Journal of Parkinsons disease and Alzheimers disease

Download PDF

Review Article

Effects of Non-PharmacologicalTreatments on Quality of Life in Parkinson’s Disease: A Review

Sangwoo Ahn 1* , Yan Chen 2 , Tim Bredow 3 , Corjena Cheung 1 and Fang Yu 1

- 1 University of Minnesota School of Nursing, Minneapolis, Minnesota

- 2 Taihe Hospital, Hubei Province, China

- 3 Department of Nursing, Bethel University, Arden Hills, MN 55112, USA

* Address for Correspondence: Sangwoo Ahn, University of Minnesota School of Nursing, 925 Delaware St SE, Minneapolis, MN 55414, Minnesota, USA, Tel: 1-651-605-1485; Fax: 1-612-625-7180; E-mail: ahnxx230@umn.edu

Citation: Ahn S, Chen Y, Bredow T, Cheung C, Yu F. Effects of Non-Pharmacological Treatments on Quality of Life in Parkinson’s Disease: A Review. JParkinsons Dis Alzheimer Dis. 2017;4(1): 10.

Journal of Parkinson’s disease &Alzheimer’s disease| ISSN: 2376-922X | Volume: 4, Issue: 1

Submission: 14 March, 2017| Accepted: 10 April, 2017 | Published: 20 April, 2017

Submission: 14 March, 2017| Accepted: 10 April, 2017 | Published: 20 April, 2017

Abstract

Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative chronic condition with a declining trajectory and lack of a cure, making quality of life an important aspect of care. The purpose of this literature review was to analyze the state-of-the-science on the effects of non-pharmacological treatments on quality of life in person’s with Parkinson’s disease. Literature search was conducted using keywords in electronic databases up to September 1, 2016 and cross-searching the references of identified articles. Of the 259 articles generated, 26 met the eligibility criteria and were included in this review. The majority of studies (77%) were Level I evidence and 23% Level II evidence. The levels of study quality were: strong (50%), moderate (15%), and weak (35%). The interventions varied across studies with 15 studies evaluating a similar intervention. About 58% of the studies showed that the interventions improved quality of life. In conclusion, a variety of non-pharmacological interventions have been increasingly studied for their effects on quality of life in Parkinson’s disease, showing initial promising results. However, most interventions were only examined by a limited number of studies and the minimal and optimal intervention doses needed for improving quality of life are yet unknown.

Keywords

Aging; Parkinson’s disease; Quality of life; Therapy

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a multifaceted, neurodegenerative chronic disease with a declining trajectory, afflicting approximately 0.4-1% of people 60 to 79 years of age and 1.9% of those 80 years old and older worldwide [ 1 ]. In the United States alone, PD affects over one million people with an approximate 60,000 new cases each year and an annual cost of $ 25 billion [ 2 , 3 ]. The symptoms of PD include motor (bradykinesia, postural instability, rigidity, and resting tremor) and non-motor (depression, anxiety, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and cognitive impairment) symptoms. While the etiologies of PD are still unknown, deficient dopamine in the substantia nigra of the brain is well-established as the cause for motor symptoms [ 4 ]. However, dopamine deficiency alone cannot explain the non-motor symptoms which can be more disabling and challenging to manage than motor symptoms [ 5 ].

Given the lack of a cure and the chronic nature of PD, improving quality of life (QOL) is paramount for persons with PD and their families. QOL is increasingly recognized as an essential outcome in PD intervention studies [ 6 ]. Medications such as levodopa/carbidopa and surgical interventions such as deep brain stimulation show strong efficacy on improving motor symptoms and QOL [ 7 , 8 ]. In contrast, the efficacy of drug treatments for non-motor symptoms is equivocal and drugs for non-motor symptoms could actually interfere with the effectiveness of levodopa/carbidopa and/or aggravate motor symptoms, leading to poor QOL [ 5 , 9 ]. On the other hand, nonpharmacological interventions, e.g., music and exercises, have been increasingly tested to improve motor and non-motor symptoms due to their low profile of adverse events [ 10 ]. However, it is unclear how these non-pharmacological interventions affect QOL in PD. Hence, the purpose of this review was to analyze the state-of-the-science on the effects of non-pharmacological interventions on QOL in persons with PD. Since the last review of QOL in persons with PD was conducted in 2012 [ 11 ], this review fills the gap with updated and new evidence.

Methods

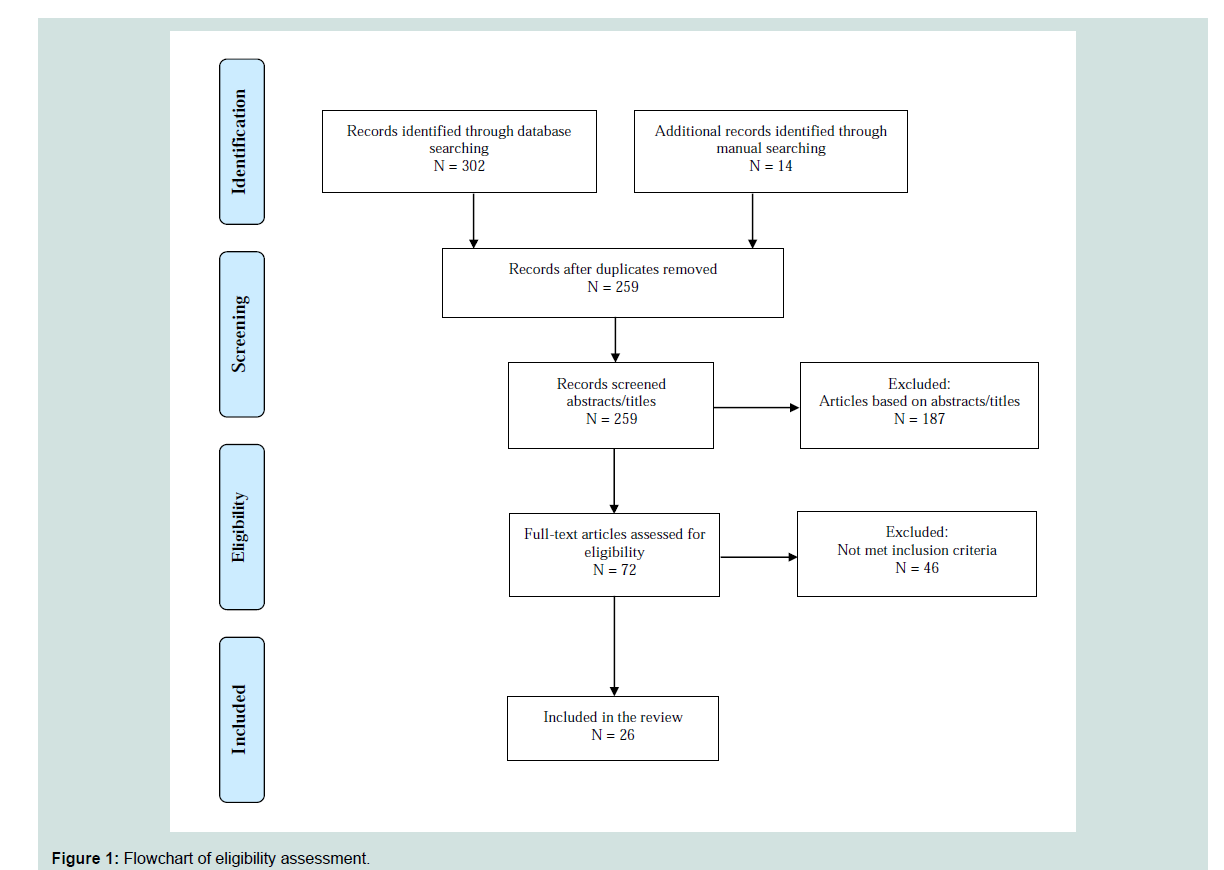

The literature search was conducted in 5 steps. First, electronic databases of PubMed, CINHAL, and PsycINFO were searched from the beginning dates of each database to September 1, 2016 by using keywords matched to medical subject headings: “Parkinson’s disease/ therapy” and “QOL”. Second, articles were excluded using keywords matched to medical subject headings: “drug therapy”, “prescription drugs” and “deep brain stimulation”. Two hundred and forty five articles were generated. Third, the study titles and abstracts were reviewed using the following inclusion criteria: 1) publication in English; 2) QOL assessed as an outcome; and 3) randomized control trial (RCT), experimental, or quasi-experimental design. Forth, studies meeting the inclusion criteria were screened out if they met at least one of the exclusion criteria: 1) surgical intervention; and 2) case study. If the abstract of a study did not provide enough information to determine its eligibility, the full article was reviewed. Lastly, we cross-searched the references of the selected studies from database search and identified 14 additional studies. Of the total 259 studies identified, 26 met the eligibility criteria and were included in this review ( Figure 1 ).

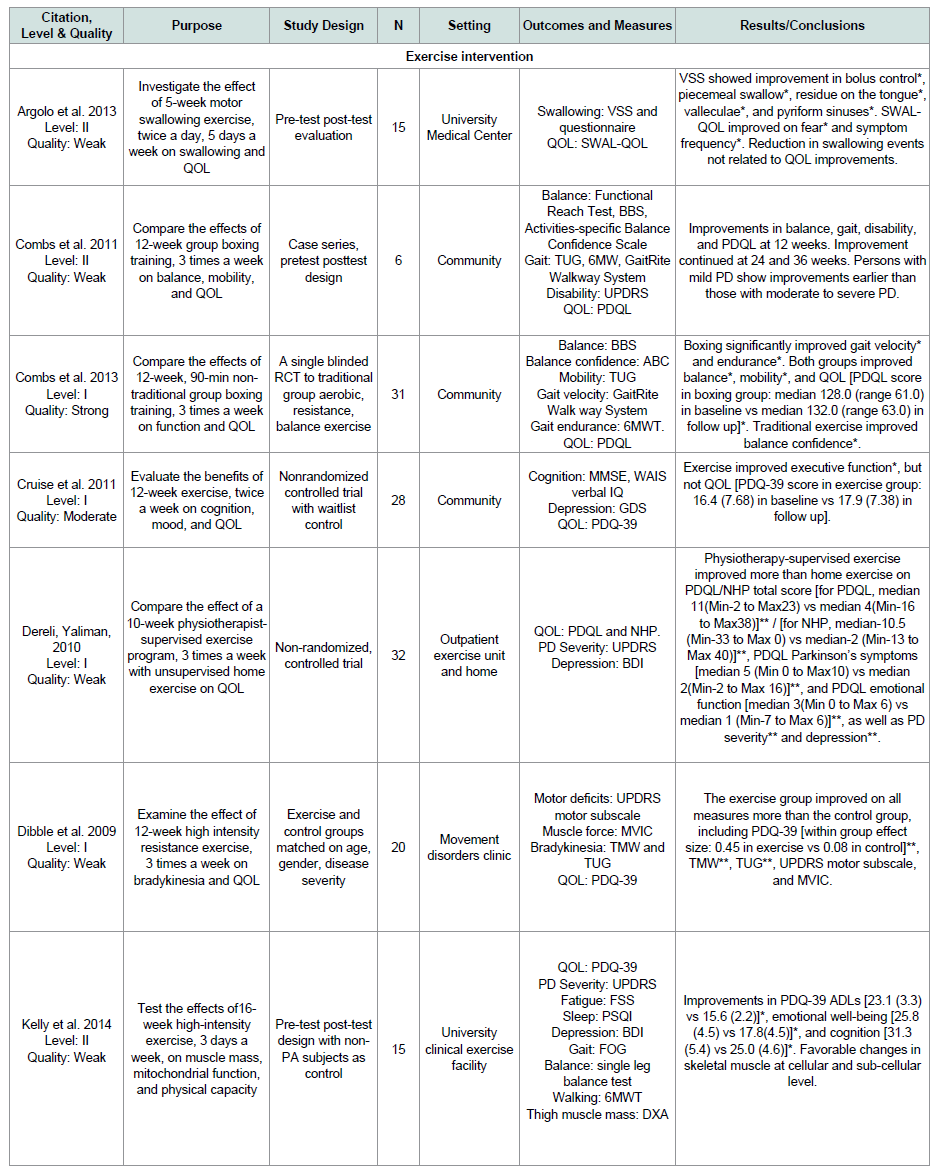

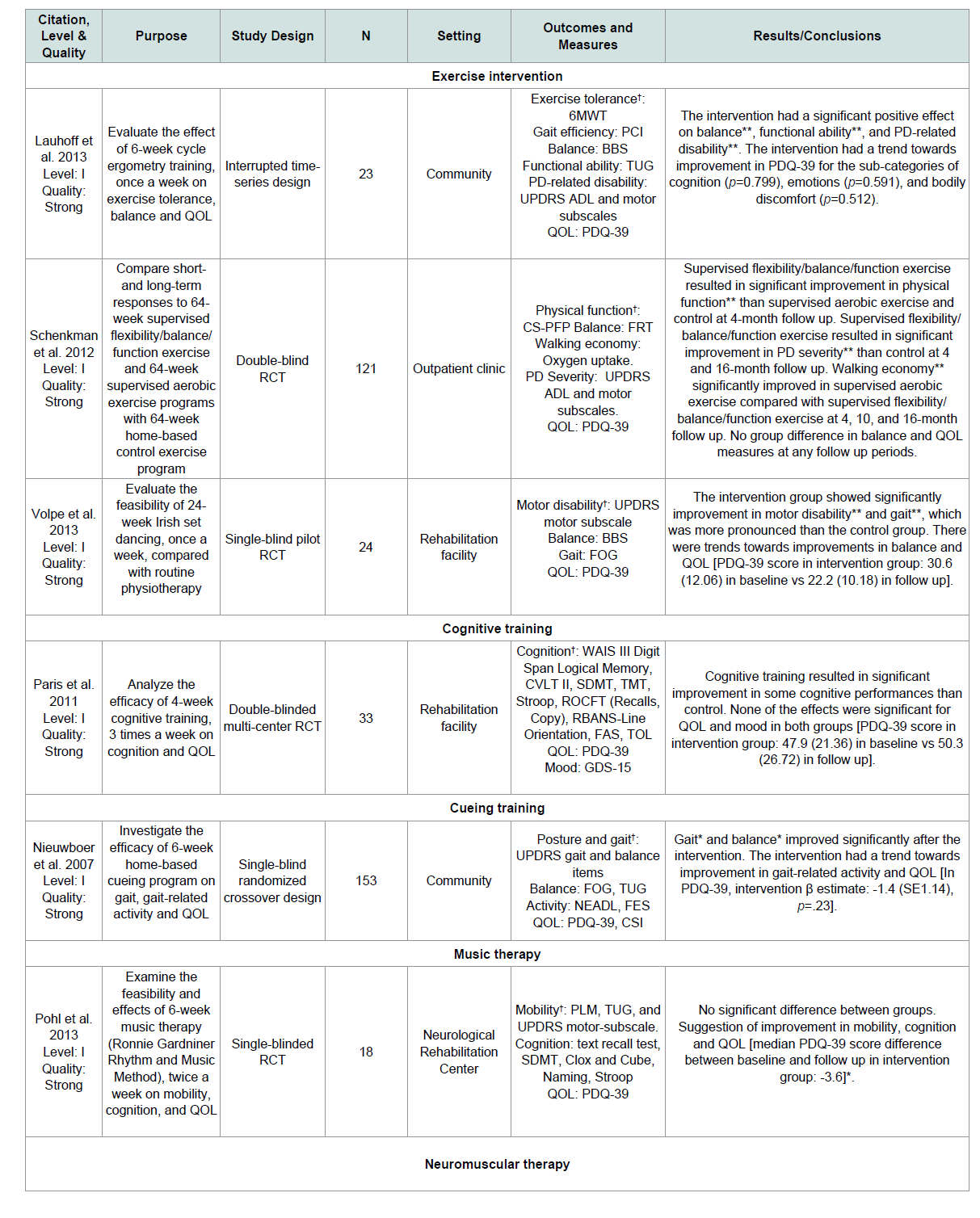

The matrix system by Garrard was used to summarize the eligible studies ( Tables 1 and 2 ) [ 12 ]. Each study was first rated for level of evidence: Level I (RCT or experimental) or Level II (quasiexperimental). Next, three authors (SA, YC, and TB) independently assessed the quality of each study using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. The EPHPP has 6 categories, including selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection method, and withdrawals. Each category is graded as ‘strong’, ‘moderate’ or ‘weak’ [ 13 ]. The category ratings were combined to generate an overall quality rating as: strong quality (no weak rating among the six categories), moderate quality (one weak rating), or weak quality (two or more weak ratings). The ratings agreed by at least two authors were assigned as the final overall quality rating for each study.

Results

The studies were conducted in several countries, including France (n=1), Iran (n=1), Australia (n=1), Spain (n=1), Sweden (n=1), Turkey (n=1), Ireland (n=1), Belgium (n=1), Italy (n=1), United Kingdom (n=1), Brazil (n=3), Netherlands (n=4), and the United States (n=9). Twenty studies have Level I evidence and six Level II evidence. Thirteen of the 26 studies (50%) were rated with strong quality, 4 (15%) with moderate quality, and 9 (35%) with weak quality ( Tables 1 and 2 ). In the following sections, we described the types of interventions tested, the QOL instruments used, and the effects of the interventions on QOL.

Types of the interventions tested

Fifteen studies (57.7%) tested an exercise intervention [ 14-28 ], and the remaining 11 studies each evaluated a different intervention including acupuncture [ 29 ], neuromuscular electrical stimulation [ 30 ], patient education [ 31 ], reflexology [ 32 ], self-management program [ 33 ], spa therapy [ 34 ], cognitive training [ 35 ], cueing training [ 36 ], music therapy [ 10 ], neuromuscular therapy [ 37 ], and physiotherapy network [ 38 ]. Eighteen of the 26 studies (69.2%) measured QOL asa primary outcome [ 14-20 , 22 , 24 , 25 , 27-34 ], while the remainders measured it as secondary outcomes [ 10 , 21 , 23 , 26 , 35-38 ].

QOL instruments used

Six different QOL instruments were used across the 26 studies. Twenty studies (77%) used the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire 39 (PDQ-39) [ 10 , 17 , 19-27 , 29 , 31-38 ]. The PDQ-39 is a 39-item selfreport questionnaire with a 5-point Likert-type scale, representing 8 domains (Mobility, Activities of Daily Living, Emotional Well-Being, Stigma, Social Support, Cognitions, Communication, and Bodily Discomfort). The PDQ-39 Summary Index (PDQ-39SI) is an overall score and expressed as a percentage ranging from 0 to 100. Lower scores indicate better QOL [ 39 ].

Four studies used the PD QOL scale (PDQL) [ 15 , 16 , 18 , 28 ]. The PDQL is a self-administered questionnaire on a 5-point Likert scale and contains 4 domains (Parkinson Symptoms, Systemic Symptoms, Social Functioning, and Emotional Functioning). Higher scores indicating better perceived QOL [ 40 ].

Two studies used the Swallowing QOL (SWAL-QOL) scale [ 14 , 30 ]. The SWAL-QOL measures swallowing-related QOL, including 44 items. It contains 11 domains, including burden, symptom frequency, food selection, eating duration, eating desire, communication, fear, mental health, social functioning, fatigue, and sleep. Higher scores indicates better perceived swalloing-related QOL [ 41 ].

Effects of the interventions on QOL

Fifteen of the 26 studies (58%) showed that the interventions significantly improved QOL [ 10 , 14-16 , 18-20 , 22 , 28-30 , 32-34 , 37 ], while the remaining 11 studies (42%) reported no effect [ 17 , 21 , 23-27 , 31 , 35 , 36 , 38 ]. Among the 12 different types of interventions tested, exercise intervention was examined by 15 studies and the other 11 interventions were only tested by one study.

Exercise intervention

Twelve of the 15 exercise studies treated QOL as a primary outcome ( Table 1 ): 8 studies are level I evidence [ 16-19 , 22 , 25 , 27 , 28 ], and 4 are level II evidence [ 14 , 15 , 20 , 24 ]. Seven studies (58%) have weak quality [ 14 , 15 , 18-20 , 24 , 25 ] because of the lack of randomizationand blinding, 3 (25%) have moderate quality due to lack of randomization or blinding [ 17 , 27 , 28 ], and 2 (17%) have strong quality [ 16 , 22 ].

The modality of exercise included swallowing exercise [ 14 ], boxing [ 15 , 16 ], physiotherapist-supervised exercise [ 18 ], high intensity resistance exercise [ 19 ], combined strength, endurance, and/or balance exercises [ 17 , 20 , 28 ], Nintendo Wii [ 22 ], Nordic walking [ 24 ], Ai-Chi [ 25 ], and dance [ 27 ]. The duration of exercise interventions varied from 4 weeks [ 22 ], 5 weeks [ 14 ], 6 weeks [ 24 ], 8 weeks [ 27 ], 10 weeks [ 18 , 28 ] to 16 weeks [ 20 ] with 12 weeks as the most used duration [ 15-17 , 19 , 25 ]. The frequency of exercise was 2 [ 17 , 24 , 25 , 27 ], 3 [ 15 , 16 , 18-20 , 22 ], 4 [ 28 ], or 5 times a week [ 14 ]. Eight out of the 12 studies (67%) showed significant improvement in QOL [ 14-16 , 18-20 , 22 , 28 ].

The three exercise studies that treated QOL as a secondary outcome were all level I evidence with strong quality. The durations of the exercise interventions varied from 6 [ 21 ] to 24 [ 26 ] and 64 weeks [ 23 ]. However, none of these studies showed an effect on QOL ( Table 2 ).

Acupuncture

One study investigated the effect of a weekly acupuncture therapy with massage for 6 months on QOL as a primary outcome ( Table 1 ). This study is level II evidence and has weak quality due to the lack of randomization and blinding. QOL was significantly improved at 6 months compared to baseline [ 29 ].

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation

A study tested the effect of 3-5 weeks of adjuvant neuromuscular electrical stimulation, 5 times a week on QOL as a primary outcome [ 30 ]. This study is level I evidence and has strong quality. All groups improved their QOL over time with minimal group differences( Table 1 ).

Patient education

One study evaluated the effect of 8 weekly sessions of the Patient Education Program Parkinson (PEPP) on QOL [ 31 ]. This study is level I evidence and has moderate quality. Compared to the control group, PEPP showed a trend towards significance on QOL, a primary outcome ( Table 1 ).

Reflexology

One study examined the effect of 8 reflexology treatments (acupressure) on QOL as a primary outcome [ 32 ]. This study is level II evidence and has weak quality due to the lack of randomization and blinding. The results showed within-group improvement in QOL, but not between-group differences ( Table 1 ).

Self-management program

A self-management program was tested using 2 different doses of 18 hours and 27 hours over 6 weeks for its effect on QOL as a primary outcome [ 33 ]. This study is level I evidence and has strong quality. Compared to a control group, both doses improved QOL significantly ( Table 1 ).

Spa therapy

One study evaluated the effect of a 3-week daily spa therapy (thermal baths, drinking mineral water, various types of showers, and underwater massage) on QOL as a primary outcome ( Table 1 ). This study is level I evidence and has strong quality. Spa therapy improved QOL significantly compared to control [ 34 ].

Cognitive training

One study tested the effect of interactive multimedia and paperand- pencil-based cognitive training program, 3 times a week for 4 weeks on QOL as a secondary outcome [ 35 ]. This study is level I evidence and has strong quality. The results showed that cognitive training had no significant effect on QOL ( Table 2 ).

Cueing training

One study tested the effect of a 6-week cueing training that contains 3 rhythmical cueing modalities (auditory, visual, and somatosensory) on QOL as a secondary outcome [ 36 ]. This study is level I evidence and has strong quality. The results showed that cueing training had no significant effect on QOL ( Table 2 ).

Music therapy

One study tested the effect of a 6-week, twice a week music therapy that contains stretching and some rhythmical movements on QOL as a secondary outcome [ 10 ]. This study is level I evidence and has strong quality. The results indicated that music therapy significantly improved QOL ( Table 2 ).

Neuromuscular therapy

One study examined the effect of a 4-week, twice a week neuromuscular therapy on muscle pain and spasm (primary outcomes) as well as QOL (secondary outcome) [ 37 ]. This study is level I evidence and has strong quality. The results indicated that QOL improved over the 4-week period for the intervention group, but there was no significant difference between the 2 groups ( Table 2 ).

Physiotherapy network

Munneke et al. used a physiotherapy network namedParkinsonNet to train physiotherapists and facilitate communicationbetween health professionals and persons with PD ( Table 2 ). This study is level I evidence and has strong quality. Compared to the control group, ParkinsonNet did not show effects on improving QOL, a secondary outcome [ 38 ].

Discussions

The main findings from our review are that 77% of the 26 included studies represented ‘Level I’ (RCT or experimental designs) and 23% ‘Level II’ (quasi-experimental designs) evidence. About 50% of the studies have ‘strong quality’, 15% ‘moderate quality’ and 35% ‘weak quality’. The main reasons for moderate or weak quality were the lack of randomization and blinding.

Eighteen of studies (69%) tested the intervention effects on QOL as a primary outcome and 8 (31%) of studies treated QOL as a secondary outcome. In addition, a variety of non-pharmacological interventions have been tested, including exercise, acupuncture, neuromuscular electrical stimulation, patient education, reflexology, self-management program, spa therapy, cognitive training, cueing training, music therapy, neuromuscular therapy, and physiotherapy network. Except for 15 studies that evaluated an exercise intervention, only one study tested each one of the other 11 interventions.

The findings from our review suggest that 8 (53%) exercise intervention studies indicated that exercise were effective at improving QOL in PD in contrast to findings from the other 7 (47%) including three studies measuring QOL as a secondary outcome. The discrepant findings seem to be influenced by several factors: 1) whether QOL was treated as a primary or secondary outcome: Studies that treated QOL as a primary outcome were more likely to have a sufficient large sample size and adequate power to detect a significant effect on QOL, whereas studies that evaluated QOL as a secondary outcome were not even if they were well designed; 2) the intervention mode and dose: There were substantial variations in the mode and dose of the exercise interventions across studies [ 14-28 ]. The dose-response relationships between exercise and QOL in PD have not been studied; 3) confounding factors: The intervention effects were further affected by sample characteristics, making the study findings less comparable. For example, the PD stages, duration, and drug regimen were quite heterogeneous across studies.

Furthermore, combined exercise may be more promising than a single mode exercise intervention. One study showed that 6-week music therapy combined with rhythmical dance of an hour, twice a week dose improved QOL [ 10 ]. Recently, dance programs like tango have been introduced [ 42 , 43 ], showing increased social contacts and cognition over time. These results suggest that music with physical movements can improve non-motor symptom (e.g., cognition) better than either component alone, which needs to be further tested in research with an aim to enhance QOL.

There are emerging but very limited evidence about the effects of other non-pharmacological interventions on QOL in persons with PD. Spa therapy [ 34 ], neuromuscular therapy [ 37 ], reflexology [ 32 ], and acupuncture [ 29 ] induced significant improvements of QOL in persons with PD. All these studies included a massage as an intervention element, but each study used a different PD sample: Spa therapy (n=31, mean age=67, mean PD duration=12 years), neuromuscular therapy (Intervention group: n=18, mean age=62, mean Hoehn & Yahr score=1.8), reflexology (n=16), and acupuncture (n=25, mean age=69, mean PD duration=6 years, mean UPDRS motor-subscale=24). Their findings are furtherlimited because the reflexology [ 32 ] and acupuncture [ 29 ] used quasi-experimental designs without a control group. Furthermore, neuromuscular electrical stimulation [ 30 ], and self-management intervention improved QOL [ 33 ]. However, cognitive training [ 35 ], physiotherapy networks intervention [ 38 ], and patient education [ 31 ] did not show any benefits to PD symptoms and QOL. Similar to the findings of exercise studies, the results of these non-pharmacological interventions were likely affected by its design of considering QOL as a primary or secondary outcome.

Strengths and Limitations

This review has two notable strengths. First, it comprehensively examined the non-pharmacological interventions and their effects on QOL in persons with PD. Second, it used a strong method of conducting the literature search and review. This review is limited by the scope of literature search. We only searched three databases (PubMed, CINAHL and PsycINFO) where non-pharmacological interventions are most likely published. Although we did perform manual literature search via cross-referencing, it is possible that we have missed some relevant publications.

Implications for Research and Practice

Given the fact that only one study met the eligibility criteria for 11 of the 12 non-pharmacological interventions, there is a pressing need to increase the sheer volume of experimental studies to test out these interventions. Our findings suggest that randomization and blinding are the two major factors to consider in order improving the study quality. Future studies need to balance internal validity and generalizability. For example, limiting the study sample to early stage PD improves the sample homogeneity and internal validity, but reduces the generalizability of study findings to other Parkinson’s stages. Design considerations are essential in future studies to help determine the minimally effective and optimal doses of the nonpharmacological interventions. Future research should build on this literature to further refine the interventions and test the minimallyeffective and optimal doses as well as the dose-response relationships of each intervention for improving QOL across different stages of PD.

Despite the methodological concerns about existent studies, emerging evidence supports that non-pharmacological interventions likely play a role in improving QOL in persons with PD in clinical practice. Clinicians should become aware of the variety of nonpharmacological interventions and use a person-centered and ailored approach to select the non-pharmacological interventions and their doses most suitable to the patient at hand.

Conclusion

QOL is increasingly recognized as an essential outcome in PD intervention research. A variety of non-pharmacological interventions is potentially effective on improving quality of life and has been studied by at least one experimental study. Exercise is the most examined intervention. There is emerging evidence that other non-pharmacological interventions are potentially promising for improving QOL, but research is very limited currently. Little is known about the minimally effective and optimal doses of the nonpharmacological interventions.

Acknowledgement

The conception and initial development of this work was supported by the Edmond J. Safra Visiting Nursing Faculty Program award from the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation that was awarded to TB and FY. This work was also supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health Award Number 1R01AG043392-01A1 awarded to FY. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Pringsheim T, Jette N, Frolkis A, Steeves TD (2014) The prevalence of Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord 29: 1583-1590.

- American Parkinson Disease Association (2015) Understanding the basics of PD.

- Parkinson’s Disease Foundation (2016) Statistics on Parkinson’s.

- Beitz JM (2014) Parkinson's disease: a review. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 6: 65-74.

- Fritsch T, Smyth KA, Wallendal MS, Hyde T, Leo G, et al. (2012) Parkinson disease: research update and clinical management. South Med J 105: 650-656.

- Lee J, Choi M, Jung D, Sohn YH, Hong J (2015) A structural model of health-related quality of life in Parkinson's Disease patients. Western J Nurs Res 37: 1062-1080.

- Foppa AA, Chemello C, Vargas-Pelaez CM, Farias MR (2016) Medication therapy management service for patients with Parkinson's disease: A before-and-after study. Neurol Ther 5: 85-99.

- Salat D, Tolosa E (2013) Levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson's disease: current status and new developments. J Parkinsons Dis 3: 255-269.

- Stacy M (2009) Medical treatment of Parkinson disease. Neurol Clin 27: 605-631.

- Pohl P, Dizdar N, Hallert E (2013) The Ronnie Gardiner Rhythm and Music Method - a feasibility study in Parkinson's disease. Disabil Rehabil 35: 2197-2204.

- 11.Uitti RJ (2012) Treatment of Parkinson's disease: focus on quality of life issues. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 18 Suppl 1: S34-S36.

- Garrard J (2010) Health sciences literature review made easy: The matrix method, (3rdedn). Jones & Bartlett Publishers, Massachusetts, USA.

- Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S (2004) A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 1: 176-184.

- Argolo N, Sampaio M, Pinho P, Melo A, Nobrega AC (2013) Do swallowing exercises improve swallowing dynamic and quality of life in Parkinson's disease? NeuroRehabilitation 32: 949-955.

- Combs SA, Diehl MD, Staples WH, Conn L, Davis K, et al. (2011) Boxing training for patients with Parkinson disease: a case series. Phys Ther 91: 132-142.

- Combs SA, Diehl MD, Chrzastowski C, Didrick N, McCoin B, et al. (2013) Community-based group exercise for persons with Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled trial. NeuroRehabilitation 32: 117-124.

- Cruise KE, Bucks RS, Loftus AM, Newton RU, Pegoraro R, et al. (2011) Exercise and Parkinson's: benefits for cognition and quality of life. Acta Neurol Scand 123: 13-19.

- Dereli EE, Yaliman A (2010) Comparison of the effects of a physiotherapist-supervised exercise programme and a self-supervised exercise programme on quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease. Clin Rehabil 24: 352-362.

- Dibble LE, Hale TF, Marcus RL, Gerber JP, LaStayo PC (2009) High intensity eccentric resistance training decreases bradykinesia and improves Quality Of Life in persons with Parkinson's disease: a preliminary study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 15: 752-757.

- Kelly NA, Ford MP, Standaert DG, Watts RL, Bickel CS, et al. (2014) Novel, high-intensity exercise prescription improves muscle mass, mitochondrial function, and physical capacity in individuals with Parkinson's disease. J Appl Physiol (1985) 116: 582-592.

- Lauhoff P, Murphy N, Doherty C, Horgan NF (2013) A controlled clinical trial investigating the effects of cycle ergometry training on exercise tolerance, balance and quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease. Disabil Rehabil 35: 382-387.

- Pedreira G, Prazeres A, Cruz D, Gomes I, Monteiro L, et al. (2013) Virtual games and quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: A randomised controlled trial. Adv Parkinsons Dis 2: 97-101.

- Schenkman M, Hall DA, Baron AE, Schwartz RS, Mettler P, et al. (2012) Exercise for people in early- or mid-stage Parkinson disease: a 16-month randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther 92: 1395-1410.

- Van Eijkeren FJ, Reijmers RS, Kleinveld MJ, Minten A, Bruggen JP, et al. (2008) Nordic walking improves mobility in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 23: 2239-2243.

- Villegas IL, Israel VL (2014) Effect of the Ai-Chi method on functional activity, quality of life, and posture in patients with Parkinson Disease. Topics Geriatr Rehabil 30: 282-289.

- Volpe D, Signorini M, Marchetto A, Lynch T, Morris ME (2013) A comparison of Irish set dancing and exercises for people with Parkinson's disease: a phase II feasibility study. BMC Geriatr 13: 54.

- Westheimer O, McRae C, Henchcliffe C, Fesharaki A, Glazman S, et al. (2015) Dance for PD: a preliminary investigation of effects on motor function and quality of life among persons with Parkinson's disease (PD). J Neural Transm (Vienna) 122: 1263-1270.

- Yousefi B, Tadibi V, Khoei AF, Montazeri A (2009) Exercise therapy, quality of life, and activities of daily living in patients with Parkinson disease: a small scale quasi-randomised trial. Trials 10: 67.

- Eng ML, Lyons KE, Greene MS, Pahwa R (2006) Open-label trial regarding the use of acupuncture and yin tui na in Parkinson's disease outpatients: a pilot study on efficacy, tolerability, and quality of life. J Altern Complement Med 12: 395-399.

- Heijnen BJ, Speyer R, Baijens LW, Bogaardt HC (2012) Neuromuscular electrical stimulation versus traditional therapy in patients with Parkinson's disease and oropharyngeal dysphagia: effects on quality of life. Dysphagia 27: 336-345.

- A'Campo LE, Wekking EM, Spliethoff-Kamminga NG, Le Cessie S, Roos RA (2010) The benefits of a standardized patient education program for patients with Parkinson's disease and their caregivers. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 16: 89-95.

- Johns C, Blake D, Sinclair A (2010) Can reflexology maintain or improve the well-being of people with Parkinson's Disease? Complement Ther Clin Pract 16: 96-100.

- Tickle-Degnen L, Ellis T, Saint-Hilaire MH, Thomas CA, Wagenaar RC (2010) Self-management rehabilitation and health-related quality of life in Parkinson's disease: a randomized controlled trial. Mov Disord 25: 194-204.

- Brefel-Courbon C, Desboeuf K, Thalamas C, Galitzky M, Senard JM, et al. (2003) Clinical and economic analysis of spa therapy in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 18: 578-584.

- Paris AP, Saleta HG, de la Cruz Crespo Maraver M, Silvestre E, Freixa MG, et al. (2011) Blind randomized controlled study of the efficacy of cognitive training in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 26: 1251-1258.

- Nieuwboer A, Kwakkel G, Rochester L, Jones D, van Wegen E, et al. (2007) Cueing training in the home improves gait-related mobility in Parkinson's disease: the RESCUE trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 78: 134-140.

- Craig LH, Svircev A, Haber M, Juncos JL (2006) Controlled pilot study of the effects of neuromuscular therapy in patients with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 21: 2127-2133.

- Munneke M, Nijkrake MJ, Keus SH, Kwakkel G, Berendse HW, et al. (2010) Efficacy of community-based physiotherapy networks for patients with Parkinson's disease: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Neurol 9: 46-54.

- Peto V, Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, Greenhall R (1995) The development and validation of a short measure of functioning and well being for individuals with Parkinson's disease. Qual Life Res 4: 241-248.

- de Boer AG, Wijker W, Speelman JD, de Haes JC (1996) Quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease: development of a questionnaire. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 61: 70-74.

- McHorney CA, Bricker DE, Kramer AE, Resenbek JC, Robbins J, et al. (2000) The SWAL-QOL outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: I. Conceptual foundation and item development. Dysphagia 15: 115-121.

- Foster ER, Golden L, Duncan RP, Earhart GM (2013) Community-based Argentine tango dance program is associated with increased activity participation among individuals with Parkinson's disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 94: 240-249.

- McKee KE, Hackney ME (2013) The effects of adapted tango on spatial cognition and disease severity in Parkinson's disease. J Mot Behav 45: 519-529.