Journal of Addiction & Prevention

Download PDF

Review Article

*Address for Correspondence: Kaminer, Alcohol Research Center, at the University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT 06030-2103, E-mail: kaminer@uchc.edu

Citation: Fishman M, Kaminer Y. The Case for Placement Criteria for Adolescent Substance Use Disorders. J Addiction Prevention. 2013;1(1): 4.

Copyright © 2013 Fishman M, et al. This is an open access article distributed under theCreative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Addiction & Prevention | ISSN: 2330-2178 | Volume: 1, Issue: 1

Submission: 08 April 2013| Accepted: 12 April 2013 | Published: 13 April 2013

Unfortunately, the system and settings in which treatment for adolescents with SUD need to be provided remain difficult to access, navigate, step-up or down leading to confusion and frustration among families of adolescents in need for treatment, referral sources and providers. One of the great challenges in the field of adolescent substance abuse treatment is the attempt to assess the individual needs of drug-involved adolescents and to match them to the most appropriate treatment services, modalities and levels of care and aftercare [4,7].

The objectives of this paper are to review relevant patient treatment matching and placement criteria for adolescents with SUD. A case study will illustrate how to address these issues in the field.

Treatment matching variables that have been investigated in adults and youth include psychiatric comorbidity, motivation (i.e., timing and magnitude of readiness to change), capacity to form therapeutic alliance, differences in number, quality, and magnitude of coping-skills deficits, level of vulnerability and opportunity for exposure to different situations posing high-risk for relapse, self efficacy,negative moods, and treatment expectancies [17]. No conclusive evidence has been found to support matching hypotheses.

Substance-involved adolescents generally need an array of services broader than just “pure” substance abuse counseling alone for the multi dimensional problems they face (e.g., psychiatric, legal, family education). The debate over the chronology of SUD and comorbid psychiatric disorders is usually not as important as the need for coordination and continuity of services which even when available tend to be fragmented [8]. Other frequently needed linkages include, medical, family, special education, school support, juvenile justice, social welfare, etc. Generally, the higher the severity, the greater the need for multiple “adjunctive” services.

Another general principle of matching and placement is that increased severity and impairment requires increased intensity of services. This usually translates into an increased level of care, because lower levels of care may not be as effective [2].

Many adolescent substance abuse referral and treatment originates within the juvenile justice system. Disruptive behavior and delinquency is a very common presentation. While the common overlap with conduct disorder is a poor prognostic marker of severity [8] neither that descriptor nor associated low internal motivation or even poor cooperation, should be seen as an exclusion to treatment suitability. Rather, strategies to enhance engagement should become explicit components of treatment and placement plans.

The six ASAM PPC assessment Dimensions are listed in Table 1. Dimension 1 relates to the potential for acute and sub-acute withdrawal and intoxication and ensuing treatment needs. Dimension 2 relates to medical symptoms and co-morbidity – pre-existing, substance induced and substance exacerbated conditions, and ensuing treatment needs. Dimension 3 relates to psychiatric symptoms and co-morbidity pre-existing, substance induced and substance exacerbated conditions, and ensuing treatment needs. Dimension 4 relates to treatment engagement, motivation, resistance and stages of change. Dimension 5 relates to the likelihood of relapse, continuation of substance use and associated problems, along with potential consequences and ensuing treatment needs. Dimension 6 relates to the family, peers, living situation, and home setting.

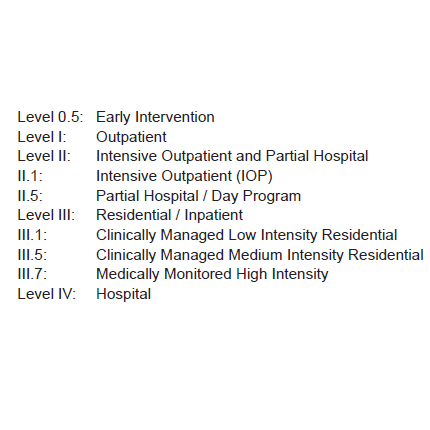

The ASAM PPC also catalogs the various common levels of care (LOCs) utilized in the treatment of adolescent substance use disorders (SUDs) as a consensus picture of the adolescent service deliverymodel. In its outline of various LOCs, as well as its descriptions of the broad range of service components that are expected in each of these individual LOCs, the PPC is a prescription for the adolescent continuum of care. The PPC LOCs are listed in Table 2. They are: early intervention, outpatient, residential, and hospital, with sub-levels within the major categories. Of course, such a prescription should not be construed rigidly, as flexibility and innovation should be encouraged to match the unique circumstances of local circumstances and even individual adolescents. Unfortunately, not all services or levels of care are available in all communities. This is particularly true of rural communities. And there are usually considerable constraints on the availability and accessibility of services in every community (for example, not enough providers, inadequate reimbursement, and too few treatment slots).

The treatment and placement matching function of the PPC operates by specifying criteria whereby increasing severity in each assessment dimension correlates to increasing service needs and thereby increasing LOC intensity for placement. In a logical sequence, severity in each assessment dimension leads to a corresponding intensity of service needs, which is in turn available in a corresponding placement. The PPC articulates the criteria that link assessment to treatment, by aggregating the array of severity in each individual assessment dimension through decision rules to produce a consolidated LOC placement recommendation.

While we work towards an expansion of the under-developed continuum, we also have to adapt realistically to the resources at hand. Often, when a given level of care is not practically available, a more intensive level of care that is available may be the best alternative. An example of this approach is the common practice in many communities of using inpatient psychiatric hospitalization (Level IV) as a setting for stabilization of substance-related crises when there is no medically monitored high intensity residential program (Level III.7) available. Another example is the use of brief residential placement (Level III.5) for daily support and monitoring when there is no partial/day program (PHP - Level II.5) available. Another adaptation to limited resources that is sometimes successful is to creatively weave together a multi-dimensional array of services from a variety of sources that approximates the intensity of the unavailable level of care. An example of this “patchwork” approach is substituting increased frequency of Level I outpatient sessions (say, 2-3 per week) for an unavailable Level II.1 intensive outpatient (IOP). Another example might be combining a Level II.5 partial hospitalization (PHP) plus an alternative, temporary living situation that is less problematic than the home environment (say, with a relative).

She lives with her grandmother. Father is incarcerated and she was removed by the protective services agency from the care of Mother, who has a history of substance abuse and a ”breakdown.” Allegation of molestation by neighbor age 9. Sexually active since 13, 8 lifetime partners, current unprotected sex with older boys, often while intoxicated. Poor school performance, repeated 3rd grade, told she was a “slow learner,” no special education services, multiple suspensions for disruptive behavior, assigned to 10th grade but truant most of year. Most friends are involved with drugs and delinquent behaviors.

Medical history notable for asthma and chronic stomach aches. Legal history notable for an arrest for possession of controlled dangerous substances on school grounds age 14, charges dropped. Received probation at age 14 for assault. House arrest age 15 for intent to distribute drugs. Most recently detained with violation of probation for theft and unauthorized use of a vehicle.

Psychiatric history notable for inattention and hyperactivity since childhood, without treatment. She has had chronic emotional lability and dysphoric mood, tantrums, explosive temper, much worse since onset of substance use past few years. Progressively oppositional and ungovernable at home. Stays away from home habitually until late and ran away overnight once. Chronic nighttime insomnia and sleeping late, with sleep-wake cycle disruption. Says marijuana helps her “chill” and avoid fights with peers. Several attempts at family and school counseling, but never sustained. No formal psych evaluation. Insomnia and irritability worse since discontinuation of marijuana use 3 weeks ago.

Assessment. Abstinent for 3 weeks, some mild “subacute” persistent abstinence effects of insomnia and irritability.

Dimension 6. (Recovery Environment).

Assessment: Grandmother is supportive but lacks the personal resources to effectively sustain treatment. Peer group is predominantly substance using.

Treatment Service Needs: Needs family intervention including training for GM on monitoring, home behavior negotiation and management, utilization of services and system (juvenile justice) leverage.

Placement: Dimensional service needs met by LeveI II.1 placement.

Integrated Multi-Dimensional Placement. The PPC contains decision rules that combine the criteria and placement recommendations for each of the individual Dimensions (as above), into an overall LOC recommendation. In this case that recommendation would be for a Level II.5 placement.

The ASAM-PPC has become the standard in the field, provides a useful guide to clinicians for placement and treatment planning, provides a framework to researchers for developing treatment matching hypotheses, and gives us a road map to advocate for greater access to needed treatment services.

The Case for Placement Criteria for Adolescent Substance Use Disorders

Fishman M1, Kaminer Y2*

- 1Assistant Professor of Psychiatry Johns Hopkins University, Medical Director of Maryland Treatment Centers, 3800 Frederick Avenue, Baltimore MD 21229

- 2Professor of Psychiatry and Pediatrics, Alcohol Research Center, at the University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT 06030-2103

*Address for Correspondence: Kaminer, Alcohol Research Center, at the University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT 06030-2103, E-mail: kaminer@uchc.edu

Citation: Fishman M, Kaminer Y. The Case for Placement Criteria for Adolescent Substance Use Disorders. J Addiction Prevention. 2013;1(1): 4.

Copyright © 2013 Fishman M, et al. This is an open access article distributed under theCreative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Addiction & Prevention | ISSN: 2330-2178 | Volume: 1, Issue: 1

Submission: 08 April 2013| Accepted: 12 April 2013 | Published: 13 April 2013

Introduction

Adolescent substance use (MTF, 2012) and substance use disorders (SUD) continue to be major public health concerns. However, SUD has unfortunately received only little resources compared to other high prevalence mental disorders in youth. Lifetime diagnoses of alcohol and drug abuse among adolescents in different states in the US range from 3–10% Seven percent of youth ages 12–17 years were classified as needing treatment for substance use disorders (SAMHSA, 2011). Due to lack of motivation, limited resources, insufficient age-appropriate quality programs, and lack of a broad consensus on preferred treatment strategies, only 10–15% of adolescents in need of treatment end up receiving service (Kaminer, 2013). In fact, youth account for a substantially disproportionate amount of the unmet national treatment need. For those who do receive any treatment, there are no good estimates of the suitability or adequacy of the type, intensity, quality or duration of those services (Fishman, 2007). Since the early 1990s there has been increased activity in the development of adolescent-specific treatment approaches (Dennis and Kaminer, 2006) as well as confirmation of short-term psychosocial treatment effectiveness of a variety of modalities with similar effectiveness [3,16]. Studies of therapy process, mediators, moderators and proximal outcomes in the treatment of addictive disorders have been developing as the new frontier in our efforts to understand mechanisms of behavior change [1,7,13]. In addition, the increasing consensus on the importance of diagnosing and treating comorbid psychiatric disorders has led to progress in research examining dual diagnosis in youth [6].Unfortunately, the system and settings in which treatment for adolescents with SUD need to be provided remain difficult to access, navigate, step-up or down leading to confusion and frustration among families of adolescents in need for treatment, referral sources and providers. One of the great challenges in the field of adolescent substance abuse treatment is the attempt to assess the individual needs of drug-involved adolescents and to match them to the most appropriate treatment services, modalities and levels of care and aftercare [4,7].

The objectives of this paper are to review relevant patient treatment matching and placement criteria for adolescents with SUD. A case study will illustrate how to address these issues in the field.

Matching Effects

Recognition of the heterogeneity of individuals with SUD led to increasing interest in the issue of patient-treatment “matching”, or the identification of variables that predict differential response to various interventions. The search for matching effects in the addiction field has amounted to the quest of the ‘Holy Grail” in terms of the magnitude, intensity, and frequency of research efforts. The largest study to date was PROJECT MATCH [10]. This was a large multi-center study on the treatment of adult alcoholics that employed different treatment modalities such as cognitive behavioral therapy(CBT), Motivational Interview (MI), and 12-step treatment strategy. However, no evidence for matching was found in PROJECT MATCH.Treatment matching variables that have been investigated in adults and youth include psychiatric comorbidity, motivation (i.e., timing and magnitude of readiness to change), capacity to form therapeutic alliance, differences in number, quality, and magnitude of coping-skills deficits, level of vulnerability and opportunity for exposure to different situations posing high-risk for relapse, self efficacy,negative moods, and treatment expectancies [17]. No conclusive evidence has been found to support matching hypotheses.

General Principles for a Successful Treatment Placement

A different focus on establishing a matching effect between individuals and clinical settings is the development of the American Society of Addiction Medicine-Placement Criteria (ASAM-PPC) for adults and adolescents. The purpose of these criteria is to enhance objective matching decisions for different severity levels to various settings of care. We aspire to a treatment system in which patients can move fluidly and flexibly up and down levels of care as needed. Often episodes of treatment at higher levels of care are (or should be) followed by longer episodes of step-down continuing care or “aftercare” [5]. Often, ongoing treatment at lower levels of care should be punctuated by periodic briefer episodes of treatment at higher levels of care in response to exacerbations known also as stepped care [15]. Repeated episodes of treatment are not necessarily an indicator of treatment failure as much as a marker of severity. Longitudinal care, rather than discrete episodes of time limited care, should be the appropriate model for a relapsing and remitting disorder such as substance abuse. Continuing care, extended monitoring phases, repeated booster doses, and in some cases indefinite maintenance treatment, should be the rule not the exception.Substance-involved adolescents generally need an array of services broader than just “pure” substance abuse counseling alone for the multi dimensional problems they face (e.g., psychiatric, legal, family education). The debate over the chronology of SUD and comorbid psychiatric disorders is usually not as important as the need for coordination and continuity of services which even when available tend to be fragmented [8]. Other frequently needed linkages include, medical, family, special education, school support, juvenile justice, social welfare, etc. Generally, the higher the severity, the greater the need for multiple “adjunctive” services.

Another general principle of matching and placement is that increased severity and impairment requires increased intensity of services. This usually translates into an increased level of care, because lower levels of care may not be as effective [2].

Many adolescent substance abuse referral and treatment originates within the juvenile justice system. Disruptive behavior and delinquency is a very common presentation. While the common overlap with conduct disorder is a poor prognostic marker of severity [8] neither that descriptor nor associated low internal motivation or even poor cooperation, should be seen as an exclusion to treatment suitability. Rather, strategies to enhance engagement should become explicit components of treatment and placement plans.

American Society of Addiction Medicine Patient Placement Criteria (ASAM PPC)

The development, refinement and implementation of standardized treatment matching guidelines have been one of the productive trends in moving the field forward. The American Society of Addiction Medicine Patient Placement Criteria 2nd Edition-Revised (ASAM PPC-2R) [11] is the guideline that has become the standard in the field, having been adopted in some form by 32 states, several managed care companies, and the military medical system. It has separate sections with distinct criteria for adults and adolescents. Its overall approach is to guide the clinician by organizing clinical data into 6 broad categories of assessment categories referred to as “Dimensions” that serve to focus the assessment on key practical domains with central treatment implications. In addition to its function as an algorithm for LOC placement, it is also a guideline for treatment matching and treatment planning in general.The six ASAM PPC assessment Dimensions are listed in Table 1. Dimension 1 relates to the potential for acute and sub-acute withdrawal and intoxication and ensuing treatment needs. Dimension 2 relates to medical symptoms and co-morbidity – pre-existing, substance induced and substance exacerbated conditions, and ensuing treatment needs. Dimension 3 relates to psychiatric symptoms and co-morbidity pre-existing, substance induced and substance exacerbated conditions, and ensuing treatment needs. Dimension 4 relates to treatment engagement, motivation, resistance and stages of change. Dimension 5 relates to the likelihood of relapse, continuation of substance use and associated problems, along with potential consequences and ensuing treatment needs. Dimension 6 relates to the family, peers, living situation, and home setting.

The ASAM PPC also catalogs the various common levels of care (LOCs) utilized in the treatment of adolescent substance use disorders (SUDs) as a consensus picture of the adolescent service deliverymodel. In its outline of various LOCs, as well as its descriptions of the broad range of service components that are expected in each of these individual LOCs, the PPC is a prescription for the adolescent continuum of care. The PPC LOCs are listed in Table 2. They are: early intervention, outpatient, residential, and hospital, with sub-levels within the major categories. Of course, such a prescription should not be construed rigidly, as flexibility and innovation should be encouraged to match the unique circumstances of local circumstances and even individual adolescents. Unfortunately, not all services or levels of care are available in all communities. This is particularly true of rural communities. And there are usually considerable constraints on the availability and accessibility of services in every community (for example, not enough providers, inadequate reimbursement, and too few treatment slots).

The treatment and placement matching function of the PPC operates by specifying criteria whereby increasing severity in each assessment dimension correlates to increasing service needs and thereby increasing LOC intensity for placement. In a logical sequence, severity in each assessment dimension leads to a corresponding intensity of service needs, which is in turn available in a corresponding placement. The PPC articulates the criteria that link assessment to treatment, by aggregating the array of severity in each individual assessment dimension through decision rules to produce a consolidated LOC placement recommendation.

While we work towards an expansion of the under-developed continuum, we also have to adapt realistically to the resources at hand. Often, when a given level of care is not practically available, a more intensive level of care that is available may be the best alternative. An example of this approach is the common practice in many communities of using inpatient psychiatric hospitalization (Level IV) as a setting for stabilization of substance-related crises when there is no medically monitored high intensity residential program (Level III.7) available. Another example is the use of brief residential placement (Level III.5) for daily support and monitoring when there is no partial/day program (PHP - Level II.5) available. Another adaptation to limited resources that is sometimes successful is to creatively weave together a multi-dimensional array of services from a variety of sources that approximates the intensity of the unavailable level of care. An example of this “patchwork” approach is substituting increased frequency of Level I outpatient sessions (say, 2-3 per week) for an unavailable Level II.1 intensive outpatient (IOP). Another example might be combining a Level II.5 partial hospitalization (PHP) plus an alternative, temporary living situation that is less problematic than the home environment (say, with a relative).

Case History

TA is a 16 girl referred from detention for evaluation. Her substance use history is notable for onset of marijuana at age 12, progressing to daily use by age 15. Alcohol onset at age 13, with weekend binges to severe intoxication. Sporadic experimentation with nasal cocaine, hallucinogens, and prescription opioids. Abstinence by confinement while in detention for the past 3 weeks. Had a few sessions of substance abuse counseling several months ago, but mostly no show because family couldn’t “make her” attend.She lives with her grandmother. Father is incarcerated and she was removed by the protective services agency from the care of Mother, who has a history of substance abuse and a ”breakdown.” Allegation of molestation by neighbor age 9. Sexually active since 13, 8 lifetime partners, current unprotected sex with older boys, often while intoxicated. Poor school performance, repeated 3rd grade, told she was a “slow learner,” no special education services, multiple suspensions for disruptive behavior, assigned to 10th grade but truant most of year. Most friends are involved with drugs and delinquent behaviors.

Medical history notable for asthma and chronic stomach aches. Legal history notable for an arrest for possession of controlled dangerous substances on school grounds age 14, charges dropped. Received probation at age 14 for assault. House arrest age 15 for intent to distribute drugs. Most recently detained with violation of probation for theft and unauthorized use of a vehicle.

Psychiatric history notable for inattention and hyperactivity since childhood, without treatment. She has had chronic emotional lability and dysphoric mood, tantrums, explosive temper, much worse since onset of substance use past few years. Progressively oppositional and ungovernable at home. Stays away from home habitually until late and ran away overnight once. Chronic nighttime insomnia and sleeping late, with sleep-wake cycle disruption. Says marijuana helps her “chill” and avoid fights with peers. Several attempts at family and school counseling, but never sustained. No formal psych evaluation. Insomnia and irritability worse since discontinuation of marijuana use 3 weeks ago.

Dimensional Assessment, Treatment Service And Placement Considerations

Dimension 1. (Intoxocation/Withdrawal)Assessment. Abstinent for 3 weeks, some mild “subacute” persistent abstinence effects of insomnia and irritability.

Treatment Service Needs. Needs education re sleep hygiene and insomnia as potential relapse trigger. Consider mild temporary sleep aid (e.g. diphenhydramine or low-dose trazodone).

Placement. Dimensional service needs met by LeveI I placement (and could be addressed in any level of care).

Dimension 2. (Medical)

Assessment: No acute problems.

Treatment Service Needs: Needs general health maintenance. Needs sexually transmitted disease (STD) screening, contraception services and sexual risk behavior counseling. At risk for exacerbation of reactive airways disease from heavy marijuana use.

Placement: Dimensional service needs met by LeveI I placement (and could be addressed in any level of care).

Dimension 3. (Emotional/Behavioral)

Assessment: Significant symptoms of affective disturbance but without evaluation or treatment. No imminent dangerousness. Social functioning significantly impaired in the school, legal and family domains. Emotional/behavioral symptoms have caused severe interference with addiction recovery efforts through lack of cooperation with treatment, deviant peer group affiliation, and self-professed psychological benefits of substance use. Impaired ability for self care characterized by ongoing sexual risk behaviors.

Treatment Service Needs: Needs psychiatric evaluation, including consideration of treatment for affective disorder. Needs programmatic treatment setting for implementation and close monitoring of psychiatric treatment (pharmacological and/or psychotherapeutic). Needs at least moderately high intensity daily structure and assessment of behavioral response.

Placement: Dimensional service needs probably met by LeveI II.5 placement with psychiatric treatment either built into the substance abuse program or provided through coordinated psychiatric services. (Consideration might reasonably be given to a Level III.5 placement, especially if additional details of assessment or lack of progress at Level II.5 suggest the need for higher intensity including 24 hr structure and boundaries unavailable in the home environment to prevent further deterioration or social functioning.)

Dimension 4 (Treatment readiness).

Assessment: Currently in pre-contemplative stage of change. Sees herself as having a probation officer problem but not a substance problem.

Treatment Service Needs: Needs significant treatment frequency, intensity and a programmatic milieu to support motivation and progression through the stages of change. Needs motivational enhancement therapy (MET) techniques including functional analysis of pros and cons of substance use, as well as juvenile justice leverage (such as probationary mandate) to improve treatment engagement.

Placement: Dimensional service needs met by LeveI II.5 placement.

Dimension 5 (Relapse/ Continued Use Potential).

Assessment: Despite brief abstinence by confinement has had no appreciable acquisition of recovery skills and remains at very high risk of immediate continued use/relapse and functional deterioration. Has not been amenable to previous Level I treatment because would not attend.

Treatment Service Needs: Needs near-daily monitoring and structure to overcome pattern of habitual use, impulsive behaviors and susceptibility to relapse triggers. Needs relapse prevention interventions including relapse trigger identification and refusal skills rehearsal, guidance in support of alternative prosocial leisure activities and peer group.

Dimension 2. (Medical)

Assessment: No acute problems.

Treatment Service Needs: Needs general health maintenance. Needs sexually transmitted disease (STD) screening, contraception services and sexual risk behavior counseling. At risk for exacerbation of reactive airways disease from heavy marijuana use.

Placement: Dimensional service needs met by LeveI I placement (and could be addressed in any level of care).

Dimension 3. (Emotional/Behavioral)

Assessment: Significant symptoms of affective disturbance but without evaluation or treatment. No imminent dangerousness. Social functioning significantly impaired in the school, legal and family domains. Emotional/behavioral symptoms have caused severe interference with addiction recovery efforts through lack of cooperation with treatment, deviant peer group affiliation, and self-professed psychological benefits of substance use. Impaired ability for self care characterized by ongoing sexual risk behaviors.

Treatment Service Needs: Needs psychiatric evaluation, including consideration of treatment for affective disorder. Needs programmatic treatment setting for implementation and close monitoring of psychiatric treatment (pharmacological and/or psychotherapeutic). Needs at least moderately high intensity daily structure and assessment of behavioral response.

Placement: Dimensional service needs probably met by LeveI II.5 placement with psychiatric treatment either built into the substance abuse program or provided through coordinated psychiatric services. (Consideration might reasonably be given to a Level III.5 placement, especially if additional details of assessment or lack of progress at Level II.5 suggest the need for higher intensity including 24 hr structure and boundaries unavailable in the home environment to prevent further deterioration or social functioning.)

Dimension 4 (Treatment readiness).

Assessment: Currently in pre-contemplative stage of change. Sees herself as having a probation officer problem but not a substance problem.

Treatment Service Needs: Needs significant treatment frequency, intensity and a programmatic milieu to support motivation and progression through the stages of change. Needs motivational enhancement therapy (MET) techniques including functional analysis of pros and cons of substance use, as well as juvenile justice leverage (such as probationary mandate) to improve treatment engagement.

Placement: Dimensional service needs met by LeveI II.5 placement.

Dimension 5 (Relapse/ Continued Use Potential).

Assessment: Despite brief abstinence by confinement has had no appreciable acquisition of recovery skills and remains at very high risk of immediate continued use/relapse and functional deterioration. Has not been amenable to previous Level I treatment because would not attend.

Treatment Service Needs: Needs near-daily monitoring and structure to overcome pattern of habitual use, impulsive behaviors and susceptibility to relapse triggers. Needs relapse prevention interventions including relapse trigger identification and refusal skills rehearsal, guidance in support of alternative prosocial leisure activities and peer group.

Placement: Dimensional service needs met by LeveI II.5 placement.

Dimension 6. (Recovery Environment).

Assessment: Grandmother is supportive but lacks the personal resources to effectively sustain treatment. Peer group is predominantly substance using.

Treatment Service Needs: Needs family intervention including training for GM on monitoring, home behavior negotiation and management, utilization of services and system (juvenile justice) leverage.

Placement: Dimensional service needs met by LeveI II.1 placement.

Integrated Multi-Dimensional Placement. The PPC contains decision rules that combine the criteria and placement recommendations for each of the individual Dimensions (as above), into an overall LOC recommendation. In this case that recommendation would be for a Level II.5 placement.

Future Directions

Matching a substance-abusing patient with the right type of treatment program is much discussed but elusive goal in the real world. Therefore, McLellan et al. [9] proposed based on a clinical trial that following a comprehensive multidimensional functional-assessment of patient’s needs, efforts should be redirected from matching patients with programs to matching patients’ problems with targeted services meeting their needs within the program. It has been recognized that a patient may not have the option of referring or switching to a more appropriate treatment program. Chances may be limited by geographical, slot availability, insurance, psychiatric comorbidity, legal status, or other considerations (Fishman 2007). This model could be tailored to be complementary or an alternative to future revised and tested American Society of Addiction Medicine Patient Placement Criteria (ASAM-PPC).The ASAM-PPC has become the standard in the field, provides a useful guide to clinicians for placement and treatment planning, provides a framework to researchers for developing treatment matching hypotheses, and gives us a road map to advocate for greater access to needed treatment services.

References

- Apodaca T (2006) The importance of studying therapy process and treatment mechanisms in addictions research. Data: The Brown University Digest of Addiction Therapy and Application 25: 8.

- Dasinger L, Shane P, Martinovich Z (2004) Assessing the effectiveness ofcommunity-based substance abuse treatment for adolescents. J Psychoactive Drugs 36: 85-94.

- Dennis ML, Godley SH, Diamond G, et al. (2004) Main findings of The Cannabis Youth Treatment randomized field experiment. J Subst Abuse Treat 27: 197-213.

- Godley S, Godley M, Dennis M (2001) Assertive aftercare protocol for adolescent substance abusers. In E. Wagner & H. Waldron (eds.) Innovations in Adolescent Substance Abuse Interventions. Oxford: Pergamon pp313-331.

- Kaminer Y (2013) Adolescent Substance Use Disorders. In: Galanter, Kleber, Brady (Eds.). The APP, Textbook of Substance Treatment, 5th Edition.

- Kaminer Y, Bukstein OG (2008) (Eds.): Adolescent Substance Abuse: Dual Diagnosis and High Risk Behaviors. Routledge/Taylor & Francis, NY.

- Kaminer Y, Godley M (2010) Adolescent Substance Use Disorders: From Assessment Reactivity to Post Treatment Aftercare: Are we there yet? Child & Adolescent Psychiat Clin N Am 19: 577-590.

- Libby AM, Riggs PD (2008) Integrated substance use and mental health services for adolescents. In Kaminer Y, Bukstein OG (Eds.): Adolescent Substance Abuse: Dual Diagnosis and High Risk Behaviors. Routledge/Taylor & Francis, NY, pp435-452.

- McLellan AT, Grissom GR, Zanis D, et al. (1997) Problem-service “matching” in addiction treatment. A prospective study in 4 programs. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54: 730-735.

- PROJECT MATCH research group (1997) Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: posttreatment drinking outcomes. J Stud Alcohol 58: 7-29.

- Mee-Lee D, Shulman GD, Fishman M, Gastfriend D (2001) (eds.) ASAM Patient placement criteria for the treatment of substance-related disorders,2nd edition-revised. (ASAM PPC-2R). American Society of Addiction Medicine, Inc., Chevy Chase, MD.

- Monitoring the Future: www.drugabuse.gov/drugpages/MTFHML (December 19, 2012). Substance Use Treatment Needs Among Adolescents. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Office of Applied Studies.

- Morgenstern J, Longabaugh R (2000) Cognitive-behavioral treatment for alcohol dependence: a review of evidence for its hypothesized mechanisms of action. Addiction 95: 1475-1490.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Office of Applied Studies: Substance Use Treatment Need Among Adolescents: (The NSDUH Report, 2010). Rockville, MD, 2011.

- Sobell MB, Sobell LC (2000) Stepped care as a heuristic approach to the treatment of alcohol problems. J Consult Clin Psychol 68: 573-579.

- Waldron HB, Turner CW (2008) Evidence-based psychological treatments for adolescent substance abuse. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 37: 238-61.

- Winters KC, Kaminer Y (2011) Adolescent behavioral change: Process and outcome. In Kaminer Y, Winters KC (Eds.). Clinical Manual of Adolescent Substance Abuse Treatment. APPI, Washington DC pp145-161.