Journal of Geriatrics and Palliative Care

Download PDF

Research Article

*Address for Correspondence: Danforn Lim, Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales,PO Box 3256, Blakehurst, NSW 2221 Australia, E-mail: celim@unswalumni.com

Citation: Ho K, Lim CED, Cheng NCL, Zaslawski C. ACEPAC Study - Australian Chinese patient’s Experiences of Palliative Care Services. J Geriatrics Palliative Care 2014;2(2): 8.

Copyright © 2014 Danforn Lim et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use,distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Geriatrics and Palliative Care | ISSN 2373-1133 | Volume: 2, Issue: 2

Submission: 27 March 2014 | Accepted: 20 May 2014 | Published: 26 May 2014

Knowledge statement: Of 15 statements, mean numbers of correct answers were 11 and 9.12 for the palliative care group and other specialties group respectively (Table 2). An independent t-test was carried out to compare the number of correct answers for two groups. There was a significant difference in mean scores for two groups (p=0.031). The magnitude of the differences in the means (mean difference=1.88, 95% CI: 0.18 to 3.57) was large (eta squared=0.15). In particular, there is a significant difference in the responses for statement 2 between two groups (p=0.019).

Attitudes and experiences on EOLCP, pain management and consultation: Only a small percentage of participants (36%) in other specialities group agreed that only the palliative care team should be responsible after commencement of EOLCP (Table 3). The majority of participants (87.1%) regarded symptom control as the highest priority. Most participants (67.7%) also found pain control complex. Some participants (35.5%) received inadequate support from the pharmacist. However, they were comfortable with seeking support from another doctor (96.8%).

In terms of the prevention for opioid-induced constipation, all participants from palliative care group (100%) prescribed a laxative in addition to an opioid, as compared to a small number of the other group (44%) (p=0.047) (Table 3). Nevertheless, the majority of the subjects (83.9%) would generally prescribe an anti-emetic along with an opioid.

Qualitative: There were 12 subjects for the interview. Three of them were from palliative care, whereas others were from other specialties.

Specialty Trainees’ Understanding of End-of-Life Care Symptom Management and End-of-Life Care Pathway: A Quantitative and Qualitative Pilot Study

Khai Ho1, Chi Eung Danforn Lim1,2*, Nga Chong Lisa Cheng1, and Christopher Zaslawski2

- 1South Western Sydney Clinical School, University of New South Wales, Australia

- 2School of Medical and Molecular Biosciences, University of Technology Sydney, Australia

*Address for Correspondence: Danforn Lim, Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales,PO Box 3256, Blakehurst, NSW 2221 Australia, E-mail: celim@unswalumni.com

Citation: Ho K, Lim CED, Cheng NCL, Zaslawski C. ACEPAC Study - Australian Chinese patient’s Experiences of Palliative Care Services. J Geriatrics Palliative Care 2014;2(2): 8.

Copyright © 2014 Danforn Lim et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use,distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Geriatrics and Palliative Care | ISSN 2373-1133 | Volume: 2, Issue: 2

Submission: 27 March 2014 | Accepted: 20 May 2014 | Published: 26 May 2014

Abstract

Introduction: Lack of knowledge of end-of-life care pathway (EOLCP) and misconceptions about opioid use are detrimental toproviding quality care to patients with life-limiting diseases. This study aims to use the mixed-method to assess the level of specialty trainees’ perceptions regarding EOLCP and symptom management in the Australian context.Methods: A total of 31 accredited college trainees in surgery, obstetrics and gynaecology, emergency medicine, anaesthesia as well as physician trainees who had been rotated to palliative care were recruited for the questionnaire. A total of 12 subjects were recruited for the individual interview.

Results and Discussion: Both quantitative and qualitative data suggested that participants showed a basic understanding of EOLCP and symptom control. Most participants were generally comfortable with opioid use. They were able to recognize the priorities of end-oflife care and common opioid-related side effects. However, additional education on probability of serious side effects related to opioids, opioid rotation, opioid dosage calculation and prophylactic medications, were suggested. Large-scale studies should be conducted to explore the adequacy of end-of-life care education within specific specialty, other potential factors on practice of EOLCP and opioid use, as well as more effective education strategies in the Australian context.

Keywords

End-of-life care, Liverpool care pathway, Opioids, Symptom control, Terminal careIntroduction

In the last decade, palliative care has been developed rapidly as a specialist service, participating in the multidisciplinary team to improve the quality of life for patients with life limiting disease [1]. However, despite a rapid development of palliative care services, the quality of care of the dying is still suggested to be poor at hospitals [2,3]. In order to provide better care for terminal patients, the Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP) was developed by the Royal Liverpool University Trust and the Marie Curie Centre in Liverpool [4]. It has been adapted to replace other documents and being utilized as the end-of-life care pathway (EOLCP) in Australia. It aims to use a structured framework to coordinate and guide the holistic end-of-life care for the dying [5]. It can improve the patient-centered interdisciplinary cooperation and minimizes ambiguities in decision-making for terminally ill patients [4,6]. Although the recent Cochrane review questioned the evidence supporting LCP [7], two recent reviews have shown that practice of EOLCP contributed to an improved overall care of terminal patients and encouraged healthcare professionals to use the gold standards of care in the general healthcare settings [8,9].To date, there are only a limited number of quantitative and qualitative studies on exploring doctors’ understandings of end-oflife care. One early U.S. SUPPORT study has identified problems with communication, frequency of aggressive treatment and characteristics of hospital death in end-of-life care setting [10]. Only less than half of participating physicians knew when their patients did not prefer CPR. Also, 46% of do-not- resuscitate orders were documented only within two days of death [10]. Another quantitative U.S. study identified physicians’ inadequate understanding in proper pain assessment and pharmacological properties of opioids [11].

Symptomatic control, such as pain relief, is an essential part of EOLCP [12]. Several quantitative studies investigated the level of knowledge for pain management in end-of-life care settings. The majority of studies done in the 1990s revealed a significant gap in physicians’ knowledge of pain management [11,13-15]. Main issues include inadequate fundamental knowledge of opioid use, including drug choices and inappropriate concerns about side effects [11,13-17]. However, there were few qualitative studies done in this field. One qualitative study done in the U.S. found that surgeons often relied on palliative care consultations to manage pain and non-pain symptoms [18]. The most recent qualitative study was done in New Zealand and revealed that only nearly half of the physicians were confident to provide adequate symptomatic management for end-of-life patients [19]. There was no mixed-method study identified during literature review. Therefore, the primary aim of this study is to use the mixedmethod to assess the level of specialty trainees’ perceptions regarding EOLCP and symptom management in the Australian context.

Methods

Selection and description of participantsThis was a single hospital-based pilot study at Liverpool hospital, Sydney, Australia. Accredited college trainees in surgery, obstetrics and gynaecology (O&G), emergency medicine, anaesthesia as well as physician trainees who had been rotated to the palliative care (PC) team were recruited. All the interviewees will be the accredited trainees for their respective Royal Colleges ie., RACS, RANZCOG, ACEM, RANZCA, and RACP. None of the RACP trainees in this interview were enrolled into the AChPM (Australasian Chapter of Palliative Medicine) training program ie., none of them is an advanced specialty trainee in Palliative medicine. Where informed consent was not obtained, the participant would be excluded from our study.

Study design: The mixed-method was used in this study and expected to provide more insights into trainees’ understandings of end-of-life care. After informed consent was obtained, a questionnaire was given to assess their perceptions of end-of-life care pathway and attitudes towards symptom management using pain management as the main example. The questionnaire was modified from the survey used by Rurup et al. [17] after the permission was obtained. Statements regarding euthanasia which were inappropriate in the Australian context were removed whereas questions on EOLCP were added. The first part of the questionnaire explored their background characteristics, followed by a series of knowledge statements. These statements were mainly in true or false format. The second part of the questionnaire referred to their attitudes and experiences with end-of-life care. Attitudes questions provided participants with five answers: “completely agree”, “partially agree”, “neutral”, “partially disagree” and “completely disagree”. Frequency was used for experience statements, including none”, “seldom”, “sometimes”, “often” and “all the time”. Two selfassessment questions with a numerical scale were used to determine differences in self-perceived knowledge scores between pre- and post-questionnaire. Each participant received a voucher at a value of $3.70 for use at the local coffee shop as an appreciation for their involvement.

The mixed-method was used in this study and expected to provide more insights into trainees’ understandings of end-of-life care. After informed consent was obtained, a questionnaire was given to assess their perceptions of end-of-life care pathway and attitudes towards symptom management using pain management as the main example. The questionnaire was modified from the survey used by Rurup et al. [17] after the permission was obtained. Statements regarding euthanasia which were inappropriate in the Australian context were removed whereas questions on EOLCP were added. The first part of the questionnaire explored their background characteristics, followed by a series of knowledge statements. These statements were mainly in true or false format. The second part of the questionnaire referred to their attitudes and experiences with end-of-life care. Attitudes questions provided participants with five answers: “completely agree”, “partially agree”, “neutral”, “partially disagree” and “completely disagree”. Frequency was used for experience statements, including none”, “seldom”,“sometimes”, “often” and “all the time”. Two selfassessment questions with a numerical scale were used to determine differences in self-perceived knowledge scores between pre- and post-questionnaire. Each participant received a voucher at a value of $3.70 for use at the local coffee shop as an appreciation for their involvement. Doctors who indicated their willingness for interviews in the questionnaire were recruited. The interview consisted of both theoretical and practical questions. Main topics included general understandings of end-of-life care and EOLCP, pain management and opioid use, as well as current education and resources on this area. One researcher was present at the interview. After the informed consent was obtained, interviews were recorded and converted into transcripts for evaluation.

Statistics

Quantitative: Data analysis was carried out through IBMTM SPSS Statistics 20.0. Results were separated into two groups: palliative care group and other specialties group. Palliative care group refers to physician trainees who had been rotated through palliative care term, whereas other specialties group refers to those who had not received specific palliative care education. For knowledge statement, any missing responses were considered as wrong answers. Regarding attitudes and experiences questions, answers “completely agree” and “partially agree” were merged into one category “agree”, whereas answers “completely disagree” and “partially disagree” were grouped into the category “disagree”. For frequency questions, “all the time”, “often” and “sometimes” were categorised into one group where as “seldom” and “none” were merged into another category. The missing figures for these questions were excluded from the total calculation during data analysis.

An independent t-test was utilised to compare mean scores of correct answers between palliative care group and other specialities group. A significance level of p.

Qualitative: The transcripts of interviews were analysed using the NVivo 10. Methodological triangulation was used to increase the validity of this study [20]. Conventional content analysis was utilised to evaluate the data [21]. Different themes were set according to pre-defined interview questions. Coding for common opinions under each theme was utilised to explore the general perceptions of participants in this study. All results were de-identified for analysis.

Ethical consideration

This study was ethically approved by The Biomedical Human Research Ethics Advisory Panel at The University of New South Wales, Australia and South Western Sydney Local Health District, NSW, Australia.

Results

QuantitativeResponse rate: The questionnaire was sent out to 36 potential participants. 31 questionnaires were returned for analysis (total response rate 86%). The main reported reason for not participating was that they were too busy with work.

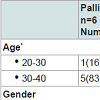

Background characteristics: Table 1 shows the background characteristics of participants. The mean values for self-rated score before and after completing the questionnaire were 5.3 and 5.067 respectively. About half of the participants (51.6%) indicated that current education on pain management was adequate. Most of them used opioids often with 80.6% of them prescribing opioids to above 50 participants in 2011. Terminally ill patients treated by palliative care trainees were prescribed opioids more often than those who were treated by other speciality trainees.

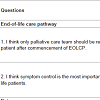

Knowledge statement: Of 15 statements, mean numbers of correct answers were 11 and 9.12 for the palliative care group and other specialties group respectively (Table 2). An independent t-test was carried out to compare the number of correct answers for two groups. There was a significant difference in mean scores for two groups (p=0.031). The magnitude of the differences in the means (mean difference=1.88, 95% CI: 0.18 to 3.57) was large (eta squared=0.15). In particular, there is a significant difference in the responses for statement 2 between two groups (p=0.019).

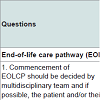

Attitudes and experiences on EOLCP, pain management and consultation: Only a small percentage of participants (36%) in other specialities group agreed that only the palliative care team should be responsible after commencement of EOLCP (Table 3). The majority of participants (87.1%) regarded symptom control as the highest priority. Most participants (67.7%) also found pain control complex. Some participants (35.5%) received inadequate support from the pharmacist. However, they were comfortable with seeking support from another doctor (96.8%).

In terms of the prevention for opioid-induced constipation, all participants from palliative care group (100%) prescribed a laxative in addition to an opioid, as compared to a small number of the other group (44%) (p=0.047) (Table 3). Nevertheless, the majority of the subjects (83.9%) would generally prescribe an anti-emetic along with an opioid.

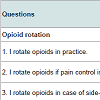

Attitudes and experiences concerning opioid use: The majority of participants rotated opioids when pain control was inadequate (93.5%) or when side effects occurred (90.3%). However, most trainees (87.1%) found it difficult to calculate opioid dosages when rotating them. There was a significant difference in the responses between two groups regarding opioid tolerance (p=0.043). Only a small number of palliative care trainees (33.3%) experienced that tolerance hampers the analgesic effects of opioids, as compared to a majority of trainees from other specialities (84%). However, most participants in both groups (71%) encountered the situation when patients’ fear of addiction compromised the effects of opioids (Table 4).

Qualitative: There were 12 subjects for the interview. Three of them were from palliative care, whereas others were from other specialties.

Theme 1: End of life care pathway (EOLCP): The interviews provided some insight into perceptions of end-of-life care. Seven out of fifteen subjects directly expressed their views on end-of-life care in general. Although all of them regarded end-of-life care as a critical aspect of medical care, all registrars from other specialties had never been involved before. Thus, their understandings of EOLCP were limited as compared with palliative care registrars, as illustrated by one of the untrained registrars:

“There is a pathway. There are protocols. There are certain forms which we have to fill in, certain kind of communications...Like I really don’t know how the protocol is, how you follow the protocol, what exactly you do...”

Theme 2: Priorities for end of life care: Personal preference was suggested by two registrars to be the most important priority, as the following comment illustrates:

“It essentially depends on patients’ own priorities because the patient may favour other things. They may favour that they are not given medication which alters their cognitive function, which might be given in end-of-life care. And if the patient so wishes instead of comfort, I think we should respect that.”Symptomatic relief was mentioned by ten participants. Three registrars also prioritised dignity and quality of life of the patient. All the priorities mentioned during interviews were interrelated to each other, as mentioned by one of the ED registrars:

“...Changing the orientation of your management from being one trying to treat the illness to treating their symptoms and making them comfortable and the hope being in my sense, a more dignified death...”

Theme 3: Prescribing opioids: Two participants directly expressed their views on opioids. Both of them acknowledged the importance of opioids and were quite comfortable with opioid use, as illustrated by one of the palliative care registrars:

“I think opioids generally are good drugs because they are very potent. You can, when you use appropriately, you can settle the patient’s pain.

”Three participants believed that there was no difference in management protocols despite the context. Nine subjects indicated that there were slight differences in prescribing patterns for a terminally ill patient compared to prescribing opioids to other patients. These include relatively higher doses, different modes, frequencies and time factor. Less reservation of the dose due to a different goal was one of the main differences, as commented by one of the O&G registrars:

“The difference is in like, what are you trying to achieve, are you giving a full day pain relief to the patient. That’s how you give the frequency. The mode of how you ask them to take it.

”Theme 4: Concerns regarding opioids: Side effects, contraindications and allergies were main concerns of participants when they were prescribing opioids. The most common side effects they encountered included nausea, vomiting and constipation. Other side effects included itching, anaphylactic reactions, more seriously but rarely respiratory depression, cognitive depression, sedation and drowsiness.

All participants were not unduly concerned about addiction or tolerance when prescribing opioids. They prioritised pain control over their concerns regarding possible addiction or tolerance, as demonstrated by one of the ED registrars.

“If they’sve got drug addiction or dependency, but it doesn’t mean that they can’st have pain. My preference is to treat them.”Another common concern was the differentiation between opioid-induced symptoms and disease-induced symptoms, as expressed by one of the surgical registrars:

“...Sometimes there is a concern opioids make people drowsy because in neurosurgery. We have patients, we say head injuries, brain tumours etc., where it is important to assess their neurological functions, then it’ss yes. And so if opioids make them drowsy, then we don’st know if it’ss because of the drugs that make them drowsy, or because of something intracranial. So there is a concern from that point of view.”

One of participants also suggested concerns from the family and other staff, as illustrated by her comment:

“There are usually questions from the relatives, or even the staff sometimes that is it going to be dependent...are we creating more symptoms, like constipation and staff for the patient and making his life difficult and not actually solving the problem, those are the kind of things...”

Theme 5: Current education and resources: The majority of participants suggested that it was necessary to improve the education on end-of-life care (Figure 1). Ten participants believed that current education on end-of-life care for medical trainees were inadequate, as commented by one of the participants:

“...but it’s not something that we get formal education on as much as we do other things. So it’s probably not enough, to be honest, but it’ss not a criticism, it’ss certainly things that need to be educated on...

”The other two participants suggested that the education and resources were provided and easily accessible but not well appreciated, as illustrated by his comments:

“I guess it’s there. And you can go to course and there are very active people who like to teach you... maybe in these two years, I might have plenty of possibilities to go to courses if I just look for it. But it’ss most likely not seen as one of the sexy courses to go to.

”Some suggestions were made regarding how to improve the education on this area. Main ones include delivery of essential concepts of end-of-life care to medical students, several learning sessions for interns and residents, as well as regular education sessions on relevant topics for each specialty. One of the palliative care registrars provides a valuable point:

“I think the philosophy behind palliative care should try to get across so that as interns they are in emergency and they come across the patient, they don’st automatically just write them off, they think ok, now, palliative care is not about leading them to die, it’ss just about giving them treatment to make it, to improve their quality of life for how long they have left.”

Discussion

Our data suggested a change in prescribing pattern. Both quantitative and qualitative data suggested that most of our participants were not reluctant to use opioids. One previous study identified the reluctance to opioid use in a significant number of their participants [11]. Our participants were rotating opioids more frequently in case of ineffectiveness or side effects, as compared with the previous similar study [17]. These results may suggest an improved acceptance and understanding of opioids among physicians in recent years. However, the majority of participants showed their weakness in dosage calculation when rotating opioids. This issue suggest the necessity of additional education and more specific training.Both quantitative data and qualitative data demonstrated the adequate understandings of common opioid- induced side effects among participants. Most participants recognised the most common opioids-induced side effects, including nausea, vomiting and constipation [22]. However, most of them indicated in the questionnaire that they usually combined an opioid with an antiemetic. In fact, prophylactic anti-emetics with the commencement of opioid are not required since opioid-induced nausea is usually temporary. Anti-emetics are necessary only when the patient experiences substantial nausea and vomiting [23]. Interestingly, there was a significant difference between groups in terms of laxative use (p=0.047). All palliative care registrars indicated that they would prescribe such a combination. This could be attributed to the fact that constipation is the most common side effect related to chronic opioid use, prophylactic laxatives are essential in palliative setting [23].

Our qualitative data also suggested that specialty trainees had a basic understanding of priorities for terminally ill patients. They prioritised personal preference, symptomatic relief, dignity and quality of life in end-of-life care settings. Thus they recognised the transition of the goal of the treatment from curing to maintaining patient’s comfort. This result was consistent with the previous study. They suggested that the vast majority of providers (95-99%) acknowledged the importance of an adequate pain control [13].

Unwarranted concerns about opioid use were also shown from the quantitative data. Around 3 in 4 participants consider respiratory depression as real danger when they are titrating opioids to control pain. This result is not consistent with the previous Dutch study, which showed the majority of their participants did not have such a concern [17]. It is important for Australian clinicians to understand that use of opioid for moderate to severe pain is quite safe with 0.5% or less respiratory depression events [24]. They also need to realise that respiratory depression can be prevented by appropriate monitoring [25].

Regarding tolerance, there was a significant difference in responses between two groups (p=0.043). The majority of trainees (84%) from other specialities experienced that tolerance related to opioids use compromised opioid efficacy, as compared to palliative care trainees (33.3%). This could be due to the fact that most of palliative care trainees often rotated opioids in practice, as indicated by quantitative data. Opioid rotation may overcome tolerance problems if incomplete cross-tolerance favours analgesia more than side effects [26]. Physicians from other specialities may need to learn to rotate opioids appropriately in order to overcome the tolerance developed when patients are receiving opioids. Although tolerance was sometimes an issue for most trainees from other specialities, all participants indicated that they did not unduly worry about tolerance or addiction issues when prescribing opioids. This finding was inconsistent with previous studies [10,19,20]. This could be attributed to the fact that mixed-method encouraged participants to clarify their answers in more depth rather than constrain their views by predefined categories.

Around 3 in 4 participants experienced patients’ own fear of addiction in practice. During the interview, one participant also mentioned his experience with concerns of addiction from patients and their family. Addiction to opioids is a common myth that can compromise the outcome of pain control [27]. This result is consistent with previous studies [28,29]. Such a concern is unnecessary since opioids are effective and relatively safe with appropriate use and close monitoring [30]. This misconception can be overcome by open patient-provider discussion [29]. Physicians need to recognize this issue and apply appropriate approaches to resolve concerns of patients and their family, thus optimizing the outcome of symptom relief.Additional education of end-of-life care was suggested by both quantitative and qualitative data. The mean score of trained participants was significantly higher than that of untrained participants (p=0.031). This result is consistent with the results from previous studies [11,31-33]. It suggests that training plays a critical role in enhancing the level of knowledge on end-of-life care. Several suggestions on improvement were made during interviews. Possible solutions include learning sessions for interns and residents, as well as regular education on relevant topics for each department. Nevertheless, the study done by Wells et al. [34] suggested that regular education sessions were inadequate whereas other methods including case presentations and short discussion on immediate and specific problems were more effective. Therefore the most appropriate education strategies in the Australian context should be explored in order to improve the understanding of end-of-life care among physicians and enhance the utilization of available resources.

Limitations

One limitation of this study is its small sample size. All subjects came from a single hospital. Thus the results may not necessarily represent the situation in entire Australia. Additionally, not all aspects on this field were explored. Other aspects that may be worthwhile investigating include physicians’ fear of potential audit and regulation regarding opioid use as well as more effective education strategies which are suitable in the Australian context [13,34]. Potential discrepancies between participants’ self-reported behaviors and their actual preferences were also a limitation.Conclusion

The level of clinicians’ basic knowledge seems to have improved over time since 1990s. However, more training about clinical use of opioids is required in Australia, including its dosage calculation, understanding of possibility of serious opioid- induced side effects as well as conjoint use of the prophylactics. Also, clinicians should address patients’ concerns about opioids and resolve them effectively by applying appropriate strategies such as improved communication. Large-scale studies should be conducted to investigate and compare the level of understandings within the groups of other specialties in order to identify the adequacy of end-of-life care education in specific specialty. Other potential factors that may alter the practice of EOLCP and prescription of opioids should also be investigated, such as physicians’ fear of potential audit and regulation on opioid use. In addition, future studies should also be conducted to explore more effective education strategies in the Australian context in order to adequately enhance quality of end-of-life care delivered to terminally ill patients.Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank staff for their participation and palliative care department at Liverpool hospital, Sydney for supporting this project.References

- Norton CK, Hobson G, Kulm E (2011) Palliative and end-of-life care in the emergency department: guidelines for nurses. J Emerg Nurs 37: 240-245.

- Hanratty B, Hibbert D, Mair F, May C, Ward C, et al. (2006) Doctors' understanding of palliative care. Palliative Medicine 20: 493-497.

- Mills M, Davies HT, Macrae WA (1994) Care of dying patients in hospital. BMJ 309: 583-586.

- Zhou G, Stoltzfus JC, Houldin AD, Parks SM, Swan BA (2010) Knowledge, attitudes, and practice behaviors of oncology advanced practice nurses regarding advanced care planning for patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 37: E400-410.

- Clark JB, Sheward K, Marshall B, Allan SG (2012) Staff perceptions of end-of-life care following implementation of the liverpool care pathway for the dying patient in the acute care setting: a New Zealand perspective. J Palliat Med 15: 468-473.

- Anderson A, Chojnacka I (2012) Benefits of using the Liverpool Care Pathway in end of life care. Nurs Stand 26: 42-50.

- Chan R, Webster J (2010) End-of-life care pathways for improving outcomes in caring for the dying. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

- Ellershaw J, Dewar S, Murphy D (2010) Spotlight: Palliative Care Beyond Cancer Achieving a good death for all. British Medical Journal 341: 644-662.

- Phillips JL, Halcomb EJ, Davidson PM (2011) End-of-life care pathways in acute and hospice care: an integrative review. J Pain Symptom Manage 41: 940-955.

- Investigators TSP (1995) A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). JAMA 274: 1591-1598.

- Vonroenn JH, Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK, Pandya KJ (1993) Physician attitudes and practice in cancer pain management- A survey from the eastern-cooperative-oncology-group. Ann Intern Med 119: 121-126.

- Weiss SC, Emanuel LL, Fairclough DL, Emanuel EJ (2001) Understanding the experience of pain in terminally ill patients. Lancet 357: 1311-1315.

- Furstenberg CT, Ahles TA, Whedon MB, Pierce KL, Dolan M, et al. (1998) Knowledge and attitudes of health-care providers toward cancer pain management: A comparison of physicians, nurses, and pharmacists in the state of New Hampshire. J Pain Symptom Manage 15: 335-349.

- Elliott TE, Murray DM, Elliott BA, Braun B, Oken MM, et al. (1995) Physician knowledge and attitudes about cancer pain management- A survey from the minnesota cancer pain project. J Pain Symptom Manage 10: 494-504.

- Levin ML, Berry JI, Leiter J (1998) Management of pain in terminally ill patients: Physician reports of knowledge, attitudes, and behavior. J Pain Symptom Manage 15: 27-40.

- Rurup ML, Borgsteede SD, van der Heide A, van der Maas PJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD (2009) Trends in the Use of Opioids at the End of Life and the Expected Effects on Hastening Death. J Pain Symptom Manage 37: 144-155.

- Rurup ML, Rhodius CA, Borgsteede SD, Boddaert MSA, Keijser AGM, et al. (2010) The use of opioids at the end of life: the knowledge level of Dutch physicians as a potential barrier to effective pain management. BMC Plliative care 9: 23-34.

- Tilden LB, Williams BR, Tucker RO, MacLennan PA,Ritchie CS (2009) Surgeons' Attitudes and Practices in the Utilization of Palliative and Supportive Care Services for Patients with a Sudden Advanced Illness. J Palliat Med 12: 1037-1042.

- Bradley EH, Cramer LD, Bogardus ST, Kasl SV, Johnson-Hurzeler R, et al. (2002) Physicians' ratings of their knowledge, attitudes, and end-of-life-care practices. Acad Med 77: 305-311.

- Maggs-Rapport F (2000) Combining methodological approaches in research: ethnography and interpretive phenomenology. J Adv Nurs 31: 219-25.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res15: 1277-1288.

- Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, Buenaventura R, Adlaka R, et al. (2008) Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician 11: S105-120.

- Swegle JM, Logemann C (2006) Management of common opioid-induced adverse effects. Am Fam Physician: 1347-1354.

- Dahan A, Aarts L, Smith TW (2010) Incidence, Reversal, and Prevention of Opioid-induced Respiratory Depression. Anesthesiology 112: 226-238.

- Hagle ME, Lehr VT, Brubakken K, Shippee A (2004) Respiratory depression in adult patients with intravenous patient-controlled analgesia. Orthop Nurs 23: 18-27; quiz 28-29.

- Fallon M (1997) Opioid rotation: does it have a role? Palliat Med 11: 177-178.

- Ward SE, Goldberg N, Miller-McCauley V, Mueller C, Nolan A, et al. (1993) Patient-related barriers to management of cancer pain. Pain 52: 319-324.

- Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D (2006) Survey of chronic pain in Europe: Prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 10: 287-333.

- Barry DT, Irwin KS, Jones ES, Becker WC, Tetrault JM, et al. (2010) Opioids, chronic pain, and addiction in primary care. J Pain 11: 1442-1450.

- Bennett DS, Carr DB (2002) Opiophobia as a barrier to the treatment of pain. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 16: 105-109.

- Su YJ, Wang CL, Ling W, Woo J, Sabrina K, et al. (2010) A survey on physician knowledge and attitudes towards clinical use of morphine for cancer pain treatment in China. Supportive Care Cancer 18: 1455-1460.

- Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Passik SD (1998) The Network Project: a multidisciplinary cancer education and training program in pain management, rehabilitation, and psychosocial issues. J Pain Symptom Manage 15: 18-26.

- Dalton JA, Blau W, Carlson J, Mann JD, Bernard S, et al. (1996) Changing the relationship among nurses' knowledge, self-reported behavior, and documented behavior in pain management: does education make a difference? J Pain Symptom Manage 12: 308-319.

- Wells M, Dryden H, Guild P, Levack P, Farrer K, et al. (2001) The knowledge and attitudes of surgical staff towards the use of opioids in cancer pain management: can the Hospital Palliative Care Team make a difference? Eur J Cancer Care 10: 201-211.