a heavy focus in the oncology population. A targeted study using college students looked at questions such as: “Looking back, what would you want to happen differently about the experience?” What were your biggest fears then?” “How has the disease affected your life?” “How about now, do you have any fears or worries that stem from your sibling’s illness?” [18]. Jewsbury Conger, described the milestones of leaving home, completing education, employment, marriage, childbearing, and moving out and moving on with new roles and new relationships as milestones of adulthood [19].

In 2015, Humphrey focused on psychosocial well beings of siblings of children with life-threatening illness with the diagnosis ranging from neuromuscular (30%), genetic/congenital (27%), cardiovascular (17%), metabolic (10%), oncological (10%), and respiratory (7%). No lower psychological well-being than the general population was the outcome found and supported their prediction of presence of a positive family environment would be associated with higher levels of psychological health. This sample size was small including 24 parents and 30 siblings and also consisted of mostly Caucasian, two-parent households, and only minor financial concerns [20]. Building resilience in young children and teens throughout growth and development is essential. Ginsburg and Jablow in their book published in 2015 identified chronic disease may bring limitations and impact a child’s capabilities but does not prevent children from becoming resilient [21].

Introduction to the Case Study

CHD met our nuclear family in a small Midwest town in 1968 while the family was still growing. My parents, grandparents, family, and friends had no awareness of what CHD was or the impact. By the time I was born in 1970, the second born sibling was already showing the health care providers that he was a survivor of complex univentricular disease. It occurs in less than 1% of CHD with a high mortality up to 50% in infancy [22]. He wasn’t expected to make it to his second birthday, just one month away. He did live, grow, and moved on to a surgical procedure in order to provide more pulmonary blood flow to facilitate further growth and development.Complex univentricular CHD was such a foreign topic to the family. The anatomy and surgical interventions are listed below in Table 1. Grasping the enormity of the issues is challenging and can be very overwhelming without proper health provider guidance. In the 1960’s, the technology was not present to reliably and responsibly predict any outcomes. “The future is unknown” and “we are embarking on uncharted territory” were common conversations within our household and medical offices.Any one of these diagnosis labeled in Table 1 can be difficult to process in isolation and impact on health. Imagine to yourself how you describe this diagnosis to any lay person, parent, sibling, or family member. How do you pronounce these large medical terms much less define them? What does it mean clinically? In our family, it became known that there was a “very rare single ventricle disease” present that required unusual reorganization of my brother’s cardiac “plumbing” to keep blood flowing well to the body and all essential organs to sustain life.

Despite the complex diagnosis, CHD in my family was a fairly invisible disease of childhood to those outside looking into our family. Other than the surgical incisions in 1970 and 1985 and some activity intolerance, my brother looked and acted like any other child his age.

Extended family and parents

In this working middle class family’s experience with CHD, many supportive family members were present on the journey. Parents, now 70 and 69 years of age, were born and raised with large Catholic families consisting of 11 siblings and 6 siblings, respectively. Birth order was paternal (third youngest) and maternal (third eldest). Maternal and paternal grandparents modeled families where the father was the main breadwinner. Common to the times, most maternal and paternal siblings resided within a few mile radius of the small Midwestern town. Homebuilding and paper mill work were common careers in both families. Persistence and perseverance no matter what the task at hand were family strengths of parents and grandparents. Paternal family history of depression requiring treatment was present.

My parents married and started a family shortly after graduation. As the main breadwinner, my father worked as a master electrician in the paper mills on swing shift which meant rotating all three shifts to provide for the family. He also started his own electrical contracting business. Paternal depression, anxiety, over-eating, and alcoholism were present. Functioning as homemaker and main caregiver, my mother also supported the growing family electrical contracting business run out of the home. All four children were expected to join the workforce in the family business throughout childhood at an age appropriate developmental level to learn a strong work ethic. The opportunity for a well-paying summer employment was available at my father’s paper mill for all college students as part of work benefits.

Food, clothing, and shelter were secured by practical means with inexpensive purchases and extensive use of hand me down clothing. Lack of extra funds for playtime activities didn’t limit parental thriftiness and exposure to amazing new experiences in life. One example of this is a family purchase. Every child contributed $200 to purchase an old tri-hull roundabout boat and motor for water sports. Many times, we had three of us in tow behind the boat, including my mother who was instrumental in helping so many people learn to ski. Together the family restored, painted, and maintained the boat.

Aunts, uncles, and older cousins were babysitters for the family to provide my parents adult only time or support the activity needs of the household. My mother’s best friend from high school lived in the neighboring town. She was a professional beautician, unmarried, without children, and a great support resource close to our family. On occasions when my parents were out of town for a night or extended overnights, such as in 1985 for the Fontan operation, she provided.

Case study

In 1968, cell phones, internet, and technology gadgets to stay connected were not invented. My mother gave birth to a term son, second in birth order, at the age of twenty-three. My parents and eldest brother, then 1-year-old, were living in a duplex making plans to build a new home. My uncle and godparents lived right next door to us and were also beginning their young family. After postnatal diagnosis of a significant cardiac health concern, my brother was promptly transferred via ambulance accompanied by my father to the local children’s hospital in the state. The local hospital was two hours travel time by car with a growing pediatric cardiovascular program.

The ambulance ride was the beginning of many family trips to Milwaukee. At that time, there was no emergency room or intensive care unit. The chief of pediatric cardiology took on my brother’s case to evaluate the nature of his cardiac disease and began a longstanding and trusting relationship. Multiple family members assisted with travel to and from the hospital during this hospital stay. Upon discharge, my parents bought a baby scale and mother weighed him and diligently tracked intake, output, and weights in a green notebook. My mother would bring this evidence in to share with the cardiologist at follow up visits (Figures 1 and 2).

In 1970 a practicing general surgeon also certified in thoracic surgery, performed a Blalock-Taussig Shunt for my brother and was discharged 3 weeks later with a healing full thoracotomy. Limited open sleeping space available in the hospital hallways was utilized by my parents. They took turns traveling back and forth supporting the family back home and recovering second born son’s needs.

A dedicated pediatric cardiovascular surgery team for CHD was in place in Milwaukee and growing with a formal pediatric surgical CHD program starting in 1973 when Dr. Bert Litwin joined the practice. Diligent follow-up continued with the chief of cardiology and so did focus on normal life events. In 1973, my parents welcomed the last of their four children into the world and were settling into their newly built dream home. It was designed and built with their hands just one town line away.

Description of childhood

Breastfeeding was attempted in the first two children but ceased due to ankyloglossia, (tongue tie) and CHD respectively. All recommendations for immunizations were followed. An outbreak of chicken pox was shared as young children. No significant chronic health issues outside of environmental allergies were present impacting routine growth and developmental issues of childhood. Unexpected visits to the doctor and emergency rooms for ear infections, other childhood illnesses, stitches, and broken bones were encountered.

Three elementary schools filtered into one middle school and one high school. Living with CHD was unknown to most. Conversations and education with the school nurse about CHD did not occur on any regular basis or at all. In fact, my mother couldn’t recall who the school nurse was growing up. The school nurse had a long time dedication in the school system according to a local pharmacist who worked with her on numerous occasions advocating for the health and wellbeing of disadvantage children in the school system. She is described as, “having a personality looking through eye glasses…champion of causes to normalize children in relationship to peers with a calm, collective, reassuring, and humorous nature ”Vandenberg, L. (2014, November 20). Personal Interview.

A physical education teacher within the high school lived next door to our family. As a teacher and parent, he had an opportunity to observe my brother in gym class and being a child playing around the neighborhood. No pulse oximeters were accessible at home or school. There were times he was visibly quite blue or cyanotic with exertion. On one occasion at school, my older brother stepped up to defend my brother who was being bullied because of his cyanosis. Through the years, my brother was charged with learning and being aware of his capabilities and fatigue during any gym class and any activities that were physical exertion was in question. Study hall was always an option if needed.

Sidewalks were prevalent in our small Midwestern town and typical free play activities of childhood were encouraged outside until dark, weather permitting. Bike riding, walking, daily trips to the local swimming pool for lessons and open swim, and local pick-up games in the neighboring vacant grass lot were common events. Weekly piano lessons were encouraged for all children in the family. My mother even took a few lessons. Building forts, creating homemade go carts, playing kick the can, and performing neighborhood plays were fond memories of childhood. Indoor activities were board games and an Atari game system. As a congregation corner house in the neighborhood, friends and cousins were encouraged to play, hang out, and have sleepovers. Humor, laughter, and full out belly laughs were common, particularly when used with competition between sibling activities. Learning to water ski, kneeboard, parasail, and taking part in the activities on our simple round about boat were family fun times of learning. My parents were new to boating, learned with us, and entrusted us to engage in opportunities to take the boat out as teens once we accomplished driving and boat safety.

Helicopter parenting or overprotecting mothers and fathers with excessive interest in their children’s activities was simply not an option in our family because my parents could not be present for all open and unstructured free time. Working two jobs, my father had little time left in the day. Play dates were not organized for us by our mother. We played with whoever was around making sure we respected my father’s time to sleep based on his swing shift schedule. Family members and cousins were plentiful for playmates and support. Running a household, providing a safe environment, performing personal business chores and accounting, volunteering as a den mother for cub scouts, and organizing memorable and simple birthday celebration parties kept my mother very busy.

Day trip family outings throughout the state and neighboring states included local parks, zoos, theme parks, and lakes. Annually at a minimum, a traditional day long trip to Great America was an essential destination. We would arrive at 10 am and leave at 10 pm to get the most value out of our day long ticket running from coaster to coaster. As kids, we often promptly fell asleep as soon as we got in the car for the 3 hour drive home. Follow up visits in Milwaukee were often tied into family outings. Over time, these outings were based on health status. If all was going well, they were spread out to annually. Annual vacations up north at various rental cottages were rituals often shared with uncles, aunts, and cousins close in age to our family. Options to bring a friend along were often part of the planning as we grew older.

Expectations of family life

Family expectations to provide quality medical support, insurance, and quality of life for all four siblings remained the utmost focus. My father navigated this consistently by working in a paper mill on swing shift, signing up for overtime and extra shifts, running his electrical contracting business, and maintaining health benefits with the local paper company.

Expectations within the household for routine chores, education, and music experience were consistent among all four siblings. No allowances were provided. Anything above and beyond routine safety, food, shelter, and clothing was provided by our own funds. Educational tutors were provided during prolonged hospitalizations to keep up with current class work. In our early and late teen years, independence and responsibility grew. In addition to learning driver’s safety, expectations to obtain boater and motorcycle safety courses at the local technical college were added.

Holiday gift giving by parents was consistent to the dollar amount for each child. My mother made certain not to demonstrate any favoritism. Typical sibling rivalry was present, particularly between the second and third born. Powerful themes of continued education and learning throughout a lifetime, proper prior planning, fostering independence, and striving for the best with whatever you do or encounter in life were expected and discussed throughout childhood. The locus of control modeled in the family was internally focused with empathy and compassion modeled.

Perspective growing up from a sister and future nurse

One “aha” or “lightbulb” moment in my anatomy and physiology class occurred in 9th grade when we discussed the heart and all its components. While providing some clarity, it was still difficult to understand his diagnosis and how it related to what I saw clinically in my brother. CHD was fairly invisible to my eyes as a child just like others who looked into our family. His first surgery occurred when I was three months old; thus, no memory of the event. To me, he kept up with all of us as siblings and sported a large healed thoracotomy incision as a battle wound of early childhood. While thinner, bluer lips, and different shape to his nail beds, he demonstrated flexibly with muscle and ligaments and skills in math and puzzle solving. Competitive sports were discouraged by the health team; however, he didn’t shy from activity and learned how to waterski, kneeboard, parasail, and navigate the sailboat and sailboard with ease. He could ride the unicycle all over town. In my eyes, he never appeared to be a sick child until he broke his arm with an open fracture at the elementary playground falling from a dome landing in traction at the local hospital for many weeks (Figures 3 and 4).

While in high school, the decision was made by the medical team and my parents that it was time to have a Fontan procedure to help with his cyanosis and restricted blood flow. This surgery wasn’t even an option when my brother was born but was now a reasonable treatment option. When it came time for his surgery in 1985, he was referred to a world renowned center of excellence with more experience in the Fontan procedure.

The decision for surgery moved CHD in the foreground again from his place of normalcy. My parents navigated the insurance coverage, lodging, and preparations to support our entire family system. This time period is when the unknown and mystery of CHD really sparked my interest. I had no idea what to expect when my brother went off to the hospital and honestly wanted my parent’s attention too. The local community hospital was only 10 miles away from home. A visit, play, sharing treats, and go returning home in the same day were easy. The hospital this time was 250 miles away and difficult task.

Aware that my parents were stressed, I continued to wear my “good child” hat to do what was needed when extra chores were asked of me. Circling in my mind were countless questions and no real answers. What would it be like? What would be done? Would he die? Would he be in pain? Can I visit? Can I call? Why does he get all the attention? What are the expectations and length of hospital stay? How would this impact our family? How would the rest of us keep going?

My parents had a lot of these questions too and trusted their child’s pediatric cardiologist to continue guiding and reassuring just as he did in 1968, 1970, and at every follow-up visit. Providing a more balanced circulation was the target for a better quality of life. Research and surgical techniques progressed in the decades up to 1985, but there was still many unknowns and uncertainties for patients and family’s journey with CHD into adulthood. The Fontan procedure was a major operation with risks of significant potential complications, including death.

The first few weeks, he was very ill and puffy but had “pink” lips and nail beds per my parents report. I never visited while he was hospitalized and never had the courage to ask for an opportunity trying not to disrupt the flow in the family. After four weeks, discharge home with a healing full sternotomy and multiple chest tube sites as his “bragging rights” and evidence of his hospital course (Figure 5). As I grew older into adulthood, the postoperative significance of persistent chest tube drainage became clearer and remains a very real complication issue extending length of hospitalizations. Persistent chest tube drainage and hospitalization in the “chest tube hotel,” as my family describes it, was the only significant complication. Similar to the hospitalization as a young teen for the fracture, tutors and educational support continued throughout the recovery process to maintain education as a primary focus of growth and development.

In retrospect, many fears and mystery surrounding my brother’s hospitalization were present. I had no concept of what a chest tube was or what it meant to be hospitalized after open heart surgery. My parents spoke of “drainage tubes” but what was that? As a visual learner, I suspect my fears and anxieties could have been reassured with a thoughtful health care provider and physical presence at the bedside. Today, there are many more educational resources and providers such as: nursing educators, practitioners, child life specialists, and social workers trained to facilitate families through the process of a hospitalization.

As I grew older, I required more in depth answers to my questions and was still puzzled with my still very primitive understanding of a complex disease process and anatomy. The cardiologists and experts like my brother became my guide to understanding. My brother often down played things and took the approach like “It’s no big deal” when it came time to describing CHD and approach to impact on him which is very similar to findings in the literature by Shearer in 2013 [23]. My brother was always open to sharing information, promoting research in CHD, and talked about how he felt like a “guinea pig” as one of the oldest single ventricle survivors. At times, there were many residents and fellows standing in line to meet, listen, and examine him. As questions were answered, I learned more and came up with even more questions.

I recall clearly a moment in 1993 practicing as a new graduate nurse on the oncology and transplant floor. While working a shift at the hospital, my brother was having a cardiac catheterization on a different floor. Taking a break from patient care, I stopped by to see him before the procedure to be with him. His long time primary cardiologist had retired and case had been transitioned to a new chief of pediatric cardiology.

Separated by college life for a few years, I saw my brother sitting on the gurney with hospital gown on and bare feet with more clinical eyes. I saw brown spots or evidence of venous stasis bilaterally up to his mid shin. As a nurse became very concerned and made sure the cardiologist was also aware of my concern. Learning about congestive heart failure (CHF) in school and caring for adult patients in my nursing practicums with CHF raised many red flags in my eyes. This period of time was the first moment I realized that my brother’s heart was not functioning as well as everyone would like and the uncertainty of his future was unknown. Tears were shed on the way home from work that day.

The risk associated with CHD increased with age and continued to be present throughout adult life including: arrhythmias, ventricular function, and thrombus that required medical and surgical interventions. Another acute event would surface, and the face of CHD would again take priority in forcing an action management plan to return to a baseline chronic health management state (Figure 6). These unpredictable and predictable transitions are an often natural occurrence in CHD and impact every family member (patient, parent, sibling, grandparent, and beyond).

The natural milestones of my young adult life include: daughter, sibling, wife, mother, aunt, godmother, and nurse practitioner. As time went by, there were many milestones of adulthood shared with my brother and family. As his health failed, the anxiety, fear, and worry about his quality of life and survival grew. Having solid mentors and health care leaders within CHD to talk through these risks and benefits openly and honestly at every step of the way helped immensely to solidify the reality of the situation for me as a sibling and nurse.

Looking back, his last year of life waiting for transplant was the most difficult to deal with as a nurse. Knowing the exact moment by moment congestive heart failure plan of care and last echocardiogram finding would not change the outcome. What would that get me other than more anxiety and fear of the unknown? While my brother has always been very transparent about his care plan with his sister, this was not the time. Being cared for by a center of excellence was reassuring and aided in the process of letting go of my inherent evidence based practice thinking. The priceless moments as a sister were more important to preserve. From my perspective, he was still attached to an intravenous line unable to return home.

As hard as it was to let go of the medical, I did. Focusing on being the best sister I could was primary. Regular visits were scheduled and overnights at the local hotel. They were not vacations by any normal definition of family holidays, but we made them fun connections, laughing whenever we could. Adventures within the walls of the hospital grounds were many: playing some “sour” notes of his favorite Billy Joel songs on the piano, attending a local conference, bringing in a fresh snowball, strolling to the meditation room or chapel, sporting a classic Wisconsin Packer’s fan cheesehead throughout the hospital, doing yoga in his room, and creating a root beer taste test challenge for family, patients, and staff.

Optimism was high when the call came of a viable donor for transplant. Interestingly, he was transplanted on national sibling day of 2015.The stars seemed to all align but with that, stress among the family also heightened. My mother was the last one to say good-bye to him before going to the operating room pre transplant. She was looking at him as if it was her baby some 45 years earlier going to his first surgery. He knew my mom and ability to get lost and told her that “God has His plan,” she needed to stop, and say good-bye for now.

With this, instinctively, my nursing brain went back into action and I didn’t suppress it because the risks were so high and I needed answers to process this next phase and keep the family calm and updated. How would his body tolerate the new organ? Would he have to return to the operating room and how often? Would he be comfortable and when would he wake up to see me again? Would complications of bleeding, acidosis, and arrhythmias be manageable? What untoward complications might arise? Would he survive this moment, hour, day, or week? Would he make it out of the hospital alive? How were my parents going to cope? How was I going to keep the family updated practically and in simple terms to positively cope with such a difficult health issue?

Outcomes

Eight themes or key factors of resilience emerged throughout interviews• Family support

• Spiritual support

• Family financial stability

• Quality health care

• Strong work ethic

• Humor

• Focus on quality of life and normalcy

• Drive for adventure, pushing boundaries, and new lifeexperiences

Adult sibling summary

First born (1966): The first born married out of high school and started a family with two beautiful young daughters and is a grandfather of three children. Carrying on my father’s trade as a master electrician, he is employed in a local paper mill. He recently lost his long time wife to Acute Myeloid Leukemia secondary to breast cancer treatment in 2015 at the age of forty-eight. The grief and loss for my eldest brother this past year has been incredibly significant with the loss of his brother and wife within a 4 month time period.

Second born (1968): Second born was CHD married shortly after college graduation and has four lovely children. Choosing a college degree in chemistry, his career began with some travel. As a “mathlete,” he enjoyed tutoring students. He transitioned to opening a small photography business. He continued employment up until his hospital admission pre transplant for a local non-profit providing rehabilitation and employment services for people with disabilities and special needs. Unfortunately, my brother lost his battle with CHD in May of 2015.

His life was lost, but he taught and left behind so many salient lessons. For my brother, life was not defined by CHD, the #1 birth defect. Sometimes supports and resources were needed in his lifetime, but as he would say, “everyone has an issue in life to deal with and mine is CHD”. His life was fulfilling, rewarding, and had a persistent thirst for learning. His humor was a touching point to so many who knew him and brought levity to many serious moments in life. He valued his gift of life and believed it was valuable, fragile, and should never be taken for granted. My brother, a very spiritual young man with incredible faith and hope, often said, “God has His plan”. My brother trusted in the CHD research of the past, present, and future to carry him through life to the best of ability.

The photo (Figure 7) below is a photo of one of our last moments together at my house before he went into the hospital for a long term stay. At the time this photo was taken, we were celebrating my first born graduating high school and moving onto college in the fall semester. If you look close enough, you will see the logo of the local chapter of Mended Little Hearts support group for CHD on the left chest. His left arm has an emblem created by my brother and familyin 2011.

Quote from my brother on activity intolerance (November 20, 2014):

“I think one of the best things Mom and Dad did was treat me as normal as any of you guys (3 siblings)….I knew I tired more quickly, but that didn’t stop me from participating….I see some people now that will almost isolate their special needs child and protect them from anything and everything….that child has no hope of living a normal life”.

Fourth born (1973): The fourth born chose a career in electrical engineering, is married, and employed in Illinois. His job is a senior level job requiring world travel commitments. For an extended period of time he relocated to Denmark. While there, my mother spent time visiting and enjoying her first ever European holiday.

Third born (1970): A nursing career was envisioned in high school for the third born. After discussions with mentors, and parents, I gained experience employed as a certified nursing assistant and activity director at local Alzheimer’s Care unit in high school and early college years. Utilizing the summer benefit at my father’s place of employment, I was able to pay my way through college like my two other brothers. After pursuing a Bachelor of Science degree in nursing at the local state university, I married in 1992 and moved to the Milwaukee area. In 1996 and 2002, mother of two healthy children was added to my adult milestones.

A pediatric career began at the local children’s hospital in the pediatric oncology and transplant unit. Transferring to the pediatric intensive care unit, my drive to pursue an advanced degree in nursing was initiated. Following graduation in 1999, I began my pediatric nurse practitioner (PNP) career in a full-time role in pediatric cardiology. Teamwork, advancing clinical skills, autonomy, and professional development were modeled by mentors in this new and developing role. Educational tools for parents, nutritional support [24], protocol development, and research were career achievements. The home surveillance monitoring program (HMP)was developed for high risk interstage time period for CHD between stage 1 and stage 2 palliation utilizing a home scale, pulse oximeter, binder, and close interstage clinical management [25]. In addition, the Fontan protocol for postoperative persistent chest tube drainage was developed [26].

In 2007, my spouse’s job relocated our family to New England. There my career took on further development at the world renowned Figure 7: Adult milestone June 2014. pediatric cardiovascular surgery center from 2008-2013. During this time, a full-time position was not the best work life balance for our family. A part-time PNP position in a high volume surgical and referral center was undertaken. In addition to my role on the ward, I collaborated on parent educational tools, facilitated transferring the Wisconsin born HMP into a large institution [27,28], presented at the American Heart Association annual conference [29], and participated with the local team for the National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative [30,31]. Family, work, life balance was disrupted near the end of my career in New England. Anxiety, depression, nursing burnout, and professional compassion fatigue arose in 2012.This was treated with the help of a primary internal medical specialist, mental health support, and Bikram yoga.

In 2013, our family relocated back to the Midwest due to my husband’s job advancement. Primary focus during this transition time was on my nuclear family (husband, daughter, and son), extended family, self-care, and volunteering. My daughter was finishing her final year at a new high school and son entering middle school. One year later in the fall of 2014, my brother was chronically hospitalized awaiting heart transplant. Regular visits to support quality of life were important to continue our sibling relationship. My daughter continued her relationship with her uncle by attending many of these visits. My daughter is now a sophomore in college with an interest in the life science space. My son is finishing up eighth grade and active in extracurricular sports and music activities. Both are thriving. Unfortunately, my brother’s outcome was not as our family had dreamed and never left the hospital alive secondary to co-morbid issues. He died a few weeks following his 47th birthday and will now be forever in my heart. I am truly grateful for the 45 years I had with him as a sister. Learning about and dealing with sibling grief was the next personal challenge to navigate.

As part of my CHD healing journey, I recently attended the advocacy conference with my 70 year old mother in Washington, DC. Collaborating with leaders in the field of CHD, we told our family’s story and advocated in February of 2016 with our local congressman for increased awareness of CHD, support for quality treatment options, and research for the number one birth defect [32,33]. The Centers for Disease Control and National Institutes of Health also support the cause. This effort cannot be done in isolation. Please read about the re-authorization act put forward in November of 2015, reach out to your congressman, and keep CHD present and visible.

Reflecting on my experiences with CHD over a lifetime, my brother, family, and countless other CHD families that have touched my life have reinforced and taught me valuable insights about the importance of striving for normalcy. There are more supports and resources often required [34], but life is not defined by the disease. Life with CHD can be complicated, frustrating, and unfair. It also can be fulfilling, rewarding, and demonstrate to others the value of making the most of the precious gift we are all given.

Discussion

This case study provides one example of a healthy sibling’s perspective on the family growing up with CHD. Hope, positive outlook, surgical advancement, and medical support within the health care profession were present through nearly five decades of life in addition to typical normal developmental milestones. Never was my brother lost to medical follow up in his lifetime. Learning about the impact of CHD on my brother and our family system was not a choice. Burdens in care (financial and otherwise) were present throughout the lifespan. Essential components of resilience in our family included extended family support, spiritual support, family financial stability, quality health care, strong work ethic, humor, focus on quality of life and normalcy, and drive for adventure including pushing boundaries toward new life experiences. Ultimately adult milestones and successful contributions to the community at large were achieved for all four siblings.Supporting sibling’s understanding of CHD throughout the developmental spectrum is important to demystify the disease, treatment, and grief process. In my lifetime alone, more focus is being given to this need through child life specialists. The entrance of the hospital where my brother was treated for a large part of his lifetime now contains a sibling care room [35]. Within the last two years alone, discussions with health professional colleagues and expert parents in CHD have been increasingly positive that sibling presence is not being forgotten as part of the overall assessment of the care plan. I am hopeful that this will continue.

This case highlights the reality of psychological stressors presenting throughout a lifetime for the third in birth order sibling and PNP experienced in CHD. One could speculate that regardless of the presence of CHD, I may have still developed psychological stressors in 2012.Any nurse or health care provider exposed to the fragility of life in a work environment is at risk. A compassionate and empathetic heart, my brother’s fragility in infancy, and nursing experience with consistent life and death exposure in the interstage period likely played a role in the development of compassion fatigue and burnout. Without proper treatment at that time, I may have encountered additional challenges dealing with the significant health crisis and ultimate death of my brother a few years later. I am forever grateful for the resources present within my family and health care team to address, treat, and manage the issue and move towards a healthier today and tomorrow.

Conclusion

Changing population of CHDCHD care has evolved greatly in the last several decades yet remains common, costly, serious, and bears no cure. Medical advances and better outcomes have continued to show promise. Children today that are diagnosed with single ventricle disease undergo the Fontan operation at much earlier time point than my brother, typically 2-4 years of age. Fetal intervention is a possibility for some lesions [36]. With fetal diagnosis, parents and their families are impacted by the transition of a new member into the family and the complexities of a critical health issue that must be addressed early in life [37]. In essence, they are trying to navigate the “emotional tightrope” of caregiving and parental transitions [38]. By clustering the medical and surgical treatments earlier in time, there is increased frequency of disruption within the family system, burden of health and technology costs, stress, and depletion of family resources.

Stress in terms of finances, emotional drain, and family member burden are reported in the literature [39-41]. Based on practical experience over greater than 20 years of nursing experience, the CHD families of today comprise a mixture of dual income households with more financial health care coverage concerns and often less extended family in close proximity. This can impact a family’s ability to positively engage in care and cope positively to these variables, particularly those with limited resources at baseline (i.e. single parent, lack of extended family support, lower socioeconomic, poverty, non- English speaking or language barrier, or another sibling with chronic health needs).

Promoting healthy families for the future

Realistic hope and faith for a positive medical outcome must be preserved in addition to preparation for an unforeseen fatal outcome. When a patient is lost due to CHD and/or co-morbidity factors, the significant death is palpable for the entire family, particularly when nearly five decades of life experiences are shared. Moving through the grief and loss is a challenging and ongoing process for all. As an adult sibling experiencing a loss of my brother, the commonly termed “forgotten griever” persisted throughout my grief, loss, and mourning. Current research is slowly growing in the area of adult sibling bereavement [42]. Focusing on a new way to live in the present moment without forgetting those left behind is critical to maintaining overall health of all family impacted by CHD, (whether sibling, mother, father, wife, son, daughter, aunt, uncle, or other significant relationship). Bereavement programs need to be reevaluated as part of the future to provide developmental supports for all ages impacted by CHD, particularly with a growing population of adult congenital heart disease patients.

This case study represents one opportunity to understand the complexities of a sibling relationship (and family) and developmental milestones throughout four decades as it relates to CHD. While retrospective and not generalizable, it offers a nursing and sibling point of view into one nuclear family’s experience navigating a complex CHD diagnosis throughout a lifetime. Countless other untold personal sibling journeys need to be told and heard in this growing population of families impacted by CHD. Providing qualitative and prospective research studies with larger sample sizes (including patients, parents, siblings, and grandparents) and longer assessment time spans is essential for future research. With this fundamental next step, issues can be identified in a timely fashion, assessed, and treated with the focus on the goal of a healthier future for all those impacted by CHD.

Maintaining healthy lifestyle goals including mind, body, and spirit is critical in lieu of the additional life-threatening stresses CHD families encounter. Fostering and modeling resiliency in families with a dynamic and ever changing treatment plans is important. Whenever possible, care plans need to engage and be mindful of these healthy lifestyle goals, de-intensify fears, provide practical action plans, encourage resources for support, and focus on normalcy. Nonjudgmental assessment and intervention of current issues must occur by all team members (family, primary care provider, nursing, cardiologist, surgeon, subspecialty, etc.) regardless of the issue. Psychosocial issues such as anxiety, depression, compassion fatigue, and caregiver burnout are not a sign of weakness. Increased education, support, and awareness for patients, families, and providers are necessary to providing prompt assessment and intervention.

Striving for normal developmental milestones throughout a lifetime such as a second birthday, starting kindergarten, graduating high school, graduating college, marrying, pursing an active career, and starting a family must continue to be celebrated and cherished. With the complexities and uncertainties involved with living life surrounded by CHD, these milestones often require more steps to achieve. The accomplishment and pride associated with the achievement is priceless.

References

- CDC (2015) Congenital Heart Defects (CHDs): Data & statistics. Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Lamb ME, Sutton-Smith B (2014) Sibling relationships: Their nature and significance across a lifespan. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New York.

- Melvin CS (2015) Historical review in understanding burnout, professional compassion fatigue, and secondary traumatic stress disorder from a hospice and palliative nursing perspective. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 17: 66-72.

- Botto LD (2015) Epidemiology and Prevention of Congenital Heart Defects. In: Muenke M, Kruszka PS, Sable CA, Belmont JW (Eds). Congenital Heart Disease: Molecular Genetics, Principles of Diagnosis and Treatment. Basel, Karger, pp. 28-45.

- Gurvitz M, Saidi A (2014) Transition in congenital heart disease: It takes a village. Heart 100: 1075-1076.

- Marelli AJ, Ionescu-Ittu R, Mackie AS, Guo L, Dendukuri N, et al. (2014) Lifetime prevalence of congenital heart disease in the general population from 2000 to 2010. Circulation 130: 749.

- Apley J, Barbour R, Westmacott I (1967) Impact of congenital heart disease on the family: Preliminary report. Brit Med J 1: 103-105.

- Janus M, Goldberg S (1995) Sibling empathy and behavioural adjustment of children with chronic illness. Child Care Health Dev 21: 321-331.

- Solberg O, Dale MT, Holmstrøm H, Eskedal LT, Landolt MA, et al. (2011) Long-term symptoms of depression and anxiety in mothers of infants with congenital heart defects. J Pediatric Psychol 36: 179-187.

- Mellion K, Uzark K, Cassedy A, Drotar D, Wernovsky G, et al. (2014) Health-related quality of life outcomes in children and adolescents with congenital heart disease. J Pediatr 164: 781-788.

- Rempel GR, Harrison MJ (2007) Safeguarding precarious survival: parenting children who have life-threatening heart disease. Qual Health Res 17: 824-837.

- Ravindran VP, Rempel GR (2010) Grandparents and siblings of children with congenital heart disease. J Adv Nurs 67: 169-175.

- Rockhill C, Kodish I, DiBattisto C, Macias M, Varley C, et al. (2010) Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Curr Probl Pediat Adolesc Health Care 40: 66-99.

- Stewart DA, Stein A, Forrest GC, Clark DM (1992) Psychosocial adjustment in siblings of children with chronic life-threatening illness: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 33: 779-784.

- Barlow JH, Ellard DR (2006) The psychosocial well-being of children with chronic disease, their parents and siblings: an overview of the research evidence base. Child Care Health Dev 32: 19-31.

- 16. Incledon E, Williams L, Hazell T, Heard TR, Flowers A, et al. (2013) A review of factors associated with mental health in siblings of children with chronic illness. J Child Health Care 21: 1-13.

- Sharpe D, Rossiter L (2002) Siblings of children with a chronic illness: A meta-analysis. J Pediatric Psychol 27: 699-710.

- Fleary SA, Heffer RW (2013) Impact of growing up with a chronically ill sibling on well siblings’ late adolescent functioning. ISRN Family Med 2013: 1-8.

- Conger KJ, Little WM (2010) Sibling relationships during the transition to adulthood. Child Dev Perspect 4: 87-94.

- Humphrey LM, Hill DL, Carroll KW, Rourke M, Kang TI, et al. (2015) Psychological well-being and family environment of siblings of children with life threatening illness. J Palliat Med 18: 981-984.

- Ginsburg KR, Jablow MM (2014) Building resilience in children and teens: Giving kids roots and wings, (3rd edn). American Academy of Pediatrics, pp. 39-50, 91-98.

- Gopal G, Suresh R, Kumar GM (2014) Univentricular heart with a common atrium-a rare complex cyanotic congenital heart disease. Int J Pharm Biomed Res 5: 42-45.

- Shearer K, Rempel GR, Norris CM, Magill-Evans J (2012) It's no big deal: adolescents with congenital heart disease. J Pediatr Nurs 28: 28-36.

- Steltzer M, Rudd, N, Pick B (2005) Nutrition care for newborns with congenital heart disease. Clin Perinatol 32: 1017-1030.

- Ghanayem NS, Hoffman GM, Mussatto KA, Cava JR, Frommelt PC, et al. (2003) Home surveillance program prevents interstage mortality after the Norwood procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 126: 1367-1377.

- Cava JR, Bevandic SM, Steltzer MM, Tweddell JS (2005) A medical strategy to reduce persistent chest tube drainage after the Fontan operation. Am J Cardiol 96: 130-133.

- Steltzer M (2011) Implementation of a home monitoring program for interstage management of infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome or other single ventricle physiology. Poster presentation for NAPNAP conference in Baltimore, MD.

- Steltzer M (2011) Interstage outcomes for infants with single ventricle physiology managed in a home monitoring program. Poster presentation for NAPNAP conference in Baltimore, MD.

- Steltzer M (2010) Discharge preparation and parent education. Invited speaker for the American Heart Association conference in Chicago, IL.

- (2016) National Pediatric Cardiology: Quality improvement collaborative.

- Steltzer M (2012) Care transitions. Invited speaker for the JCCHDQI conference in Cincinnati, OH.

- Pediatric Congenital Heart Association (2016) Conquer congenital heart disease.

- Pediatric Congenital Heart Association (2016) Conquering CHD.

- Rempel GR, Magill-Evans J, Wiart L, Mackie A, Rinaldi C, et al. (2014) Strengthening family resilience by assessing demands and resources for parents whose children have complex cross-sectoral service needs. ACCFCR Investigator-Driven Research Grant, pp. 1-3.

- Fitzgerald M (2016) Playroom of Hope sibling care room focuses on brothers and sister. Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin Blog.

- Wilkins-Haug LE, Benson CB, Tworetzky W, Marshall AC, Jennings RW, et al. (2005) In-utero intervention for hypoplastic left heart syndrome--a perinatologist’s perspective. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 26: 481-486.

- McKechnie AC, Pridham K, Tluczek A (2015) Preparing heart and mind for becoming a parent following a diagnosis of fetal anomaly. Qual Health Res 25: 1182-1198.

- McKechnie AC, Pridham K, Tluczek A (2016) Walking the “Emotional Tightrope” from pregnancy to parenthood: Understanding parental motivation to manage health care and distress after a fetal diagnosis of complex congenital heart disease. J Fam Nurs [Epub ahead of print].

- Connor JA, Kline NE, Mott S, Harris SK, Jenkins KJ (2005) 69 Economic burden of congenital heart disease on families. Pediatr Res 58: 366.

- Connor JA, Kline NE, Mott S, Harris SK, Jenkins KJ (2010) The meaning of cost for families of children with congenital heart disease. J Pediatr Health Care 24: 318-325.

- Cassedy A, Drotar D, Ittenbach R, Hottinger S, Wray J, et al. (2013) Impact of socio-economic status on health related quality of life for children and adolescents with heart disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes 11: 99.

- Wright PM (2016) Adult sibling bereavement: Influences, consequences, and interventions. Illness, Crisis Loss 24: 34-45.